Commentary on Isaiah 65:17-25

Two Sundays ago, the lectionary included a reading from Isaiah in which God condemns the temple worship of the elite.

Two Sundays ago, the lectionary included a reading from Isaiah in which God condemns the temple worship of the elite.

Two Sundays ago, the lectionary included a reading from Isaiah in which God condemns the temple worship of the elite.

That passage (Isaiah 1:10-18) might have given the impression that the prophets represented Israel’s “true religion,” while the temple ritual and its priestly concerns was a kind of false religion. Too often, conclusions like this can be found in the Christian tradition.

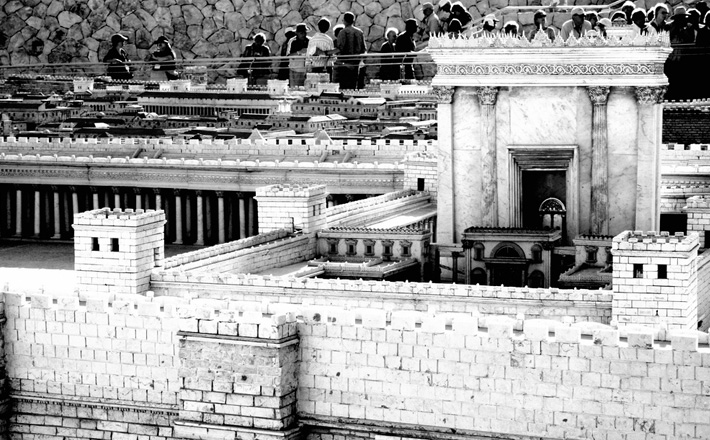

Isaiah 56-66 presents a sharp corrective to such a conclusion. These chapters, written around the time of the re-establishment of the Jerusalem temple, contain beautiful poems exalting the cosmic function of the temple. This section of the book begins with a picture of an ideal restoration, where the exclusions found in the practices of the first temple are removed so that everyone, including foreigners and those with bodily deformities can worship together. In 66:1-2, God declares that heaven is God’s throne but God’s feet rest on earth.

The passage for this Sunday may not immediately sound like a passage about the temple, but the final statement that equates Jerusalem with God’s “holy mountain” (verse 25) makes the connection explicit. This poem focuses on the city, not as the political capital, but as its religious center.

The motifs in the text are ones found in other ancient Near Eastern texts that exalted temples. Temples were viewed as the residence of the deity; in other words, built metaphors that symbolized their belief that their god was in their midst. Temple hymns viewed the earthly temple as a derivative of the deity’s true residence in heaven. Earthly and heavenly temples, then, are complementary, not oppositional. This view is found clearly in Isaiah 66.

In texts from Mesopotamia and Canann, when a deity took up residence in a temple, blessings radiated out from that temple creating an ideal world. Human endeavors were prosperous. Crops were bountiful. Animals were tame, and the world returned to an Eden-like state.

Isaiah 65:17-25 is filled with similar images. In this utopian picture infant and childhood disease, so prevalent in the ancient world, are gone. Someone who reaches a 100th birthday is considered young (verse 20). Human work is successful and fertility problems disappear (verse 23). The passage ends with echoes of Isaiah 11:6-9. Wolves stop eating lambs and the lion’s diet of straw represents its domestication (11:6-7 and 65:25). Both passages locate this picture of blessings on God’s “holy mountain” (11:9 and 65:25).

The poem also depicts this as a time of joy and rejoicing. The images cut to the heart of what touched so many lives in the ancient world. Modern readers often forget the level of poverty experienced by the ancient Israelites. For example, even in their best times, infant mortality and childhood disease were so great that only about 1 in 4 live births made it to adulthood. Women were often left infertile or even died from complications in childbirth. Today, these problems are still found in too many parts of the world, given the fact that we now have the technology to address many of these issues. For people who live in a world where childbearing is so fraught with danger, it is no wonder that paradise is a world where birthing is easy.

It is sometimes easy to think of the images contained in this passage as ancient problems. We view pregnancy as a happy time, and do not prepare the mother for the possibility of her own death. In the same way, I do not worry about being attacked by a lion when I step out my back door (although I do have a few aggressive squirrels to contend with). As a result, too many times when I go to church, I am not expecting the world to change into a paradise.

The poem points to the reality behind worship, and creates a picture of what that virtual world looks like. God creates a new reality; the participial form of the verb in verse 17 here suggests creation is God’s on-going activity. That ideal world is being created “new” every day. God’s creative work turns the profane world of the city into holy space, God’s territory. Divine blessings radiate out into the steppe and the wilderness, the abode of wild and dangerous creatures. Every day, God recreates this cosmos: a world of harmony, prosperity and joy.

In today’s world, this is sometimes replaced by the “prosperity gospel,” the notion that if we praise God and do the right things, God will reward us individually with prosperity. Too often, though, we think “prosperity” means money and, personal wealth for us as individuals.

The picture of prosperity in Isaiah is not one of personal wealth. It is a picture of communal harmony. And that community is defined in the broadest of terms: it includes even the things that can harm us. The blessings are not demonstrated by the wealth of the elite: there is no prosperous king in this picture. God’s blessings are seen when the poorest and most at risk among us live to a ripe old age.

Isaiah 65:17-25 invites people today to consider how our experience of God’s holiness changes the world for us. We may not feel a great need to domesticate lions, but what would the world look like if children did not die from disease or gun violence, if adults had complete access to the best medical care, and if everyone earned a livable wage so that their work was not in vain. What if everyone could have as many children as they wanted, knowing they could provide for them without anxiety? Isaiah tells us that this is the world that worship should invite us to imagine.

November 17, 2013