Commentary on John 1:6-8, 19-28

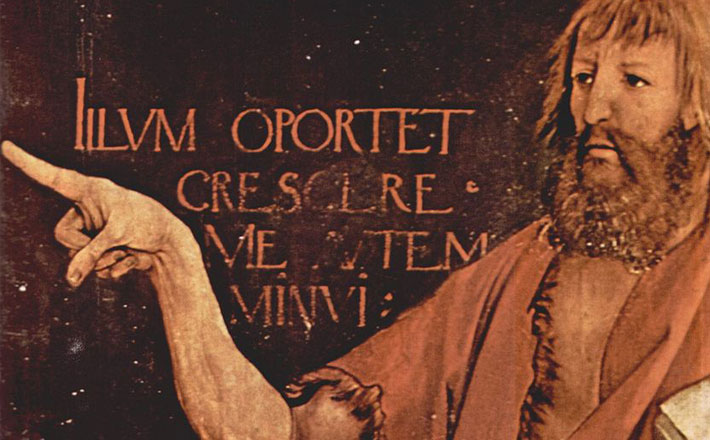

Grunewald’s Isenheim Altarpiece is one of the most famous religious artworks of all time.

Even if you are not an aficionado of Renaissance/Reformation era art, you have probably seen this piece (and you can certainly find it on the Internet).

The center panel offers a tortured and gruesome portrayal of Jesus on the cross, suffering with an agony painful to behold. But immediately to the right, standing off to the side is John the Baptist, holding open a copy of the scriptures and pointing knowingly to the figure on the cross. At John’s feet is a small lamb.

Grunewald would not have been a good redaction critic. Like most people today, he got his Gospels mixed up. The portrait of Jesus comes straight from the Gospel of Mark, where the passion narrative emphasizes the terrible suffering of Jesus rather than the great victory his death accomplishes. But if Grunewald gives us a Markan Jesus, his figure of John the Baptist is Johannine all the way. In John’s Gospel, that’s what John the Baptist does: he points to Jesus.

In the Synoptic Gospels, John the Baptist is a prophet who has an important ministry in his own right. He calls people to repentance and eventually dies as a martyr for daring to confront petty earthly tyrants with the word of the Lord. But in John, for the most part, he just points people to Jesus.

The text for today tells us more about who John wasn’t than about who he was: he wasn’t the light; he wasn’t the Messiah; he wasn’t Elijah; he wasn’t the prophet.” Who, then, was he? He was a witness (John 1:7) and he was a voice (John 1:23), albeit a voice telling people to prepare for someone else, someone whose sandal thong John was unworthy to untie (John 1:28).

There are probably historical reasons for this subordination. Many of the commentaries discuss various versions of a theory that John’s significance had to be downplayed in some segments of the church because his followers had become competitors with the followers of Jesus. Thus, John himself is represented as directing his followers to Jesus and as declaring that “he must increase, but I must decrease” (John 3:30).

Whatever political struggles might have influenced the Fourth Gospel’s presentation of events, the account we have before us offers a different nuance than what we encountered in Mark. If your sermon last week focused on the content of John’s message, you might focus this week on the style. That is what seems most important to the writer of our Fourth Gospel: it is not just what he says about Jesus that is important, but how he says it.

John is a witness (martyría; John 1:7) who testifies (martyréo; John 1:7, 19) to the good news of Jesus Christ. Those two words are used more than forty-five times in John’s Gospel and are expressive of what many consider to be a central theme of the work. They have their origin in a legal context and, so, imply public testimony to something that one guarantees is absolutely true.

When a witness testifies to something, he or she stakes his or her life on it; a “false witness” commits perjury, a capital offense. This, of course, explains the origin of our English word martyr: a witness who suffers the ultimate consequence when his or her public testimony is deemed false. John is only the first of many to testify on behalf of Jesus in this Gospel (see, e.g., John 4:39; 5:36, 37, 39; 12:17; 15:26, 27).

Like the man whose name was John, the church is sent into today’s world as a witness. So, focusing specifically on the text for Advent 3, we may characterize this witness as public, certain, and humble.

These qualities are in tension with the spirit of our age. Most people today regard religion as a private matter and do not want to hear about someone else’s particular beliefs. Certainty is also shunned in these postmodern times; we are all victims of our own perspectives: who can ever know for sure whether anything is true or not?

Still, we are audacious enough to believe that the gospel is true, and that it must be proclaimed boldly — publicly and confidently.

The trick is to bear witness to this truth with humility. For John, that meant directing people away from himself and toward Jesus. Notice how people try not to let him do that. “Who are you? What do you say about yourself?” (John 1:22).

That is one thing that has not changed. Talk about Jesus, and people will always want to change the subject; often they want us to talk about ourselves. And frequently that may be what we would prefer to talk about as well.

Don’t take that bait. Our testimony about Jesus is ultimately less significant than Jesus’ testimony about us. Sure, share your opinions and beliefs about Jesus with friends, neighbors, and strangers (if they’ll listen), but that’s all you’ve got, beliefs and opinions.

The testimony of Jesus himself is more powerful. His words are the word of God; his actions, an incarnation of that word, putting us all on trial with public testimony. The light of God’s love and the darkest parts of humanity come together, and there need be no postmodern squabbling over what happens when darkness and light try to co-exist: the truth of what happens is public and certain.

December 14, 2014