Haywire, directed by Steven Soderbergh, boasted everything I want in a movie: an acclaimed director, a blockbuster cast, and an intriguing plot.

Sadly, this is not a particularly good story (notice that I said story not movie). It’s not that the story is bad, in fact the plot concept is very, very good; rather, it’s that the story has been told so many different times that its overuse frustrates its intrigue. The storyline is well-known to action movie addicts such as myself: a secret agent is framed by a yet-to-be-determined enemy with seemingly limitless resources and she must fight her way through a frenetic twist of events to clear her good name. Been there; seen that.

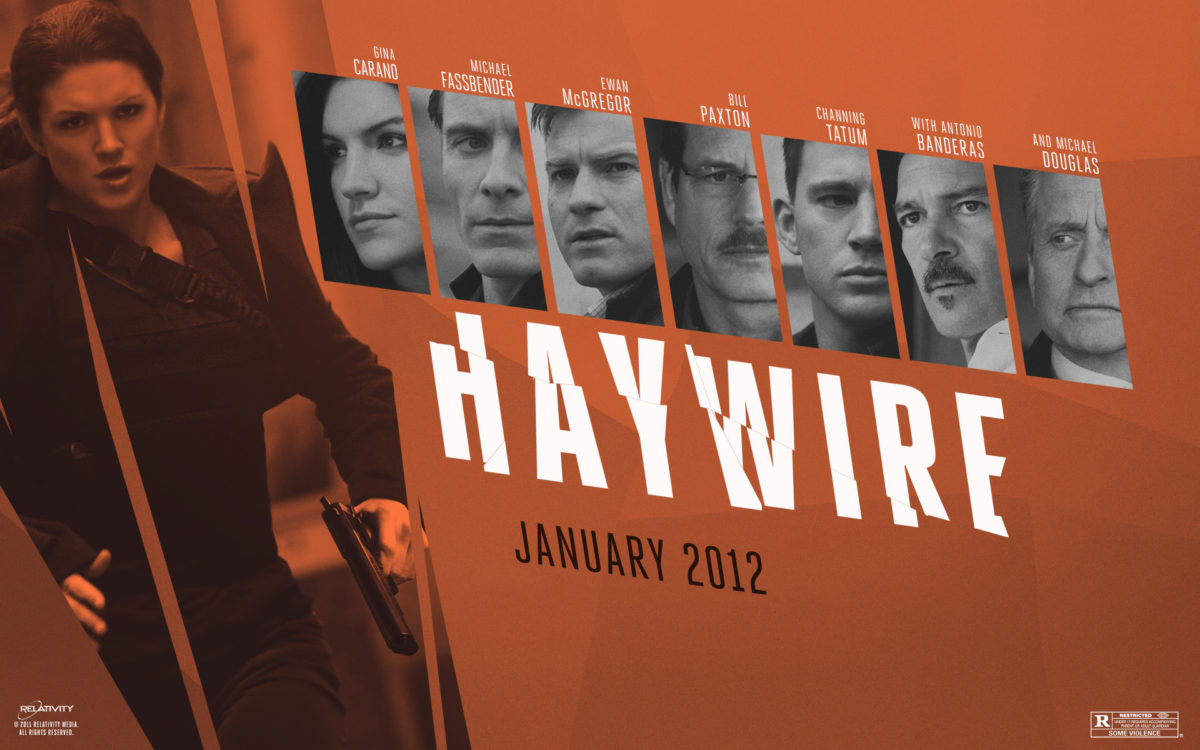

As a movie, Haywire does have several redeeming qualities. First, the film benefits greatly from an overwhelming array of eye-candy. Everyone is beautiful in this movie, and this feature keeps us watching as stars like Ewan McGregor, Channing Tatum, Michael Fassbender, Antonio Banderas, Michael Douglass, and the star of the film, mixed martial art sensation, Gina Carano, grace the screen.

Second, the hackneyed narrative arch is ameliorated by tightly choreographed fight sequences that are arrestingly realistic. Never before have I seen a woman fight a man in a movie with the same ferocity and precision as Carano. The willing suspension of disbelief is unnecessary when you watch Carano’s spellbinding display of fisticuffs. No CGI or slow-motion shenanigans are needed to convince you that Gina Carano could really, really hurt you if she wanted to.

In spite of its narrative flaws, Haywire is a must-see movie for preachers. We can learn much from the way in which Soderbergh tells this story through his singularly gifted display of directing. As preachers, our lot is not far removed from Soderbergh’s: how do we tell the same story over again in a different way that allows the force of the story to arrest our audience’s attention?

Some time ago, Thomas G. Long taught us about the relationship between a story’s form and its content. Recall that he encouraged us to allow “the force of a biblical text to be expressed through a sermon form” and that “the preacher’s task is not to replicate the biblical text but to regenerate the impact of some portion of the text.” Thus, our task is not altogether different from a director’s. Taking Long’s sage advice to heart, Haywire offers we who preach a fresh perspective on the craft of preaching.

There are several points you will want to observe as you watch this film. (Please note that I am not suggesting that we “do” these things; rather, I believe that these points of analysis can help us to think about the form of our sermons in fresh ways.)

Pacing

Pay attention to the pacing of the film, and especially the transitions. Even as the plotline leads the main character along a string of events that have gone haywire, the way in which the narrative unfolds is anything but. Soderbergh reveals a level of narrative sophistication that draws together the erratic turn of events in the character’s life to craft a tightly woven story. In short, he creates order out of chaos. Think about how this display of pacing might inform our pacing in sermons, particularly through our use of sermonic transitions.

Cinematography

Soderbergh is unique among directors in that he elects to do much of the filming himself, thereby allowing him to get just the right shot for each scene. Through an eclectic array of camera angles, the occasional use of monochromatic light filters, and visually stimulating depth of field shots, Soderbergh presents us with a stylish, visual smorgasbord. A clear example of this is found in a hostage recovery scene set in Barcelona. The scene is familiar. The “good guys” must storm a room occupied by the “bad guys” to rescue a defenseless hostage. How many times have we seen this portrayed in films? In Haywire, neither the rescue itself nor the facility of the rescuers is particularly noteworthy. They blow the door, storm the room, rescue the hostage. However, when one considers the style with which Soderbergh renders this scene, the result is enrapturing. What happens to our preaching when we shift our angle of vision to tell the story from different perspectives?

Music

If you have seen any of Soderbergh’s films in the Ocean’s Eleven franchise, you will likely recall the way in which music enhances the visual cornucopia on screen. Haywire continues in this trajectory with Soderbergh employing a jazzy mix of beats to accompanying his suave display of storytelling. Few traditions employ music to accompany the sermon (and perhaps this is something we should re-think within the context of our own ecclesial traditions); nevertheless, the melodic flow of Haywire can help us think about the oral/aural dimensions of our preaching that might enhance the force of our sermon. Our voice is our homiletical instrument and Soderbergh’s aural panache can show us a thing or two about how we employ sounds in our sermons.

With Haywire, seldom has a bad story been told so well. Imagine what can happen to our preaching if we glean some narrative insights to tell a good story even better.

1 Thomas G. Long, Preaching and the Literary Forms of the Bible (Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1988), 128, 127.