Some preachers avoid the e-word while others do not, yet we are all evangelists.

We all long to proclaim Jesus in the most appealing terms possible. Few messages appeal more than the inclusive Jesus, the one who liberated a Gentile’s daughter, celebrated a centurion’s faith, chit-chatted theology with a Samaritan woman, and apparently relished disreputable company.

On Christmas Eve the New York Times published a meditation, “The Forgotten Radicalism of Jesus Christ” by Peter Wehner. Lots of my preacher friends shared it on social media. A noted political commentator and evangelical Christian, Wehner critiques contemporary Christians for forgetting the “hallmark of Jesus’s ministry, intimacy with and the inclusion of the unwanted and the outcast, men and women living in the shadow of society, more likely to be dismissed than noticed, more likely to be mocked than revered.” By substituting a respectable and spiritual Jesus in place of the one who rubbed elbows with prostitutes, Christians corrupt the church and forfeit the blessing of human encounter. Wehner’s piece reminds me how essential it is to proclaim the welcoming Jesus. Its limitations foreground the importance of how we preachers do so.

We all know large sectors of the church are experiencing dramatic decline. This is especially true in historically White churches. Few of us trust surveys these days, but the pollsters and sociologists tell us that this decline is largely due to several consistent factors: many people regard the church as largely irrelevant, too moralistic and judgmental, and too heavily politicized. Preaching an inclusive Jesus speaks directly to these complaints.

I suspect, however, that it’s not enough simply to celebrate Jesus’s radical inclusion. Somehow our proclamation must empower hearers to imagine themselves living into the same life. Wise preachers never talk down to people, guilting them into broadening their range of contacts. The kind of preaching works only briefly, if at all. Nor do we need grand illustrations, stories of spiritual heroes who bring their all their rowdy friends into the circle of faith.

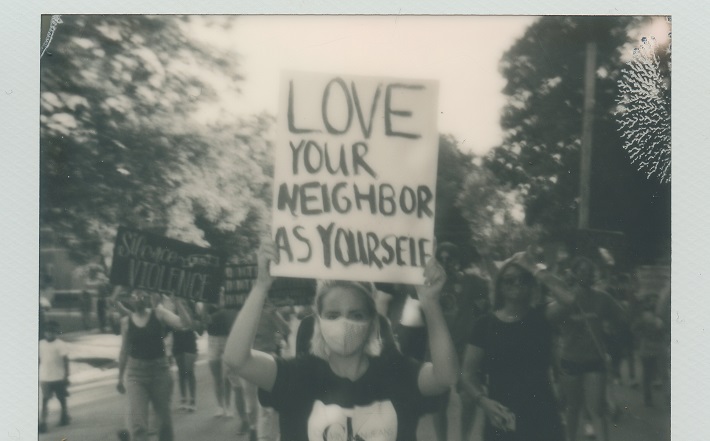

We need preaching that empowers us as disciples who live into a gospel that unites us with all our neighbors. We need preaching that pulls and pushes us into Jesus’s wondrous story.

Faithful preachers will reject the familiar trope that pits Jesus against the “cultural environment” of his day. I call this preaching by comparison: “Jesus’ contemporaries were bad, but Jesus was terrific.” Generations have preached that Jesus welcomed all kinds of people, while his culture excluded lepers, bleeding women, women in general, Gentiles, and sinners. That preaching model is straight-up irresponsible, and on several levels.

First, preaching by comparison has a long association with anti-Judaism and anti-Semitism. By “Jesus’ contemporaries,” preachers typically point to ancient Judaism or to key groups like Pharisees and priests as setting up boundaries that oppress certain categories of people. It’s still common for Christians to imagine that Judaism lacks grace and divides people from one another, or that it did in Jesus’ day, while Jesus breaks through those boundaries. As a seminary professor I encounter this bias in students every year.

The argument that Judaism lacks grace amounts to slander. It’s also bad history. The God of Israel is slow to anger and abounding in steadfast love (Exodus 34:6; Numbers 14:8; Nehemiah 9:17); God’s mercies are new every morning (Lamentations 3:23); God removes our sins as far as the east is from the west (Psalm 103:12). The rabbis frequently acknowledged that God forgives sins out of an abundance of mercy. If Jesus practiced grace and mercy, those things came naturally to him as a child of Israel.

Second, preaching by comparison is unnecessary. Does it not seem strange that some preachers need to make someone look bad in order to make Jesus look good? Is not Jesus wonderful enough in his own right? It’s bad theology and lazy preaching, to magnify Jesus by comparison.

But there are better ways. Preachers might begin by noticing the reactions to Jesus’ ministry. Yes, the Gospels describe conflict with Pharisees and other groups. But look at the people on the scene, all of them fellow Jews. No one protests, “He can’t touch a leper!”, or, “What’s he doing talking to that woman?” “They were all amazed and glorified God” (Mark 2:12). “They were overcome with amazement” (Mark 5:42).

It’s not always that way. Every once in a while a crowd complains about the company Jesus keeps (Luke 19:7); even so, it appears the tax collectors and other sinners know they have a welcome from Jesus (Luke 15:1). Apparently most people rejoice to see their neighbors delivered from affliction. Generally speaking, people marvel at these encounters, crowds flocking to Jesus because he heals all classes of people.

We preachers tend to focus on Jesus, but an alternative strategy lies close at hand. Remarkably, the Gospel authors often place the spotlight on the people Jesus encounters. They generally initiate their encounters with Jesus, not the other way around. A leper kneels in front of Jesus to seek his cleansing. The paralytic’s friends tear through someone’s roof. A father begs repeatedly that Jesus would heal his daughter, while a hemorrhaging woman sneaks up to touch Jesus’s garments. A Syrophoenician woman implores the resistant Jesus to cast out the demon who torments her daughter.

In all these cases, so often cited as examples of Jesus’ inclusivity, Jesus is not the one who crosses the boundaries. We might even ponder what mission would look like if it begins not with the church’s agenda but with our neighbors’ present needs.

Once we move beyond comparison, we preachers are free to marvel at the ways in which people respond to Jesus. They praise God because of his healing power. Whatever their status or affliction, they track him down to encounter that power. I would suggest that wonder and passion present more appropriate responses to the stories of healing and inclusion, as the Gospels elevate these values above others.

For preachers seeking greater understanding of Jesus’s ministry within the context of Judaism, I recommend the following books.

- Amy-Jill Levine, The Misunderstood Jew: The Church and the Scandal of the Jewish Jesus. (New York: HarperOne, 2006).

- Matthew Thiessen, Jesus and the Forces of Death: The Gospels’ Portrayal of Ritual Impurity within First-Century Judaism. (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2020).

For alternative readings of Jesus’s interactions with lepers, sinners, the hemorrhaging woman, the dead child, and Gentiles, consider this book.

- Greg Carey, Sinners: Jesus and His Earliest Followers. (Waco: Baylor University Press, 2009).