“Sir, we wish to see Jesus.” Do we really? Do we actually want to see Jesus? Or do we pretend, feign interest, when in fact, seeing Jesus just might cause a kind of discomfort we’d rather not experience.

I am rather amazed by these Greeks. I get that in John they represent the world. The world that God loves. The world that God saves. The world that rejects a presence of God that just might cause a rather cataclysmic theological event.

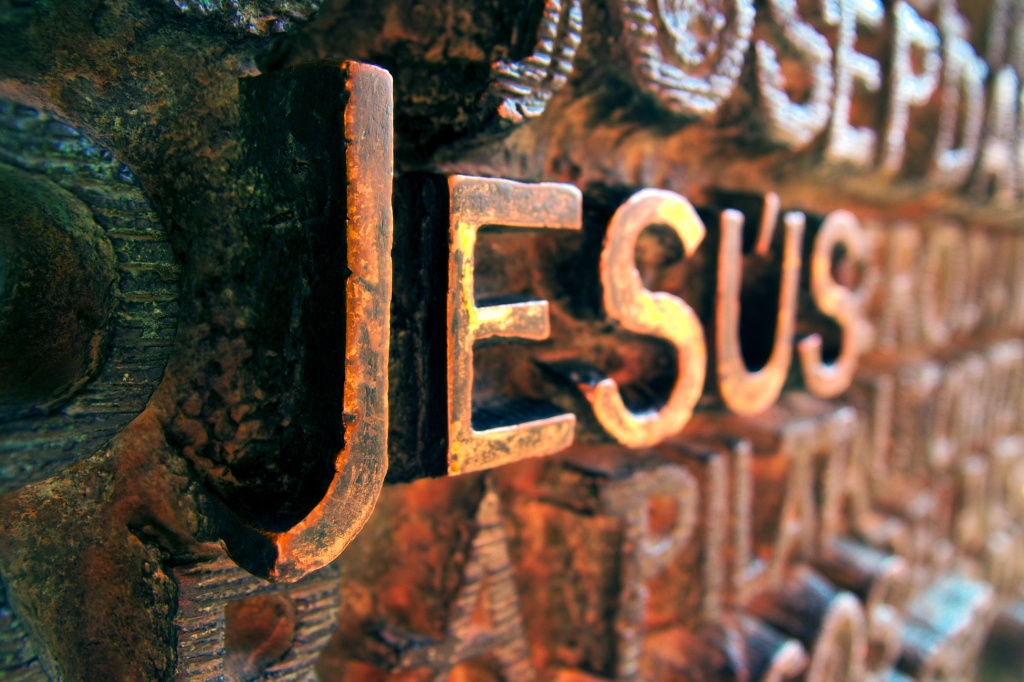

But at the same time, they represent us. And they ask what we should ask. As it turns out, this verse is carved into pulpits around the world. Why? Because we preachers need this reminder. Our sermons should never be simply information about Jesus. They should enable the seeing of Jesus. The experiencing of Jesus. If our sermons only provide a point, only summarize the Gospel, only hand out perfunctory condensations of what Jesus means, well then, as my former colleague, Gracia Grindal used to say, we could just as well send an email. Then everybody could stay home, put on another pot of coffee, and read the Sunday paper.

The request of the Greeks is critical for our time. They ask to see. They don’t request proof. They don’t ask for an argument. They don’t need an apologetic. They just want to see. They get what “come and see” is all about — and invitation to be. An invitation to abide. An invitation to relationship.

And yet, how often do we ask to see, even demand sight, but yet have already decided what is worth seeing — and what isn’t. Much of what is happening now, in leadership, in our churches, in the way we interact with each other, especially on social media where we can conveniently set aside responsibility and accountability, we see only so as to judge, to maintain our own self-righteousness, not to get to know, to learn, or to understand the other. As one wise person I know said, leadership does not mean leading an attack.

I think that much of what is wrong with religion, with Christianity, with church and its varied denominations, with, in my context, seminaries, is the conviction that we need to justify, prove, or validate the presence of God, the need for God, the certainty of God, all with an accompanying appropriate piety, rather than embodying, giving witness to, the fact that a theological perspective might actually matter for making sense of the world. We spend an extraordinary amount of time and energy constructing a probable justification for our God who cannot be justified by our standards.

We advocate for curricula, in our seminaries and in our churches, which assume knowledge about God is equivalent to an experience of God. We talk about God as if God were not in the room. We talk about God as if God were simply the subject of our supposed dialogue rather than the essential presence in our conversations. And we talk about God as if “I AM” was merely a recollection of God’s revelation rather than a new way God might be revealing God’s very self.

How much we have descended into idolatry. How much we rely on our own manifestations of God rather than waiting for disclosure from God. How much we trust our own divine constructs rather than hold out for a chance that God might startle us once again. Theology has turned into certainty. And so we have followed suit (or, perhaps it’s the other way around), operating only with the principles of assumption and correction and labeling, perpetuating the binaries of right and wrong, good and bad, moral and immoral, thereby creating distances so vast it’s hard to imagine strategies that might mend the chasms of our own construction.

And so, instead of wishing to see Jesus at work, Jesus in our midst, we seek to control Jesus rather than remaining open to the Spirit. We assert parameters for God’s activity rather than expecting surprise. We insist that we can determine divinity or regulate God’s revelation. And when we come up short, rather than realizing our misguided assumptions about God, we try harder to execute our plans.

When it doesn’t go our way, when we find ourselves faced with our own fixed expectancies of God, we quickly back-peddle, hoping to avoid the discomfort of recognizing our own need for forgiveness.

The request of the Greeks is an open-ended wish. They want to see, as it seems, absent of predetermined outcomes or preconceived notions, at least according to the text. And the result is that Jesus speaks the truth that is his very self. The truth we never want to see. The truth we wish we could un-see. The truth about God and that is God and the truth about ourselves. The hour has come.

Karoline