Commentary on Jeremiah 23:1-6

In a presidential election year, politics take center stage in the United States.

Before, during and even after the day itself, there is divisiveness: Which side is correct? Does a “lesser of two evils” exist? Will the leader who is selected take the country in the right direction — politically, economically, ideologically, morally? If you have found yourself lamenting your choice in national leaders (as a general rule or more specifically in this particular political era), rest assured that you join a long tradition of such lament. For example, Jeremiah 23:1-6, is set within the larger pericope of chapters 21-23, which focus on the fall of Jerusalem to the Babylonians in 587 bce. In particular, these three chapters emphasize that the various institutional and national leaders of the time — especially the kings, the priests, and the prophets — failed the people of Judah during a time of catastrophic national crisis.

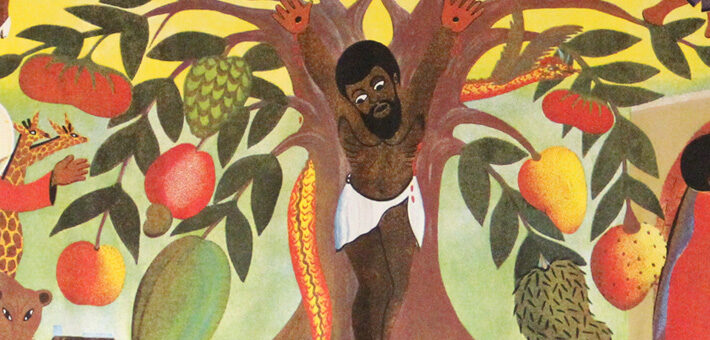

Our passage begins with a woe oracle: “Woe (Hebrew: hoy) to the shepherds who destroy and scatter the sheep of my pasture!” (Jeremiah 23:1). Blame clearly rests here on the shepherds, a well-known metaphor for kings in both the larger ancient Near Eastern world and in the biblical texts (see, for example, 2 Samuel 5:2; Isaiah 44:28; Jeremiah 3:15). These verses anticipate the exile of 587 bce, blaming the kings for “scattering” Yhwh’s people because the kings-as-shepherds failed to attend (Hebrew: pqd) to the people-as-sheep. As indicated by the New Revised Standard Version translation, the divine indictment that follows includes a word play: because the kings failed to attend (pqd), in other words, to take care of the people as shepherds are meant to take care of their flocks, Yhwh promises to “attend” (pqd) to the kings for their “evil doings.” The calamitous predicament that these kings find themselves cannot be overstated, for the Hebrew hoy derives from lament language used by mourners over the dead.1 As David Petersen aptly summarizes, “If an oracle began with a woe, then the prophet seemed to be saying that someone or some group was as good as dead.”2 In our case, the kings have failed in the eyes of Yhwh.

Yet while our passage begins with pessimism and an ominous indictment for the shepherds, it moves forward with hope for the sheep. Yhwh promises “I myself will gather the remnant of my flock out of all the lands where I have driven them, and I will bring them back to their fold, and they shall be fruitful and multiply” (Jeremiah 23:3). Note here that only a “remnant” of the flock remains, another indication of how badly the shepherds have been tending their flock. (Readers will also note a tension here, for while in the previous verses the scattering of the sheep was because of the errant shepherds, here in v. 3 Yhwh notes that he will bring the sheep “out of all the lands where I have driven them.” The exile is at once both caused by the behavior of the kings and also by the agency of the Shepherd of the shepherds: Yhwh.)

As scholars frequently note, once the “remnant” is returned home to the land, the passage invokes the language of Genesis and the promises to the ancestors: the people shall be “fruitful and multiply.” These verses promise rescue and deliverance, a prosperous future for the people, even as Yhwh “attends” to the kings in judgment. Moreover, these verses promise that God will act without any intercessor — without king or priest or prophet — to bring the remaining sheep out of exile.

Therefore, it is somewhat of a surprise when Jeremiah 23:4 looks forward to the restoration of the monarchy, as Yhwh promises to “raise up shepherds” over the returned exiles (23:4). Unlike the previous shepherds, however, these kings will take care of the people, who “shall not fear any longer, or be dismayed, nor shall any be missing” (23:4). This promise of a restored monarchy, while hopeful, is also unexpected set within the larger pericope of Jeremiah 21-23, which so adamantly distrusts and lambasts the ruling institutions of the day, especially the kings. So there is yet another tension in the text: Yhwh both acts without a human agent for the scattered remnant, bringing them home, but also promises a future where there will be a new human king to rule over and protect the people. Jeremiah 23:1-4 is both negative and positive, both sentence and deliverance.

Despite this, the passage ends with unfettered hope. The two final verses of the pericope look forward not only to a restored monarchy, but also to a very specific kind of king: “The days are surely coming, says the LORD, when I will raise up for David a righteous Branch, and he shall reign as king and deal wisely, and shall execute justice and righteousness in the land. In his days Judah will be saved and Israel will live in safety. And this is the name by which he will be called: ‘The LORD is our righteousness’” (Jeremiah 21:5-6). Several notable features stand out about this promised king: 1) he will be heir to the divine promise to King David; 2) he will be wise and will “execute justice and righteousness in the land” (rather than failing to attend to sheep so that only a remnant remain as with the previous shepherds); 3) he will protect and rule both Judah and Israel; 4) and he will be called yhwh s?id_qenu, “Yhwh is our righteousness.”

As is often observed, the name is similar to that of Zedekiah (“My righteousness is Yhwh”), the last king of Judah who ruled from ca. 597-587 BCE and who was appointed by King Nebuchadrezzar but eventually rebelled against Babylon, despite Jeremiah’s warning that he should not do so (see 2 Kings 24:19-25:21; Jeremiah 21:1-10). Where Zedekiah failed, this Jeremianic passage looks forward to a future Davidic king who will actually be righteous, wise, and just IN short, everything that Zedekiah proved not to be. Moreover, this new Davidic king will rightly acknowledge that Yhwh is the righteous and real king of Israel: “Yhwh is our righteousness.”

While later interpreters will see in this Jeremianic passage a prediction of Jesus Christ as the “righteous branch,” we as readers must also remember that long before the biblical texts of the prophets became religious documents for the early Christians, they were first political documents that reflected the historical realities and concerns of their authors. For the author of our passage in Jeremiah 21:1-6, the kings had failed the people. Nevertheless, there was still hope for a future, legitimate monarch who would restore righteousness and, as shepherds were meant to do, protect the people from threats both external and internal.

Of course, even with the hopeful promise of a future and ideal Davidic king, it is helpful to pause and remember the larger unit of Jeremiah 21-23. Earlier, when Jeremiah counseled King Zedekiah to leave Jerusalem to the Babylonians, he spoke to the people — the sheep — and said, “Thus says the LORD: See, I am setting before you the way of life and the way of death. Those who stay in this city shall die by the sword, by famine, and by pestilence; but those who go out and surrender to the Chaldeans who are besieging you shall live and shall have their lives as a prize of war” (Jeremiah 21:8-9). Jeremiah’s early words are an important reminder that while leaders — divinely appointed or not — serve an instrumental role in their countries, the people, too, have responsibility and choice.

While our passage opens with judgment and closes with a promise of a future leader who will save and protect the people, the larger book of Jeremiah does not let us — the people — off the hook as we wait. We too must choose. Our choices might not be as dire as “the way of life and the way of death,” but they are nevertheless significant and can affect both those near to us and those a world away. While we live in a world where we often want to place the blame for societal ills on political leaders or larger institutions, our choices — political, economic, ideological, ecological, and more — matter. Our voices, as people, count, as does our engagement or lack of engagement with the world around us. And so while we might hope that our political leaders will “execute justice and righteousness,” in the here and now we make choices and we act — and the choices we make impact whether justice and righteousness are found in the world around us.

Notes:

1 David L. Petersen, The Prophetic Literature: An Introduction (Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press, 2002), 67.

2 Ibid.

November 20, 2016