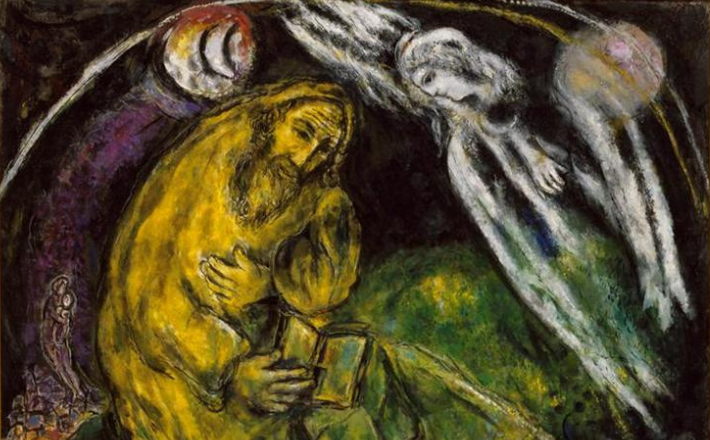

The prophet Jeremiah got pretty tired of having to be the one to tell the truth. In a world where people in power insisted that everything was going to be ok, Jeremiah was the person proclaiming what turned out to be correct: Jerusalem would be besieged and conquered by the Babylonians, the temple would be looted and destroyed, and the elite and powerful of the land would be exiled or killed. The future was most decidedly not going to be ok.

Of course, proclaiming in graphic detail the coming destruction of an entire community and everything it holds dear is not a great way to “win friends and influence people,” as the saying goes. Jeremiah had little to show for his trouble but rejection and persecution. And yet, despite his own suffering, the prophet just would not quit.

In the narrative (Jer 20:1-6) that immediately precedes the thematic Old Testament passage appointed for this week (Jer 20:7-13), Jeremiah has just spent a very uncomfortable night imprisoned in stocks. He has been put there by the priest Pashhur, an important temple official, who objected to God’s word of judgment brought by Jeremiah upon the valley of Hinnom (also known as “Tophet” and, later, “Gehenna”) just outside of Jerusalem. Ever defiant, as soon as Jeremiah is released, he turns to Pashhur with a more personal curse: Pashhur’s new name will be “Terror-All-Around,” because he will witness the fall and plundering of Jerusalem. Then Pashhur and all his household “shall go into captivity, and to Babylon you shall go; there you shall die, and there you shall be buried, you and all your friends, to whom you have prophesied falsely” (Jer 20:6).

The contrast been false and true prophets (and priests) is a recurring theme in Jeremiah: the ones who “say ‘Peace, peace,’ when there is no peace” (Jer 6:14), versus Jeremiah himself, a lone voice of dissent. Jeremiah feels not just a duty, but a compulsion, to tell all of the terrible truth. Even when he tries to reject God and be silent, his body resists: “If I say, ‘I will not mention him, or speak any more in his name,’ then within me there is something like a burning fire shut up in my bones; I am weary with holding it in, and I cannot” (Jer 20:9). To me this is an extraordinary stanza of poetry—vivid, evocative, and deeply moving.

This is perhaps the moment in this essay when I am supposed to advise you, Working Preacher, to be more like Jeremiah: to be consumed by your vocation, to be on fire for the Lord, to be unafraid to speak truth to power.

But let’s face it: Jeremiah was not a healthy person. He lived a life of suffering and fear. Most of the time someone really was out to get him—either to thwart his ministry or to kill him outright.

The world needs some Jeremiahs, to be sure. But the world also needs more leaders—priests and prophets, kings and presidents, preachers and teachers, friends and influencers—who tell the truth. With more of those kinds of leaders, there is less of a need for the prophets who give over their well-being, or even their very lives, for the sake of proclamation.

Sometimes telling the truth does involve confronting a coming disaster, whether it is a global threat like climate change or nuclear war, or a more personal catastrophe, like those that come in the wake of addiction, cruelty, or apathy. Many other times, though, telling the truth involves affirming the radical promises of God: that all are beloved, that there is no shame that cannot be overcome, that there is no hurt that cannot be healed, that death does not have the last word.

Even Jeremiah’s truth-telling about the imminent Babylonian invasion was not all bad news, because he rooted his hope in God’s promises. There were prophecies of judgment, yes, but also of God’s deliverance and fidelity. Ending this week’s Old Testament passage, sandwiched between the prophet’s lament over his persecution and another lament ruing the day he was born, is a stanza of doxology: “Sing to the LORD; praise the LORD! For he has delivered the life of the needy from the hands of evildoers” (Jer 20:13). As with any lament psalm, Jeremiah’s concluding doxology is a reminder to himself, to his listeners, and, later, to his readers that God is worthy of praise and capable of providing deliverance. God has been faithful in the past and promises faithfulness in the future.

A preacher has (at least!) two different kinds of opportunities to respond to the word of the Lord as it comes to us from the prophet Jeremiah—and neither of them involves spending time in the bottom of a muddy cistern (Jer 38:1-13). The first, as I have already emphasized, is to be a leader who is a truth-teller. Do not pretend problems are smaller than they are. Faith is not a smoke-and-mirrors act, where we cross our fingers that no one will notice how bad things are. Faith is imaginative, life-giving hope in the face of this world’s grimmest realities.

The second opportunity preachers have is another variation on the theme of leadership: preachers must empower their listeners to be truth-telling leaders themselves. After all, on any given Sunday, the preacher is not the only leader in the sanctuary. The people in the pews all exercise influence over somebody—some in profoundly significant ways—whether they are business people, politicians, parents, attorneys, accountants, teachers, truck drivers, or anything else. God does not need us all to be tortured Jeremiahs, but God needs us all, each and every one, to be truth-telling leaders grounded in the promises of God.

-Cameron