Commentary on Luke 22:14—23:56

“Which is more amazing,” asks Karl Barth, “to find Jesus in such bad company, or to find the criminals in such good company?”1

[Preaching on the Procession of Palms text? See this commentary on Luke 19 by Michael Joseph Brown.]

So Barth began his Good Friday sermon on Luke’s account of the two criminals with whom Jesus was crucified. Preached for the inmates of the Prison of Basel in 1957, Barth’s sermon proves tantalizing as well as instructive even now, nearly sixty years on.

Interpreters will find the sheer expanse of the text assigned for Passion Sunday challenging. How to begin? For his sermon, Barth focused on Luke 23:39-43, the unlikely community of the crucified. With that image firmly in mind, he cast his sermonic eye over the larger narrative, particularly Luke’s account of the Lord’s Supper in 22:14-23 as well as the contrast between the “indissoluble” community of criminals and the “vacillating” community of disciples. While you may choose a different image, the strategy used by Barth commends itself.

This text begs for a theological reading and Barth does not disappoint. Barth’s sermon delves into themes of solidarity between Jesus and the criminals, but it does not stop there. He describes Jesus’ suffering as the visible sign of God’s invisible grace. Although it seems impossible on the surface that Jesus’ betrayal, suffering, and death could “accomplish” anything good, Barth insists that where humankind intended evil, God produced the good.2

However “distant” our experience of God’s work of reconciliation, Luke testifies that in Christ’s suffering, God’s kingdom has drawn near.

As evidence, consider the paradox of distance and nearness in this text and beyond. Luke plays with the irony of those who are “close” to Jesus (even “laying hands” on him) and yet remain indescribably far from him. A few examples …

• Jesus immerses himself in prayer while the disciples, who are just a “stone’s throw” distant, are overcome with grief and go to sleep (22:45); • Judas betrays Jesus with a kiss, the kinship of the kiss eclipsed by the enormity of the betrayal (47b); • Not only does Peter reverse his confession of 9:20, his three-fold denial, “I do not know him!” (57b), amplifies the physical distance he keeps from Jesus in the courtyard outside the high priest’s house where Jesus is being interrogated (22:54); • Likewise, the Roman soldiers deride Jesus: “Prophesy! Who slapped you in the face?” (64b). What might have been prayer, turns into mocking abuse; those who might have worshipped God, instead abused him. |

In each case, the distance seems irrevocable and yet, curiously, Luke insists that Jesus remains radically present to those who would betray, deny, or cast derision upon him.

With the criminals, Jesus’ nearness takes on the form of solidarity in suffering, according to Barth. But something greater than solidarity is at stake: “We do well to remember that this [reconciliation] is what those who put him to death really accomplished. They did not know what they did.”3 They may not have known, but in Barth’s theology, Christ, God’s Son, surely knew.

Moreover, Jesus’ proximity to suffering is hardly benign or passive. What Barth says of the two criminals that were crucified with Jesus, we might extend to each of the characters in this text: “Nor could they escape his dangerous company.”4

In Luke’s account, distance does not mitigate or otherwise diminish the dangerous company of Christ.

In this connection, Fred Craddock describes three responses to the “spectacle” (Luke 23:48b) of Jesus’ death in verses 45-49: (a) in the person of the Roman soldier (47); (b) the crowds who returned home “beating their breasts” (48); (c) and in Jesus’ “acquaintances, including the women who had followed him from Galilee” who “stood at a distance, watching these things” (49).5

Craddock recalls earlier uses of this expression at Luke 16:23, 18:13, and 22:54. It turns out that in Luke’s estimation, distance is a tensive rather than absolute quality. For instance, in 16:23, distance awakens the formerly sleepy conscience of the rich man, wallowing in a sea of torment, as he contemplates God’s mercy for poor Lazarus.

It can also be a sign of humility, as it was for the tax collector who stood “far off” from the temple (Luke 18:13). Paradoxically, the tax collector was closer to God in the knowledge of his sin than the Pharisee was in the conceit of his good works.

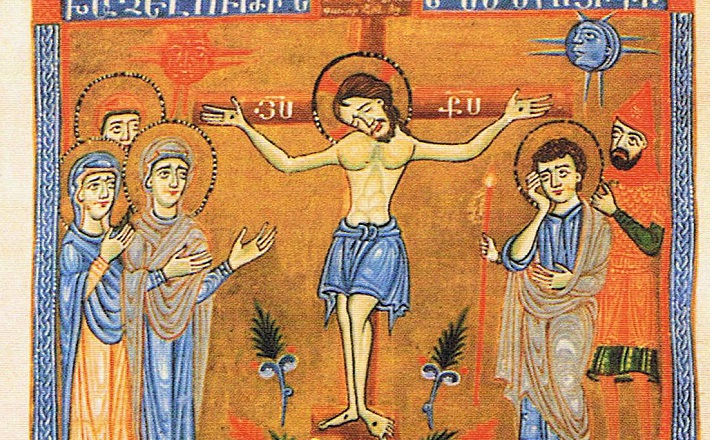

As a witness to the “spectacle” of Jesus’ death, the Roman soldier watches as a matter of duty rather than devotion (Luke 23:47). The realist artist, Joseph Hirsch, gives us “eyes” to see this distance in his work, The Crucifixion (1945). Hirsch places the viewer behind the crucified, with all but Jesus’ left arm obscured by the cross itself.

Instead of Christ, an object of religious devotion, the viewer sees the round face and well-muscled torso of a Roman soldier, apparently whistling a cheerful tune as he aims his hammer at one of the iron nails that will fasten Jesus’ arm to the cross.

“The Crucifixion reflects a grotesque activity treated as an ordinary task,” comments Robert Henkes.6

Hirsch succeeds in conveying the deep disconnect between Christ’s passion and the mindless exercise of duty. However, in Luke’s masterly command of the narrative, even this distance collapses: “When the centurion saw what had taken place, he praised God and said, ‘Certainly this man was innocent’” (47).

To be sure, this text invites its readers to turn the page, to follow Jesus’ acquaintances and the women who joined him from Galilee, to see what will happen next. Readers familiar with Luke will recall the return of the prodigal son, will remember how it was with the father who saw him, how he was filled with compassion “while [his son] was still far off” (Luke 15:20). Though we may be far from God, God is never far from us.

Even so, on this Passion Sunday, perhaps the sermon should linger in the dangerous space of Luke’s gospel, standing at a distance, “watching these things” (49).

Notes:

1 Karl Barth, Deliverance to the Captives (Eugene: Wipf & Stock, 1978), 76.

2 Ibid., 77-81.

3 Ibid., 80.

4 Ibid., 78.

5 Fred B. Craddock, Interpretation: Luke (Louisville: John Knox Press, 1990), 275.

6 Robert Henkes, The Crucifixion in American Art (Jefferson: McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers, 2003), 76.

March 20, 2016