Commentary on Luke 17:11-19

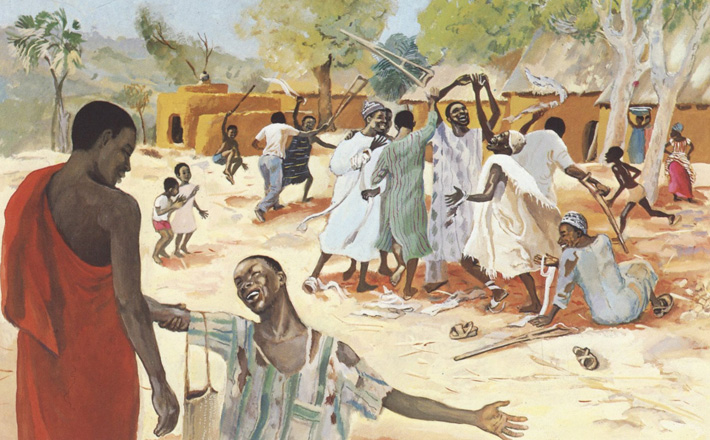

The story of the grateful Samaritan offers us another image of who and what matters to Jesus and should, therefore, matter to us.

The story draws attention to two important themes in Luke:

1. Jesus’ care for the marginalized (here ten lepers and at least one of them doubly marginalized, a Samaritan)

2. The appropriate response to Jesus, a response of faithful recognition and gratitude. It is not unusual for the two to occur together in Luke; the marginalized seem well placed to see him for who he is as he has seen them for who they are.

In the introduction, we are reminded that Jesus has set his face to go to Jerusalem (9:51), where he will arrive in chapter 19. He is in the region between Samaria and Galilee; Jesus frequents boundary spaces and is about to cross a social boundary again by his association with lepers and with a Samaritan.

As he enters a village, ten lepers approach calling out to him but keeping their distance because they are unclean. They address him as master, a term used in every other instance in Luke by the disciples. Jesus immediately sends them to show themselves to the priests to confirm their healing, and en route they are in fact made clean, following the pattern of the earlier cleansing of a leper at 5:12-14.

Cleansing of lepers is an identifying marker for Jesus’ mission in 7:22: “Go and tell John . . . the lepers are cleansed.” This episode also evokes the story of Naaman the Syrian, the OT lectionary text for today, which Jesus mentions in his inaugural sermon at 4:27. His attention to outsiders and marginalized people is evident from the start, and he highlights it in that speech, in response to which his hometown audience tries to throw him off a cliff. Here, as in the story of Naaman the Syrian, the recipient of healing and grace is a foreigner (although in an interesting twist we find that, in the case of Naaman, the prophet Elisha is from Samaria).

In the text for today, after the healing of the ten lepers, the focus narrows to one of the ten, who alone turns back glorifying God and prostrating himself at Jesus’ feet thanking him. This verb for thank is the one used when Jesus thanks God for the bread and cup at the last supper (22:17, 19; see also Paul in Acts 27:35). It is the basis for our word Eucharist.

Only after he prostrates himself in thanksgiving do we learn that the one who has turned back in this borderland is a Samaritan.

Samaritans were the unlovely outsiders of Jesus’ day, and we can think about who that might be for our congregations and ourselves. These unappealingly different and unwelcome outsiders, along with outsiders generally, are received positively by Jesus in Luke. We see this most notably in the parable of 10:25-37, in which it is a Samaritan, and not the respectable religious people, who demonstrates love for his neighbor by showing mercy to a wounded stranger.

Samaria (the place as opposed to Samaritans as a name for the people), mentioned in verse 11, is mentioned only here in Luke but is mentioned positively in Acts 1:8, where the mission of the church includes Samaria, and in 9:31, where it is included in a summary statement of growth and peace. Elsewhere in the NT it is only mentioned in John 4, again positively.

The heart of the story unfolds in three steps:

1. the healing

2. the turning back and praising God (literally glorifying God)

3. the prostration and thanksgiving at Jesus’ feet.

Then each of the steps are interpreted by Jesus in ways that highlight his care for the marginalized and the rightness of the response of the Samaritan to this care:

1. “Were there not ten made clean?” Jesus asks. “But the other nine, where are they?”

2. “Was none of them found to return and give praise [literally give glory] to God except this foreigner?”

3. And finally Jesus’ response to the Samaritan prostrate with thanksgiving at his feet: “. . . your faith has made you well [literally saved you].” Jesus addresses the same phrase to the woman at the anointing (7:50), the hemorrhaging woman (8:48), and the blind beggar (18:42).

Jesus’ life is framed by people glorifying God, with the shepherds at his birth (2:20) and the centurion at his death (23:47). And here as elsewhere it marks Jesus’ work of healing and restoration (5:25-6; 7:16; 13:13; 18:43). To respond rightly to Jesus is to praise and glorify God.

The Samaritan’s thanksgiving and prostration at Jesus’ feet; his recognition that God is at work when Jesus notices and heals hurts and brokenness that are not noticed by others; his understanding that to thank Jesus is to glorify God: this is the manifestation of faith that makes well, as the NRSV puts it here. And this seems to come easiest to the people who have received most from Jesus, the ones who are otherwise ignored, scorned, untouched. As Jesus observes in the case of the anointing woman (7:47), the one who has been given much also loves greatly. Love that springs from gratitude is the essence of faith.

We do not know whether the other nine were Samaritans, but in identifying the Samaritan only after he alone is prostrate at Jesus’ feet, the narrator suggests that it is perhaps his having been noticed and cleansed in spite of his double-marginalization, his double experience of life at the edge, that creates his deeper gratitude.

There is no doubt something to be understood here about the people who live on the margins of our communities, who are treated as invisible or unlovely because of how they look or who they are or where they come from. Jesus clearly notices and loves them and calls us to do the same.

But we might also consider the parts of us that are hidden in the borderlands of ourselves where we may least want to be seen and most need to be touched. Jesus, who is not afraid of borderlands, does not mind meeting us in those places, and it may be that by recognizing him there, we will find in our deepest selves a new outpouring of the grateful love that makes well.

October 13, 2013