Commentary on John 4:5-42

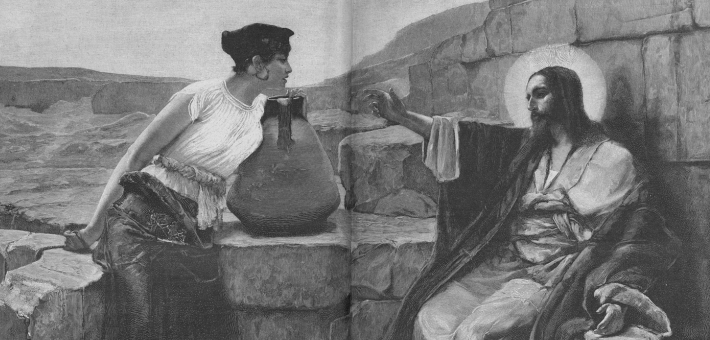

The story of Jesus and the Samaritan woman begins as a literal journey. Jesus leaves Judea, a province in the south, and is traveling to Galilee, in the north. By choosing to travel to Samaria, and not just through it, he encounters not just a Samaritan woman and her story, but the story of the place where she draws water. As we encounter this account in John’s Gospel, we can see how John’s telling of this story shapes our understanding of it.

What’s her story?

Most accounts of the Samaritan woman’s story create a biography out of two details: She came to the well at noon (4:6), and she was not married to the person she lived with, though she had been married five times before (4:18). From these details, it is often assumed that she was ostracized from her community, because noon is a hot time of day to draw water and she is seemingly by herself, and because her marital history is understood to imply poor moral choices.

Neither implication holds much water based on the context. First, given how those in the city who hear the woman’s proclamation of Jesus immediately come to see him, she seems to be a trustworthy figure in the community (4:30), with “many Samaritans” believing in Jesus “because of the woman’s testimony” (4:39). Second, while some wealthy women in Rome may have had the legal authority to divorce their husbands, this was only possible with the permission of their fathers (or familial equivalents) and would not have been likely or possible for a poorer woman in the province of Samaria. Therefore, she most likely had five husbands due to tragedies, either death or being divorced or both.

Regardless, this woman’s story is so much more than those hypothesized implications. She engages Jesus in conversation, not just once but twice, around questions of theology. While she does not understand Jesus’s double entendre (“living water”; see below), she has great company in John’s Gospel. Everyone misunderstands Jesus, especially initially (2:19–22; 3:1–11; 4:31–34; 6:32–35, 51–52; 7:33–36; 8:21–22; 11:12). What she shows, beyond misunderstanding, is a desire for what Jesus offers (4:15), even if it makes her question her own faith and practice (4:19–20). When Jesus tells her something about her life that she has not told him (4:18), she uses the opportunity to quiz a prophet (4:19) about practices of worship and theology. Ultimately, she is a theologian and an evangelist, leading others to Jesus. That is her story.

What’s the story of Jacob’s well?

The place that Jesus lingers, “tired out by his journey,” is repeatedly called “Jacob’s well” (4:5–6, 12). While there are many accounts of Jacob in Genesis, there is no story of a well belonging to him. Nevertheless, there are several stories about wells; they were the watering places of Israel’s first families in more ways than one. Abraham’s servant meets his master’s future daughter-in-law at a well (Genesis 24:10–61); Abraham’s grandson, the eponymous Jacob, meets his wife Rachel at a well, at noon (Genesis 29:1–20). Even Moses meets his wife at a well (Exodus 2:15–22).

In all these stories, a man travels to a foreign land, meets a woman at a well, and they discuss water. Once water has been drawn, the woman leaves the well to tell her community about the man. Her community offers hospitality to the man, and the encounter concludes with their marriage. A well in a story was the equivalent to a modern romantic comedy’s meet-cute, where the two main leads encounter one another for the first time. Such scenes set up expectations for what is to come.

This backstory makes sense of Jesus’s conversation with the woman about her marital status (4:16–18), as that is what people who knew this tradition would expect to happen when two people met at a well. It is also likely why the disciples objected to Jesus speaking to a woman (4:27), something that happens elsewhere in the Gospel without comment (11:1–44; 20:11–20). Of course, this narrative sets up the expectations of a marriage at this well, only to flout them; Jesus is the bridegroom (3:29), but not for a wedding here and now.

Lastly, it matters for this “story” that Jacob’s well was, in fact, a well. That seems obvious, but it is essential for understanding how the Samaritan woman misunderstands Jesus’s offer. Jesus says that if she had known who was asking her for a drink, she would have requested “living water” from him (4:10). The underlying double entendre here is that the Greek word for “living” water also means “running” water—in other words, water from a river or stream, rather than well-water. Since a well can be poisoned or tainted, running water was understood to be safer and more valuable. But even with this misunderstanding, she still wants what this running (living) water does: It will forever quench her thirst, and that is what she desires (4:14–15).

What’s John’s story?

Lastly, we encounter the Samaritan woman in the context of John’s Gospel, meaning that we, as John’s audience, meet her soon after Jesus has spoken one-on-one with another person—Nicodemus (John 3:1–10). Nicodemus and the Samaritan woman are opposites in many ways: They embody gender, class and status, and ethnic and religious differences. The setup for each encounter also differs: Nicodemus initiates the conversation with Jesus, while Jesus initiates the conversation with the Samaritan woman, and the former is at night (3:2) while the latter is at noon (4:6).

After the conversation is initiated, however, the similarities stack up. Jesus responds to each of them by introducing a new topic that includes a word play (born again/from above; living/running water). Both misinterpret Jesus, and Jesus repeats his teaching and expounds on it. At that point, Nicodemus is confused and stops speaking (until we meet him again later in John’s Gospel: see 7:50–52; 19:39–42), while the Samaritan woman requests what Jesus offers despite continuing to interpret his offer differently.

In this way, Nicodemus and the Samaritan woman indicate how others will receive Jesus in the Gospel. Whether Jew or Samaritan, some will be curious but cautious, while others will be curious and will invite others into their curiosity. The commonality, though, is Jesus’s hospitality, revealing himself to those who seek him.

March 8, 2026