Commentary on 1 Timothy 6:6-19

The passage 1 Timothy 6:6-19 deals with true riches.

It consists of two main paragraphs: First, the author describes behavior that provides contentment and mentions things that lead to temptation. Second, he gives further ethical advice, which he labels “the good fight of faith” (6:12).

Usually, Bible passages about material wealth cause some amount of discomfort or even reprehension among audiences in our modern North Western hemisphere, which has a strong materialistic orientation. On a global scale, many of us would, after all, qualify as “rich.” Moreover, we often tend to associate personal success and happiness with material affluence. Therefore texts such as 1 Timothy 6:6-10, 17-19 that pose questions regarding riches might be considered a challenge to our entire cultural and economical system.

The preacher of our passage should take note of the fact that, on the one hand, the New Testament features several other texts with a similar attitude toward material wealth as in 1 Timothy 6:6-10, 17-19. Jesus, for example, said: “You cannot serve God and wealth” (Matthew 6:24; see also Luke 16:9, 11, 13).

The Greek term for “wealth” that Jesus used is mammonas; it is transliterated from the Aramaic and denotes earthly goods, yet in a derogatory sense. In the pointed saying of Jesus, the “mammon” appears as a “false god” that gets in the way of true worship of the real God.

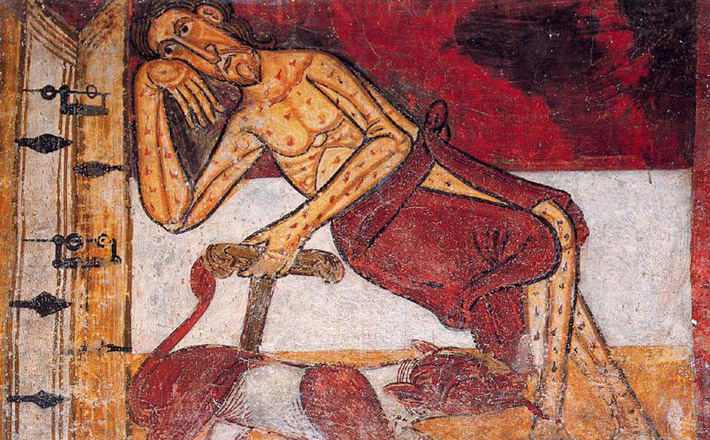

The Church has also recognized that Jesus had a “preferential option for the poor.” Throughout his life, he showed love and compassion and cared for all who were at the bottom of society, namely the poor, sick, outcast, and those whom others considered sinners. Especially the Gospel of Luke and the book of Acts contain various stories that criticize rich people (e.g., Luke 16:19-31; Acts 5:1-11).

On the other hand, it is important to realize that these stories display people who rely on their material prosperity and have little ultimate concern for God. In the parable of the Rich Fool, for instance, Jesus describes the pleasure of a hedonistic person who thinks that his abundant earthly goods will secure his future (Luke 12:16-21; see also the apocryphal Gospel of Thomas 63).

His “insurance,” however, turns out to be void because he will die within a day. The dilemma with such a this-worldly orientation is spelled out in our passage from First Timothy: “…for we brought nothing into the world, so that we can take nothing out of it” (6:7). What is being criticized, then, is rather “the love of money” and “the eagerness to be rich” than material wealth as such (6:10, see also verse 9 and 2 Timothy 3:2). The love of money provides temporary satisfaction, but the love of God lasts forever.

It is also helpful to reflect on the association of material wealth and politics within the context of the Roman Empire during the first century CE. For the most part, riches could only be acquired through continuous cooperation with the Roman administration. Those who were rich, therefore, usually supported a system that oppressed the vast majority of the population for the benefit of only few at the center of the Empire.

Being a counter-cultural movement, early Christians opposed this system and envisioned a more equal distribution of material resources. This is, for instance, conveyed in the story of how believers shared their possessions in Acts 4:32-37 (see also the episode of Ananias and Sapphira in Acts 5:1-11).

On the other hand, wealthy people were appreciated as “benefactors” in early Christianity. Luke mentions that many women who accompanied Jesus and his twelve disciples “provided for them out of their resources” (Luke 8:3). Likewise, the apostle Paul drew on the financial support of benefactors for his travels and missionary activities. He had a secretary at his service to whom he would dictate his letters (see, e.g., the brief greetings in Romans 16:22 by Paul’s scribe Tertius). That person was likely paid by Phoebe; she is introduced in Romans 16:2 as a “patroness” of Paul and many others, suggesting a person of considerable status and prosperity.

It is, therefore, inappropriate to affirm in a wholesale fashion that early Christians criticized material wealth. Instead, of crucial importance is the attitude of the person owning it. Material wealth can get in the way of putting one’s trust in God, and it can be a hindrance to following Jesus (Mark 10:17-22). Yet many of the church ministries and services depend on financial resources of those who are willing to share them. Therefore, those who have riches “are to do good, to be rich in good works, generous, and ready to share, thus storing up for themselves the treasure of a good foundation for the future, so that they may take hold of the life that really is life” (1 Timothy 6:18-19).

Further recommendations for behavior follow in the passage about the “good fight of faith.” The author of the letter suggests that “there is great gain in godliness combined with contentment” (6:6), and recommends “righteousness, godliness, faith, love, endurance, gentleness” that will lead to eternal life (6:11-12). The word “contentment” renders the Greek term autarkeia, which conveyed the important Stoic concept of not being bothered by external circumstances.1

“Godliness” translates the Greek word eusebeia and can also mean “religion,” “piety,” or “devotion.” It was frequently used in the context of Greco-Roman worship. Godliness has already been recommended to Timothy in 4:7-8: “Train yourself in godliness, for, while physical training is of some value, godliness is valuable in every way, holding promise for both the present life and the life to come.

It is worth noting that specifically love, endurance, and gentleness describe behavior that is the opposite of how Paul, before his conversion, acted when pursuing the followers of Jesus Christ. Then he was “a blasphemer, a persecutor, and a man of violence” (1 Timothy 1:13); now he trusts in the power of Christ for his ministry (1 Timothy 1:12). Therefore, Paul himself is a good example of proper behavior for Christians; that is, he is an example of a life that provides true and everlasting riches.

1 Lea, T. D./Griffin, H. P., 1, 2 Timothy, Titus (The New American Commentary, vol. 34, Nashville: Broadman & Holman Publishers, 1992), page 167.

September 29, 2013