Commentary on Luke 19:28-40

In today’s Gospel text, we find a man who must enjoy living on the edge.

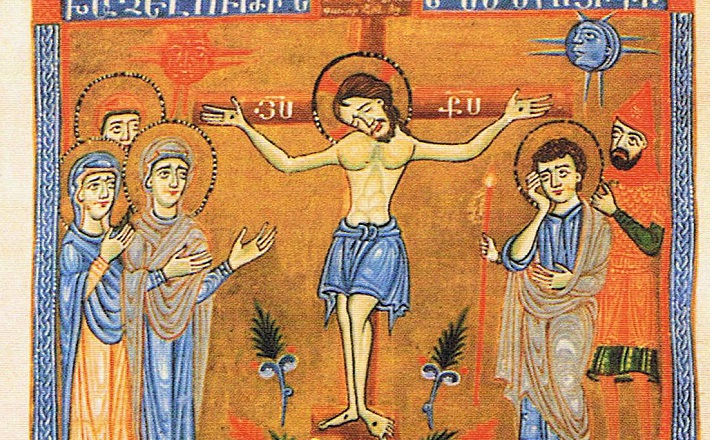

Jesus is a mysterious figure throughout the gospels, but here in Luke we get a distinctive glimpse into the ministry of our Lord. (One of the obvious mysteries that should be highlighted is the absence of palms in this story about Palm Sunday. We only find palms mentioned in John 12:13, 18.) Our attention in examining this week’s reading will involve exploring three questions.

What did Jesus think was going to happen on a Passover trip to Jerusalem? The Passion narrative, as a whole, is the most coherent part of the Jesus story, and so here we find much more agreement than we do in the literary representations of Jesus’ ministry in the other gospels. Nevertheless, Jesus decides to go to Jerusalem during the feast of Passover. Although not the most celebrated feast in the second temple period, Passover is, arguably, the most volatile and political. Passover is meant to invoke and memorialize the divine act of liberation of the Hebrews from Egyptian oppression. The blood of the lambs on the doorposts of the Hebrews saved them from the death that visited Egypt. Further, the Passover feast serves as a kind of shorthand for the entire Exodus experience — leaving Egypt, the parting of the Red Sea, God’s election of Israel at Sinai, the giving of the commandments, the wandering in the wilderness, and the eventual movement into Canaan. God’s triumph over the greatest superpower of its day must have resonated in the minds of the Jews in their second temple celebrations of the event. The political — nay, the revolutionary — runs through the entire feast. This explains why Pontius Pilate and his legions would have left the comfortable confines of his palace in Caesarea Maritima for the parochial space of Jerusalem.

The Romans distrusted associations, crowds, and gatherings such as the one we find in Jerusalem. For example, in his letter to Pliny the Younger, the emperor Trajan (c. 111 CE) wrote, “When people gather together for a common purpose — whatever name we may give them and whatever function we may assign them — they soon become political groups.” Put bluntly, give people enough time and space and they will soon turn against you. This suspicion, already embedded in this scene, haunted the Christian movement on its path to legitimacy under the rule of Constantine.

They had a reason to be concerned. Roman imperialism placed heavy burdens — both human and financial — on its conquered provinces. Portrayed by Augustus and his successors as a positive circumstance, even as a Golden Age for humanity, imperial Rome generated feelings of hatred and contempt from many of its subjects. Pointing to their feelings, the writer Tacitus said, “[The Romans] rob, they slaughter, they plunder — and they call it ‘empire.’ Where they make a waste-land, they call it ‘peace.’” Thus, when Jesus decides to go to Jerusalem, he is placing himself in a dangerous situation — a cauldron of political intrigue and a potential disruption of the pax Romana (i.e., the Roman peace).

What role does Zechariah 9:9 play in our understanding of this text? Many commentators point to this prophecy from Zechariah as the backdrop for the events that take place in this scene. Matthew attempts to follow the prophecy slavishly. Luke picks up the gist of the reference, following the Gospel of Mark. (John makes no mention of an animal carrying Jesus on his final visit to Jerusalem.) Outside of reading it against Zechariah 9, the narrative is more mysterious than candid. Luke’s story is the only one that tells of their placing Jesus on a colt. And while there is much in this procession scene that bespeaks royalty, there is no place in the Hebrew Bible where we find kings riding on colts like this. So while it is clear that the “triumphal” entry into Jerusalem is meant to praise Jesus as God’s envoy or agent, it is not as clear that Jesus is a triumphant king riding into his capital.

The echo of Zechariah 9:9 may have been a creation of the church, specifically the gospel writers, who either read Jesus’ actions that day as a reference back to the prophet or introduced it into the story to clarify Jesus’ status. By contrast, this echo, which runs throughout the Synoptics, may indicate that Jesus fully realized and took on the mantle of his messiahship. Most likely, the invocation of Zechariah 9 represents a combination of fact and interpretation. In other words, Jesus rode into Jerusalem on a colt. Nevertheless, a Hebrew Bible passage helped to shape the narrative as we have it, but it did not create it. Consequently, the prophecy serves to heighten the drama of the Gospel narrative.

The location and those praising Jesus are a little ambiguous, as well. The exact relationship between Bethany and Bethphage is uncertain. Bethany was more familiar to early readers than Bethphage. Some believe that Bethphage was a district of which Bethany was a part. According to John 12:1, it was the home of Lazarus and his sisters. Of interest is Luke’s omission of the supper at Bethany with Simon the Leper. The pilgrimage is simpler. Jesus would have been part of a large caravan of pilgrims. Thus, whether it was everyone in the group, or just “the whole multitude of the disciples,” who praised Jesus appears to be of little consequence.

Why does Luke downplay the political significance of Jesus’ final trip to Jerusalem? The answer may lie in Luke 19:38, “Peace in heaven and glory in the highest.” This is a clear echo of the angels in 2:14. In contrast to the other gospels, Luke presents a Jesus who represents peace. Was this an attempt on his part to disassociate Jesus from the enemies of Israel? Is it a tacit acknowledgement that acting on behalf of freedom is a dangerous thing? I doubt any of us will ever know. All of us are ambiguous characters. In fact, it is precisely at the edges of existence where we encounter God the strongest.

March 20, 2016