Commentary on Luke 17:11-19

“Did none of them return to give glory to God except this foreigner?”

If Jesus’ words never strike me as strange, if Jesus’ words never cause me some sense of unrest, if Jesus’ words never trouble me, then I can be sure of one thing: I can be sure that I am missing something important.

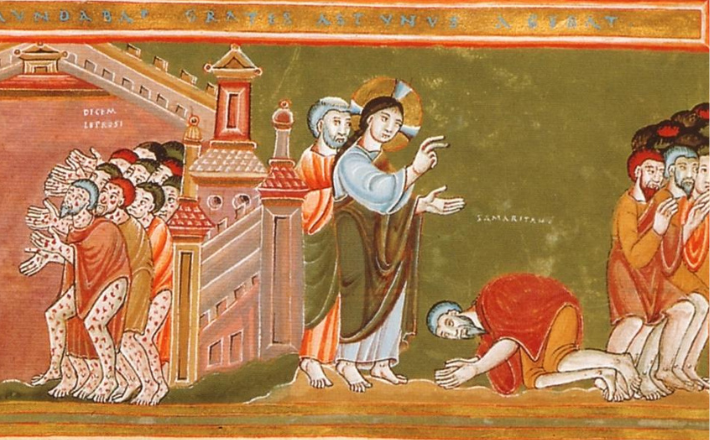

Luke here narrates one of Jesus’ miracles of abundance. Instead of the healing of an individual, Jesus here makes 10 people suffering from a skin disease well. The New Revised Standard Version Updated Edition correctly opts for “skin disease” rather than “leprosy” as it has become clear to scholars that the modern form of skin disease we call “leprosy” is not identical to the condition Luke and other Gospel writers refer to as lepros.

As Matthew Theissen has argued, leprosy did not exist in the ancient Mediterranean context in which Jesus healed and Luke wrote.1 Instead, he argues, the sloughing off of the skin that resembles a decomposing corpse pointed to the origins of impurity: death. Here, Jesus resists this deadly force, the very source of the impurity, not just healing a disease but battling the encroachment of death upon human life. In short, this is a healing that points to Jesus’ extraordinary power to defeat death and its minions even before he faces a Roman cross and a tomb.

Jesus’ abundant healing, however, remains unreciprocated by the bulk of its recipients. Only one of those healed returns to give him thanks. The one who returns is a Samaritan, a foreigner (in Greek, an allogẽnēs). Earlier, in Luke 10, Jesus highlights a Samaritan for the mercy he shows a stranger left for dead by bandits, a clearly surprising conclusion to a story we now know all too well. That it would be a familiar enemy who might deliver us from danger is an alarming confrontation of our most cherished values.

Just one chapter earlier, right after Jesus begins his sojourn to Jerusalem (9:51), a Samaritan village chooses not to welcome him. Incensed disciples, having just been granted by Jesus “power and authority over all demons and to cure diseases” (9:1–2), feel emboldened to strike back. They offer to destroy the village and its inhabitants, only to be confronted by Jesus’ rebuke. In short, the wider Lukan context prepares us to see in the Samaritan who returns a surprising end to this miraculous healing.

And yet, it seems that Jesus’ statement is more than a mere observation of fact, a neutral note. Jesus’ words also seem to have an edge of condemnation and dismissal. As I once heard Anna Carter Florence note in a sermon, Jesus does not even speak to this healed leper but over him. “This foreigner” is barely present in this scene, though of the 10 who were healed, only he has acted faithfully. Why does Jesus seem to dismiss this act of thanksgiving? Why does he seem surprised that an outsider would comprehend the enormity of his healing but nine insiders would misunderstand?

It may be that recognizing the experience of the foreigner is essential in proclaiming this text. After all, the experience of the foreigner is unenviable. Familiarity is fleeting for the foreigner. On the one hand, the foreigner’s new home is never quite home. Many will dream of returning to the land of their birth, but this first home is a place that no longer really exists. Once the foreigner has left home, the home itself changes, but so also does the one who migrates to a new land. For most, returning home is a dream; it is pure nostalgia that can easily rot into resentment, decline into despair. Their new home is their true home, though it may never feel that way.

The Hebrew Scriptures are all too familiar with the experiences of the foreigner. Among this week’s lectionary texts, Jeremiah 29:1, 4–7 exhorts the prophet’s fellow Israelites to embrace lives as foreigners in Babylon. He tells them to seek the welfare of the city and contribute to its thriving. Build homes, for the homes to which you hope to return are no longer. Create new family links, for your kin are with you and are not to be found back in the land you once called home. Seek the welfare of the city of your exile, for it is now your city. And yet, at the very same time, Jeremiah invokes God’s promises to God’s people, declaring that their return to Israel was assured by God.

These are the incredible tensions of living as a foreigner in another’s land. We might also recall Leviticus 13:34 exhorting its readers and hearers to recall their former state as enslaved people in a foreign land as they consider the treatment of others. The experience of living as a foreigner is a hermeneutical and ethical key of sorts for these passages and these experiences. To experience or even remember exile and displacement is to draw near to a tangible experience of God’s mercy and judgment. Though they are no longer foreigners, the memory of being foreigners is no less acute.

These reminders of the tangible realities accompanying the life of the foreigner strike me as particularly pressing these days. In our politics and wider culture, we tend to hear “foreigner” deployed as an epithet all too often. And yet, we can only decry the presence and powerful stories of foreigners in our midst by neglecting our own exilic ancestry, both personal and biblical.

Moreover, decrying the presence of foreigners in our midst leads us to miss a critical theological insight. The foreigner can approach the grace of God in a particularly insightful way, a path of insight that may now be lost to many of us. After all, the foreigner understands the sting of oppression. She understands the usually unavailing nostalgia that accompanies exile. She understands the rootlessness that characterizes the foreigner’s life. These are all experiences that shaped the story of Israel and its Messiah. Without them, the narrative of God’s action in this world is incomplete.

The foreigner is a vital presence among us. The foreigner is a reminder of the pain of displacement many of us have felt. The foreigner is a reminder that God’s promises know no boundaries or borders, that God’s grace will not abide by the arbitrary lines we draw between ourselves and others, that God consistently finds the most unlikely proclaimers of the good news as the best choice of all to announce God’s will.

Notes

- Matthew Thiessen, Jesus and the Forces of Death: The Gospels’ Portrayal of Ritual Impurity within First-Century Judaism (Baker Academic, 2020), 43–68.

October 12, 2025