Commentary on Genesis 32:22-31

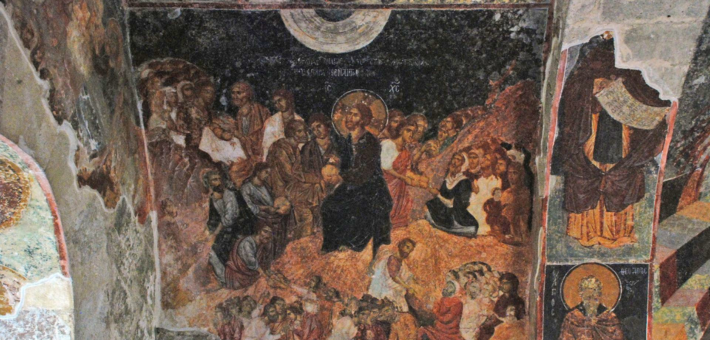

This story appears foreboding, with Jacob alone at night. It is also playful, with the stream’s name punning on his name (verses 22-24) and anticipating the further pun on the verb, “to wrestle” (*’bq, in verses 24-25). The scene unfolds mysteriously, with Jacob wrestling a nameless “man” whom he will recognize as an ’ělōhîm (verse 29).

The plural noun ’ělōhîm applies to “gods” in general (Judges 9:9, 13), and for minor divinities subordinate to Yahweh (for example, Psalm 86:8; see also Job 1:6, 2:1). It also denotes “other gods,” in other words, gods other than Yahweh, as in the Ten Commandments in Exodus 20:3 and Deuteronomy 5:7). It also refers to God (for example, Genesis 1:7, 16, 25) as a sort of plural of majesty. The noun ’ělōhîm can even denote also the ghost of a dead person (1 Samuel 28:13, referring to the dead Samuel; see also Isaiah 8:19). The word has a wide range of usage. All this raises a question in the story: what sort of ’ělōhîm is wrestling with Jacob?

Hosea 12:4-5 takes the ’ělōhîm in this scene as an “angel.” This is not surprising, since in ancient Israel angels were low-level divinities (see Zechariah 12:8). Their identity and power derive from the major deities whom they serve literally as “messenger” (the Hebrew word for “angel,” is related to the verb “to send”). An angel can be both divine in nature and human in form, as with the figure in Genesis 32. So no wonder Hosea 12:4-5 represents the figure this way, but does Hosea 12:4-5 settle the matter for Genesis 32?

There is no evidence that an angel was assumed in Genesis 32 itself. Since biblical authors usually show little or no difficulty saying what they want audiences to know, Genesis 32 may deliberately present a mysterious figure. The story ends with Jacob naming the site Peniel (“face of God,” verse 30; see the variant Penuel in verse 31), following his declaration of “seeing God face to face” (verse 30). Since this motif was at home in the ritual experience of the Jerusalem Temple (Psalms 11:7, 17:15, 27:4, 42:2, 63:2, and 84:7), the “god” that Jacob believes he has experienced may be the god of the sanctuary site who has appeared to him in human form.¹ Who was that?

Before the name of Yahweh was revealed to Moses in Exodus 6:3, the patriarchs knew this god as “God Almighty,” in Biblical Hebrew El Shadday (Genesis 17:1, 28:3, 35:11, 43:14, 48:3, and Exod 6:2; see also Genesis 49:25). This El could have been the god of the sanctuary and/or a god of Jacob’s family (see also Genesis 49:25, “by the God of your father, who will help you, by the Almighty, who will bless you”). The story hints in this direction with Jacob’s, new name Israel (verse 28), which includes El, the divine name generally associated with the patriarchs and matriarchs in Genesis (for example, not only El Shadday, but also “El-Elohe-Israel,” New Revised Standard Version, or “El god of Israel” in Genesis 33:22; see also “El the eternal one,” in Genesis 21:33, “the Everlasting God” in New Revised Standard Version).² In time, this divine figure came to be identified with Yahweh, as narrated in Exodus 6:2-3 and as reflected in the combination of the name of Yahweh with El-titles (for example, Genesis 21:33). English translations such as the New Revised Standard Version often render the word for El in these contexts as “god,” a grammatical possibility that facilitates the Bible’s conflation of Yahweh and El as a single god. So El may be the older figure lying in the background of the narrative.

In the end, however, Jacob’s encounter is not simply a divine puzzle that he wants to know (“Please tell me your name” in verse 29). The story also highlights the mystery of Jacob’s engagement with the divine. Who is God for Jacob-Israel? What does God intend for Jacob?

It is Jacob’s destiny to be returning to the land (verse 22) and to be Israel (verse 28). It is to struggle with God and with humans (verses 24-25, 28). When the ’ělōhîm says to Jacob, “you have striven with God and with humans and have prevailed” (verse 28), the italicized words in this speech reverse and play on Jacob’s new name. Israel’s destiny is even to be wounded by God (see verses 25, 31), and still somehow to prevail (verse 28), as it has so often in history. It is also Israel’s destiny to be blessed by God (verse 29) and to see the face of God (verse 30); and it is no less to keep God’s teaching, signaled by the story’s reminder of Israel’s duty to observe dietary law “to this day” (verse 32). Overall, the story is about Jacob’s mysterious identity—and destiny—to be Israel in relationship to a mysterious God. This story, set in Israel’s distant past, envisions its ongoing destiny “to this day.”

Notes:

- Here we might compare the goddess Anat in conflict with the human Aqhat at a shrine, in Ugaritic Narrative Poetry, ed. Simon B. Parker, Society of Biblical Literature Writings from the Ancient World 9 (Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature, 1997), 59-62. See “her temple” in line 39 of column V as the setting for the scene that follows in column VI when they clash.

- See the classic treatment of these El titles in Frank M. Cross, Canaanite Myth and Hebrew Epic: Essays in the History of the Religion of Israel (Cambridge, MA/London: Harvard University, 1973), 46-60.

August 6, 2023