Commentary on Genesis 32:22-31

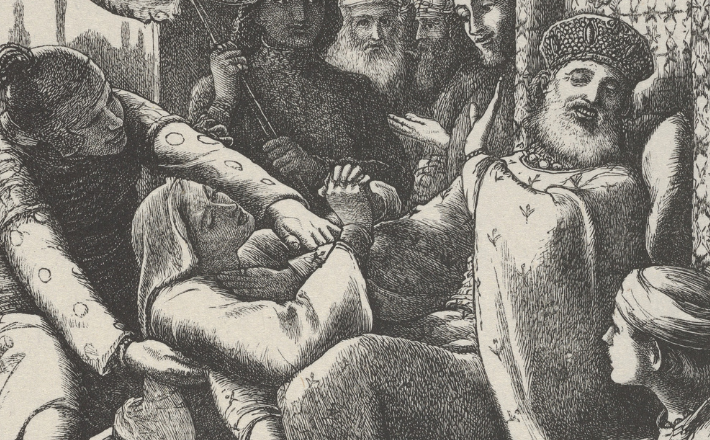

Wrestling is the most honest, most profound metaphor for the life of faith. Wrestling is how we are invited to encounter scripture. And it is how we are invited to encounter God.

The storyline build

Genesis 32 is one of the most enigmatic scenes in all of scripture.1 The reader’s eyes see as dimly in the night as do Jacob’s. Even as the sun rises and Jacob limps away, the questions linger. Who was Jacob’s opponent? What did this nocturnal wrestling match accomplish? What is significant about Jacob’s renaming as Israel? And who emerges victorious?

As our text begins, we find Jacob bound for home after 20 years in Paddan-aram, where he had fled after exploiting Esau’s overzealous hunger, convincing him to trade the cherished right of the firstborn for a bowl of lentil soup (Genesis 25:29–34). Additionally, aided by his mother Rebekah, Jacob had deceived his aged, blind father Isaac out of the blessing intended for Esau (27:1–40).

During Jacob’s two-decade sojourn in Haran, he has become exceedingly rich and the father of 12 sons who will become the namesakes for the 12 tribes of Israel. God has proven to be with Jacob at every turn, working continually for his good and ensuring Jacob’s success in every endeavor.2 Now, only one final tension remains for Jacob to confront: his besmirched twin brother Esau, whom we last saw in the narrative plotting to kill Jacob out of revenge (27:41–45).

When Jacob learns Esau has come to meet him, accompanied by 400 men, Jacob is understandably afraid. He strategically separates his family into two camps so one can escape should Esau attack, sends gifts ahead to attempt to appease his brother (32:3–8, 13–21), and prays (32:9–12). As a result, “Jacob was left alone, and a man wrestled with him until daybreak” (32:24).

In this corner, from parts unknown

The narrative is initially ambiguous about the identity of Jacob’s assailant, first identified simply as “a man” (ish, verses 24, 25). The reader, thus, has been conditioned to wonder whether this is Esau getting his revenge by blindsiding Jacob in the night. But we quickly realize this is more than a mere man, for the struggle endures throughout the night, a simple “touch” (naga) dislocates Jacob’s hip, and there is a fascination with the blessing this figure can give.

Some have proposed this is Jacob’s own internal wrestling with his troubled past, but as Gunkel observed over a century ago, “one’s hip does not become disjointed in a prayer struggle.”3 This is a real, bodily encounter.

Jacob comes to recognize his opponent as God in human form. After successfully wrestling a blessing from his opponent, Jacob renames the place Peniel, meaning “face of God.” His opponent had earlier hinted at this divine identity when offering an explanation for Jacob’s new name “Israel” (verse 28), and in the following chapter Jacob says that seeing Esau’s face is like seeing “the face of God” (33:10). In the received form of the text, the intention appears to regard Jacob’s opponent as God (see also Hosea 12:3).

What is your name?

The name “Jacob” literally means “heel,” a reference to his heel-grabbing from the womb in a quest to be born first (25:26). This, along with Jacob’s subsequent trickery and deceptions, has led many to view Jacob negatively. (Interestingly, in professional wrestling parlance still today, the “heel” is the “bad guy.”) The larger phenomenon of the trickster, both biblically and in folklore, however, provides a different perspective.4 Jacob the trickster is never condemned or punished by God. In fact, God ratifies the “stolen” promise just one chapter later (28:13–15), and even when Jacob is the recipient of trickery himself, it ends up advancing the promise (29:15–30:24).

In the midst of the wrestling, Jacob receives a new name: “Israel.” There is a delightful Hebrew wordplay: at Jabbok (yabok) a “man” wrestled (yabeq) Jacob (y’qob). Wenham cleverly paraphrases verse 25 as “he Jacobed him!”5 This subtly connects Jacob’s original name with the activity of wrestling. While there is also some debate on the etymology of “Israel,” the narrative offers its own interpretation: “You have striven with God and with humans and have prevailed.” “Israel” means “to wrestle with God” (or perhaps “God wrestles”).

This is not a redemptive moment for Jacob where the new name symbolizes a change in character or a new way of being in the world; it is not a coming-of-age, reaching greater maturity, or a giving-up of his deceptive ways to make him deserving of the promise that he had already received and that had been ratified by God 20 years prior.6 He will again deceive Esau by promising to meet him in Seir but instead settling in Succoth (33:14–17), and he will cross his hands when blessing his sons at the end of his life (48:13–14). The new name Israel joins the original name Jacob in the narrative that follows. He remains ever the trickster (Jacob) and is commended as one who has wrestled (Israel) throughout his life—even as early as the womb (25:22–23)—with humans and with God, and prevailed. Perhaps the biggest surprise in the story is that even by God’s own assessment, Jacob … wins!

Don’t let go!

Jacob has proven to be a more than formidable opponent, even for God! Jacob holds his own all night! And notice, it is God who must ask to be let go before daybreak, even after injuring Jacob with a cheap shot (32:25–26). Jacob/Israel’s refusal to let go of God is what raw, honest faith looks like. Faith is not just passively submitting to God; it is grappling, contending, tenacious, and persistent. It is wrestling: grabbing hold of God and refusing to let go, despite the struggle, the time, the risks, the injury. Because the blessing is worth it. “I will not let you go, unless you bless me” (32:26b).

This is the story of Jacob. Of God’s people Israel, who will grow from his 12 sons. And it is our story too. The preacher knows this well; every sermon is a wrestling match. We grab hold of a text in pursuit of a blessing for our people. Sometimes the blessing comes easily; other times it comes at great struggle and cost. The preacher may wish to ask the congregation what their “Peniel” moment is: When have they wrestled with God, seen God’s face, and what are the battle scars that have been imprinted on their life and faith?

Because sometimes faith feels like wrestling. Yes, we can choose to let go, but at what cost? Or we can hold on. Like Hulk Hogan dropping the big leg or John Cena’s five-knuckle shuffle, we can learn some new moves and holds to strengthen us for those wrestling matches to come. Because there is more than a title belt on the line. There is a blessing!7

The blessing on offer to us from Genesis 32 is that even in the midst of real struggle in the darkest of nights, if we refuse to let go, yes, we may come away injured, marked, limping—as did Jacob. But if we just hold on, we might also come away with a blessing … and having caught a glimpse of the very face of God.

Notes

- For my full appraisal of this scene, see John E. Anderson, Jacob and the Divine Trickster: A Theology of Deception and YHWH’s Fidelity to the Ancestral Promise in the Jacob Cycle, Siphrut 5 (Eisenbrauns, 2011), 130–71.

- I argue that God is intimately connected to, and at times directly implicated in, Jacob’s many deceptions, all with the intent of moving toward fulfillment of the promise of land, descendants, and blessing originally given to Abraham in Genesis 12:1–3.

- Hermann Gunkel, Genesis, trans. Mark E. Biddle, Mercer Library of Biblical Studies (Mercer University Press, 1997), 349.

- Anderson, Jacob and the Divine Trickster, 22–40, 44–47.

- Gordon J. Wenham, Genesis 16–50, WBC 2 (Word, 1994), 295.

- Anderson, Jacob and the Divine Trickster, 130–132, 160–169.

- Can you tell I am an avid professional wrestling fan yet?

October 19, 2025