Commentary on Jeremiah 23:1-6

Many readers of these comments will have multiple definitions and images of leadership circulating in their imaginations.

They will have experienced leadership in diverse ways. We blame many others for a lack of leadership even as we are uncertain of what constitutes leadership. While the multiplicity of terms for leadership and books about leadership may be a relatively recent phenomenon, the experience of failed leadership is not new.

There is sufficient background information provided in prior posts on this text. See the links to past commentaries on this passage by Fred Gaiser, David Garber, and Elna Solvang. This post will focus on developing a conversation between the text in Jeremiah and contemporary audiences.

Jeremiah 23 does not provide a definitive definition of leadership, despite the promises articulated in the later verses of this reading. It does, however, provide terms to describe failed leadership. The failed leaders are ones who have destroyed the community they were to lead.

Rather than gathering the people for a common enterprise that leads to thriving, they have scattered and driven away those who depended on their leadership. They have not “tended” to the people within their realm of responsibility. Stated in the terms used in the previous three sentences, their failure has been and is matched in many contemporary institutions.

In the context of circa 600 BCE, the leaders have, it appears, sold out to the powerful vested interests — priests and prophets to the interests of royalty and the wealthy, royalty to the perpetuation of its own power and wellbeing. It may be tempting to draw straight lines to equivalent vested interest today, but to do so would be to ignore a dramatic change in context.

Today “interests” are interlinked with individualistic and consumerist demands in the rhetoric and reality of global markets. A “me first” culture complicates any correlation between then and now. Leaders can hide exploitation behind a claim to be giving consumers what they demand. Or, each of us can demand services that ignore their impact on the common good. If I do the latter, I become complicit in the demise of the “flock.” I also am not “tending” to the flock. I too am scattering rather than gathering. The text, then, even is no longer only about a nebulous and nefarious “them” apart from myself.

Even though we cannot draw direct equivalents between then and now, the text of Jeremiah does push beyond generic or paradigmatic leadership failure. The persons hurt by the failed leadership are defined by the first person singular pronoun “my.” Those suffering from failed leadership are “the sheep of my pasture,” “my people,” and “my flock.”

God has a stake in this development. God’s people are hurt and, if God is God, then the hurt caused by failed leadership produces a problem for God. The text of Jeremiah does not assert leadership principles, whether constructive or destructive. The text is not didactically pragmatic; rather it announces the attention of God and the events that ensue from that attention. If contemporary audiences recognize a level of complicity in the failure, then those audiences have to come to grips with God’s attentiveness to those who are scattered by its conduct, whether intended or not.

The failed leadership was not merely lost opportunity. If the flock — God’s flock — is scattered it makes no difference what was intended. The condition of being scattered has to be addressed because it is an outrage; any continuation of the status quo becomes an evil.

In terms of the text of Jeremiah failed leadership was doing evil. God first focuses on the evil doing of the leaders, the “shepherds.” The opening “woe” sets the tone. The “therefore” of verse 2 is a common pivot as prophetic preaching moves from indictment/charge to the announcement of the consequential judgment. Here, however, the opening “woe” anticipates the judgment announced after the “therefore” and the judgment section reiterates or expands on the charge/indictment.

The reiteration or expansion is not superfluous; it shifts to a direct charge. It moves from “the shepherds who … scatter the sheep” to “you who have scattered my flock.” You, that is, the leaders/shepherds have driven away my, that is, God’s people. This active scattering and driving away is at the same time described as a lack of attending to the people entrusted to them.

Lack of attention and active scattering and driving away go hand-in-hand. We might say sins of omission and commission overlap; at the very least the distinction blurs. The text sums it up as “your evil doings.” God will attend to those “evil doings” with the clear implication that God’s attending will be, to put it mildly, an undesirable outcome. It will be the “plucking up,” “pulling down,” “destroying” and “overthrowing” announced in Jeremiah’s call (1:10) and repeatedly spelled out in other sections of the book.

Failed leadership creates a storyline that ends with scattering in exile. That is the end of the story, the existing leadership (or that portion that survives the scattering) cannot create a new chapter. The devastation is too thorough; the creative capacities have been squandered and are now depleted in exilic scattering.

A new agent is needed. It is important not to rush to the hopeful closing verses of this lectionary unit, for the starkness of the reversal will be lost and the hope trivialized. The words are not simply giving the hearers a psychological boast to face their exilic day. The words promise a new reality, a new existence. It is way more than an attitude shift.

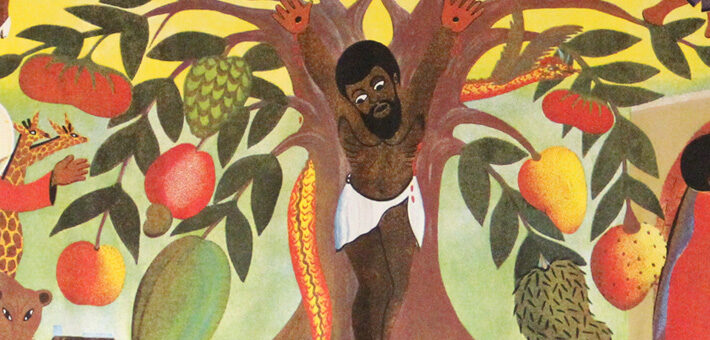

Psychological boasts and attitude adjustments seek to get us back on track. They renew our agency. But the text does not speak of our agency. Overwhelmingly, the change in the latter verses is toward the work of God. God promises to do the opposite of the failed leadership. God will gather, not scatter as past leadership has (be it ancient or our own). God will bring creative thriving for all — the “be fruitful and multiply” echoes with Genesis 1 where it is a blessing extended to far more than human creatures.

This is a promised future far different from that promised in our current economic rhetoric of “creative destruction” and “disruptive innovation.” The latter may have brought prosperity to many, but its failures lead to a communal depletion and scattering no less than that of the exile of Jeremiah’s time.

“Gathering” and “tending” — especially God’s — cannot be made to dovetail with any survival of the fittest social and economic ethic. The hopeful and hope-filled future promised by God is not yet here in its fullness. Our failed leadership, despite its very apparent failures, continues to contest God’s announced future and in the process continues to scatter and do evil.

Holding the two directions of these six verses together in one sermon without homogenizing them will lead to a sermon that ends with petitioning such as in the Lord’s Prayer: “Thy Kingdom Come!” Two things must be preached: judgment for what continues to fail to “tend” and thus “scatters” and the promise of God’s refusal to let the results of “evil doings” be the last word.

November 24, 2013