Commentary on 2 Kings 5:1-3, 7-15c

“How can we pray for you?”

For the seasoned, even not-so-seasoned pastor, this question often brings a request for physical healing. By nature of leading a community of faith, the pastor often comes to the forefront of the darkest times of sickness and death. We understand that we are called to pray, and we believe in an omnipotent God with power over all diseases. It is hoped that this week’s biblical narrative helps us to better reflect on prayer, sickness, and the presence of God.

The opening verse of the passage describes a deeply paradoxical figure in Naaman. He is an Aramaean, thus a political enemy of Israel, yet it is clear that he has won a degree of favor with the Lord. He is a powerful general, yet he suffers from leprosy (or another skin condition, the Hebrew is uncertain). Although he holds a prestigious military office with direct access to the king, he carries this physical affliction with enormous social stigma.

This leprosy is so overwhelming that it overshadows the rest his personhood. He is so desperate that he listens to a rumor from his mistress’ servant of a healing prophet in Israel. Naaman appeals to the king for permission to go to Israel to seek out this prophet for healing.

A few words on the social context of this passage may clarify the seemingly strange narrative. Ancient Israel was a socially embedded society. Goods and services were exchanged not out of money (coinage would not be invented for a few more centuries). Instead, goods and services were exchanged out of social relationships.

A farmer would share crop with the extended family simply because they were extended family. The fisheries would share the catch within the clan and close friends, not out of profit, but out of obligation to maintain the relationships. Value, honor, and loyalty regulated and maintained society more than profit and legal jurisprudence.

Therefore, it is completely sensible that Naaman traveled down to Israel with an enormous cargo of gifts to present to the king of Israel. The gifts were not for trade, but the foreigner Naaman was trying to create a social bond with the Israelite king. By creating a social bond through gifts, it obligated the Israelite king to give hospitality, and in this case to find a cure for the general’s leprosy.

But these gifts put the Israelite King in a bind. He could not refuse the gift, as it would be like a new bride and groom refusing a wedding gift from a guest (“Sorry Uncle Charlie, but we won’t be needing that salad spinner.”) By accepting the gift yet not curing the leprosy, the king would violate the required social responsibility. He could sense an impending confrontation with the Aramaeans. Thus, he cries, “Am I God, to give death or life, that this man sends word to me to cure a man of his leprosy? Just look and see how he is trying to pick a quarrel with me” (verse 7).

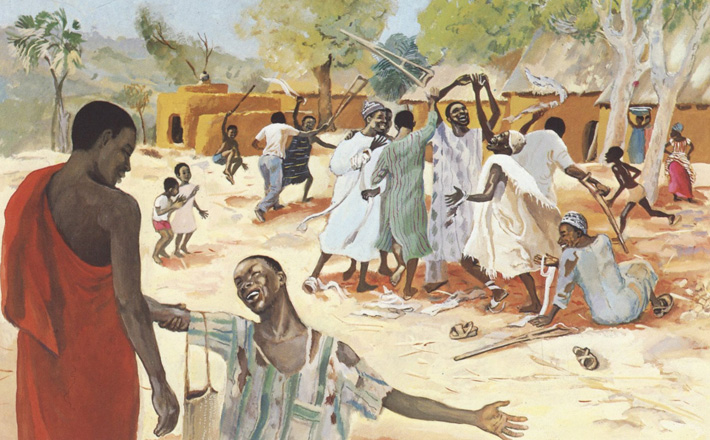

Thankfully, Elisha intervenes and tells the king to send the Aramaean general to the prophet. Verse nine paints a picture of irony: a military division of horses and chariots parked in front of a prophet’s house. Elisha would not even meet the general in person, but merely dismisses a servant to give the instruction, “Go, wash in the Jordan seven times, and your flesh shall be restored and you shall be clean” (verse 10).

But Naaman has traveled many miles to Israel with his affliction. He assembled the vast payment and was diverted from the royal palace to the house of the prophet. And now, it is not the prophet, but the servant of the prophet who gives a one sentence instruction — an instruction seemingly too simple, too mundane to have any efficacy. Naaman is angry, but the anger is more likely a mask for deep disappointment and sadness. He intends to just return back without even trying.

But the servants gently persuade the general. This is the third time in the passage when the lower and weaker character gives wisdom to the lofty (verse 3, 8). The servants gently, yet cogently, persuade Naaman to just give it a try. He does, and just as Elisha’s servant promised, “His flesh was restored like the flesh of a young boy, and he was clean” (verse 14).

The healing begets a profound question. Why heal the Aramaean general? The land of Israel had many more lepers, who continued to live with their affliction. Did they not deserve healing as well? Did the healing serve to show the unquestionable sovereignty of God?

Luke 4:27 helps us to reflect on this incident, “There were also many lepers in Israel in the time of the prophet Elisha, and none of them was cleansed except Naaman the Syrian.” Not only does God reserve the right to using his sovereign healing, this instance was also a judgment on Israel.

People mistakenly equate sickness with a lack of faith. But in this example, the healing was not a result of faith but more despite its lack! Naaman is sick, frustrated, and embarrassed. With the help of his servants, he finally exhibits “just enough” faith to get healed. But sometimes, that is all it takes.

October 13, 2013