Commentary on Exodus 17:1-7

Exodus 17:1-7 is a narrative that shares much in common with the complaint narratives that have preceded it.

Its structure is the same as the other stories: (1) the people encounter a potentially devastating threat to their well-being; (2) they then complain to their leadership; (3) their human leaders bring the complaint before God; and (4) God saves them by various means, in this case, by providing water. Even the content of their complaint is unremarkable. They ask for water to drink and then deliver a version of the now familiar refrain: “Why did you bring us out of Egypt, to kill us and our children and our livestock with thirst?” (v. 3) While they do not explicitly compare their circumstances in Egypt to their situation in the wilderness as they do elsewhere (16:3; cf. 14:11), the mere mention of Egypt in this context suggests that the people continue to regard their present state as much worse than their state as slaves in Egypt. With all of these similarities between these complaint narratives, it bears considering why it is that Moses later names the site of this narrative Massah, “Test,” and Meribah, “Quarrel” (v. 7).

The key seems to be that the word “complaint” has been replaced by the word “quarrel” (ryb). The Hebrew root often refers to legal disputes, but in non-legal contexts, it is translated as “strive” or “struggle,” which suggests open antagonism between Moses and the people. One cannot help but consider the hopeful words of 14:31: “Israel saw the great work that the Lord did against the Egyptians. So the people feared the Lord and believed in the Lord and in his servant Moses.” In spite of divine help, the difficulty of the journey has eroded the people’s trust. Hostility has now replaced belief, and Moses is afraid for his life. He asks, “What shall I do with this people? They are almost ready to stone me” (v. 4). He is not in an enviable position out in the wilderness, stuck between the Almighty and a people quickly losing patience with privation and with their leaders who seem to keep taking them from one desperate situation to the next.

God’s response to this crisis is as forbearing and nurturing as it has been in the other complaint narratives in spite of the fact that the story is remembered as one in which the people questioned God’s presence with them: “the Israelites quarreled and tested the Lord, saying, ‘Is the Lord among us or not?’” (v. 7). The narrator does not characterize God as being in any way frustrated or angry at the people’s quarreling and testing. Indeed, God’s directions to Moses demonstrate an astute awareness of the nature of this specific crisis and provide an appropriate response to it. There are two components to the divine instruction:

- Moses is to take some of the elders with him and go ahead of the people. The miraculous act he will perform there is going to be in their sight (v. 6b), presumably so that they can go back to the people and serve as witnesses, which will certainly bolster the people’s confidence in the leadership of God and of Moses.

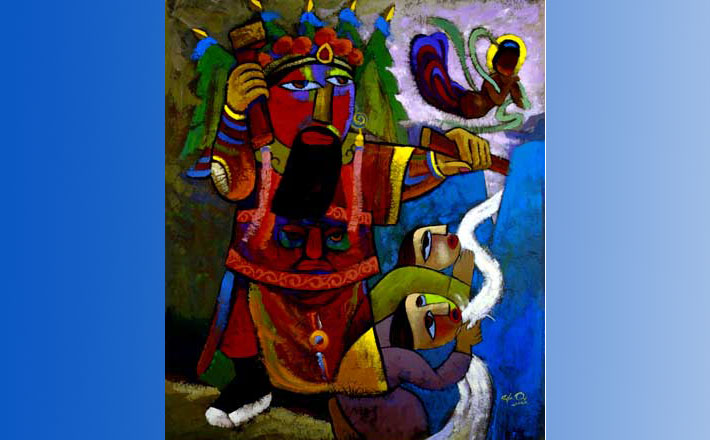

- Moses is to take the staff with which he struck the Nile — and, thus, rendered it undrinkable (7:20)–and strike a rock from which water will then flow. God’s own self will be physically manifested in some way on this rock (v. 6). Once again, the importance of the elders witnessing this divine act is key. Key, also, is the fact that Moses is using the staff which served as tool in the people’s redemption from slavery, the slavery about which the people seem to have developed a form of amnesia. The significance of the staff is clear: God used Moses, and the staff in that first plague to rescue the people; God, Moses, and the staff are no less powerful out in the wilderness. There is no need to despair and turn on Moses. God is still present, powerful, and working through Moses. (Although see the twin of this story in Numbers 20:2-13.)

The difficulty of life in the wilderness is clearly taking its toll on the people, and Moses is finding himself the focus of their ire, although the people are questioning God’s role in their present plight as well (see vs. 2c, 7c). The divine response to this crisis meets the obvious physical need for water, but it also serves to address the deep uncertainty the people are expressing that God is not with them and that Moses is an unreliable leader who does not have their best interests at heart. Although Moses’ father-in-law, Jethro, has not yet met with him and advised him to share the load of leadership (18:17-23), it is clear that Moses and the people need a group of leaders drawn from the people who can act to reassure the community of Israel and to provide support for Moses as they make their way through the wilderness on the way to Mt. Sinai.

The people’s quarreling and testing is born of a stressful environment, and we would do well as preachers to be as compassionate in our treatment of the people’s plight as God is depicted as being. Indeed, a sermon might do well to focus on the wisdom of God’s response to the test the people set with their question, “Is the Lord among us or not?” At some point both communities and individuals will ask such a question, and those people who attest — as the elders of the people did — to the power and presence of God in our midst are tremendous sources of strength. It can be the case that professional clergy are associated with this role, but this story makes clear that the position of witness should not be limited to one individual. It is the task of all who have experienced God’s loving kindness to speak about it and, thus, offer to others reasons that we might trust in God in any circumstances.

September 28, 2014