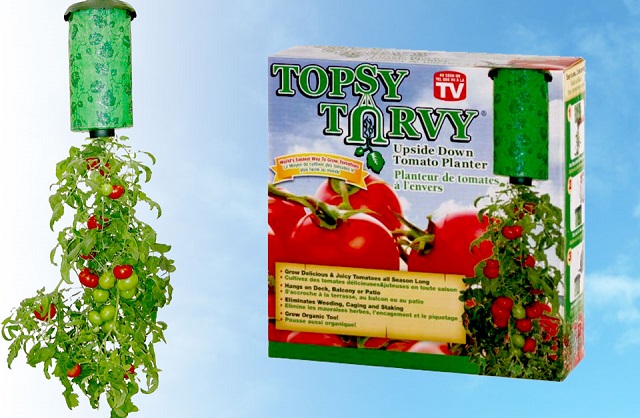

Those of us who stay up late watching “As Seen on TV” ads may remember seeing the Topsy Turvy upside-down tomato planter. This product allows apartment dwellers and other people who don’t have (or don’t want to maintain) conventional garden spaces to hang a tomato plant and watch it spread and grow from the top down, rather than the traditional bottom-up way. According to the ad, it’s easy to pluck the ripe tomatoes without having to weed, prop up or cage the plants.

This week’s Gospel lesson shares passing similarity with the Topsy Turvy tomato planter. In it, Jesus overturns conventional notions of what it means to be a messiah, especially what a messiah should do, what checkboxes he should tick off, and how exactly that messiah will bear fruit come harvest time.

The flip—or inversion, if you will—starts earlier in Matthew’s Gospel. This week’s text (Matthew 17:1-9) marks the conclusion of a larger section focused on the identity of Jesus and the nature of his ministry. Quite appropriately, the literary unit begins with the question: “Who do you say I am?” (Matthew 16:15). This question reverberates throughout the subsequent narratives all the way to the Mount of Transfiguration (Matthew 16:13-20, 21-23, 24-28, and 17:1-13).

These narratives—focused as they are on revealing Jesus’ identity as messiah—are full of confusion and misunderstanding. Jesus’ ministry doesn’t make sense, either to the disciples or the teachers of the law. His ministry is easy to misunderstand and easy to oppose.

Before commenting directly on the Transfiguration text, let’s revisit the preceding material. Beginning at Matthew 16:13-16, a sequence of revelations unfolds about Jesus’ messiahship. In Matthew 16, Jesus asks his disciples who the Son of Man is. Peter answers, “You are the Messiah, the Son of the living God” (Matthew 16:16). Despite Peter’s own clarity about Jesus’ ministry, controversy and speculation ran wild among the larger public, so much so that the people of Jesus’ time assumed he was a prophet of old, somehow returned from the dead. This exchange is followed by a promise regarding the church’s call in the current messianic age and—spoiler alert!—the fact that Jesus’ ministry will ultimately end in suffering.

Reading Matthew 16:18-19 on their own (“I will give you the keys of the kingdom of heaven; whatever you bind…”), one could easily assume that the church would simply steamroll every demonic obstacle in its path. But the Gospel of Matthew is more sophisticated than that. The church is given the gift of victory over the power of Hades. But that victory issues forth from Jesus’ death on the cross. The hordes of Hades will succeed in killing the messiah. But that “victory” contains within it the seeds of Hades’ downfall.

The text takes a significant turn at this point. Peter demonstrates that his understanding of Jesus’ ministry remains deeply flawed. Peter chides Jesus, stating that “This [crucifixion] shall never happen to you.” For Peter, Jesus could not be both the Messiah and a victim; these two ideas are mutually exclusive. Jesus confronts Peter in the same way he confronts demons: with a forceful rebuke (Matthew 16:22-23). Like so many of us, Peter associated Jesus’ ministry with glory and victory, not suffering and defeat.

It may be that Peter’s protest also betrays his self-interest. Peter may have assumed what Jesus now makes plain—that the cruciform call of the master is also the call of the disciples: “If anyone would come after me, let him deny himself and take up his cross and follow me. For whoever would save his life will lose it, but whoever loses his life for my sake will find it” (Matthew 16:24-25). This call to “take up” the cross is followed by a description of Jesus’ own glorious coming: “For the Son of Man is going to come in his Father’s glory with his angels, and then he will reward each person according to what they have done” (Matthew 16:27).

Once again, Jesus interweaves the cross and glory, and in the process transforms the meaning of both.

And now the stage is set for this week’s Gospel. Matthew 17:1-9 offers a similarly difficult pill to swallow. Like the other stories in this unit, these verses redefine divine glory in light of the cross, showing that Jesus’ suffering is integral to his messianic ministry. What’s different, though, is that the glory of God is not something promised, as in Matthew 16:27; rather, it shows up in real time, before Peter, James, and John. And in a clear echo of Moses’ own encounter with glory in Exodus 34:29-35, Jesus is transfigured before them (Matthew 17:2).

Appearing with Jesus are Moses and Elijah, representing Israel’s legal and prophetic traditions. A voice interrupts the scene with an announcement: “This is my son, whom I love; with him I am well pleased. Listen to him!” (NIV; see also Matthew 3:17). Jesus is singled out among the three men as the one whose voice should be heeded. The point is not that Jesus’ teaching now replaces that of Moses and Elijah. Jesus stands in complete continuity with them, as the Gospel made clear in an earlier chapter (“Do not think that I have come to abolish the Law or the Prophets; I have not come to abolish them but to fulfill them,” [Matthew 5:17]). Jesus, rather, is to be the chief interpreter of these traditions and the chief expression of their hopes.

If you read beyond verse 9 in this week’s passage, you find Jesus again raising the matter of his future suffering:

“But I tell you that Elijah has already come, and they did not recognize him, but did to him whatever they pleased. So also the Son of Man will certainly suffer at their hands.” Then the disciples understood that he was speaking to them of John the Baptist (Matthew 17:12-13).

Like John the Baptist, Jesus’ call was not recognized by the people of his time. Even those charged with the study of Scripture could not properly understand Jesus’ ministry. His glory was hidden, and as he continued his journey to the cross it will become even more so.

Like the disciples, we are easily confused about Jesus’ ministry. This is all the more true in our current culture, which is obsessed with winning and “crushing it.” This mindset, which dominates many aspects of our culture (you fill in the blanks with your favorite examples), has the potential to corrupt how we think about the ministry of Jesus in our congregations and communities today. Jesus’ glory is most apparent when the darkness dominates (Matthew 27:45-54).

Truth is, the glorious ministry of the Messiah is with us every day—in every congregation, every funeral, and every agonizing sermon-writing session. Jesus’ glory is not there to terrify (Matthew 17:6-7), but rather, like the heavenly voice, to point us to the paradoxical glory of the crucified Messiah.

This type of messiahship is not convenient, nor is it even practical, like the Topsy Turvy tomato planter. But once the flip has been made—from expecting a Messiah of glory to welcoming a Messiah who is poured out for us and transforms us—it’s hard to go back to the conventional way of planting.