Commentary on James 2:1-10 [11-13] 14-17

The exposition in last week’s passage, James 1:17-27, can strike readers as abstruse and random; this morning’s lesson, however, is clear and pointed as broken glass.

James poses a hypothetical situation to his readers — or perhaps describes a situation he knows already to be going on. This focal example takes up the themes that James has already flagged up as pivotal for his theology, and shows how a scene from everyday life illustrates exactly the failings against which he had warned readers.

In the first chapter, James has drawn out a vision of faithfulness to God in which we demonstrate our fidelity by reflecting God’s character in our human lives. Whereas life apart from God succumbs to desire, leading people to sin and thence to death, James urges his readers to adopt their identity as true children of God by living in the Father’s way. They need to keep their faithfulness to God whole-hearted and consistent, lest they waver and turn away; and their steadfast faithfulness should be manifest in their action on behalf of widows and orphans, the needy for whom God has shown particular care.

“That’s all very well in theory,” says James, “but let’s look at what actually happens in your congregations.” (James says sunagogê, “synagogue,” but he is probably not making a point about a “Jewish” rather than “Christian” gathering; the two terms are effectively synonymous.) When an elegantly-dressed man — “gold-fingered and in radiant clothing” — visits your church, is he treated as more special than the homeless beggar in filthy rags? James suspects that you give the snazzy dresser a more prominent place, and the fragrant vagrant a more inconspicuous place (“Stand over there, or sit on this kneeler”).

It does not take an advanced degree in theology to tell that such behavior doesn’t go well with what James has put forward as God’s way. In James 1:27, he has reminded readers that “religion that is pure and undefiled before God, the Father, is … to care for orphans and widows in their distress”; by the same token, he says, “God [has] chosen the poor in the world to be rich in faith and to be heirs of the kingdom” (2:5). Whatever we might say about cultivating benefactors whose (hypothetical) gifts might provide sustenance for ministries and programs, James recognizes the temptation to favor people like us, or whom we wish we were, over against people whose affliction reminds us of how contingent our good fortune may be. This is just the half-hearted discipleship that submits to desire: the desire to be comfortable, the desire to be upwardly mobile, the desire to experience only life’s ups, and to be insulated from life’s downs. Such desire fuels litigious efforts to secure our well-being at the expense of others, regardless of their own contingent circumstances. By contrast, whole-hearted faithfulness to God will always require of us whole-hearted faithfulness to the least of Jesus’ brothers and sisters: to orphans and widows, to our naked, hungry neighbors, to wounded and broken left-behind bystanders.

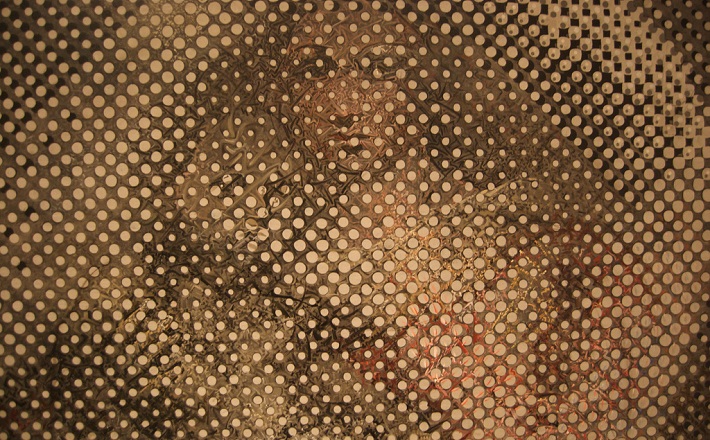

No one wants that kind of life, unless they have been overwhelmed by a different sort of desire. No one wants to look into the true mirror and see a scarred face which hardship has scribed with the seams and wrinkles graven by years of endurance. Yet James insists that this face of one who has known sorrows, who is acquainted with grief, is our birthright. He twice invokes the images of kingship in these verses: the royal law obliges us to love our neighbor as ourself, and the destitute have been chosen to inherit God’s kingdom. James sees in the faces of beggars the resplendent visages of celestial queens and kings; he recognizes that true beauty comes not from the use of costly creams to moisturize our skin, but from our similarity to God’s hungry, chilled children.

(The lectionary permits omitting James 2:11-13. Verse 11 does — confusingly — seem to take it for granted that the congregation tolerates murder; and suggests that if you commit murder, that might lead even to adultery. It’s easy to see why they might skip that! But the assurance in v 12 that “mercy triumphs over judgment” provides a vital balance for the ominous warnings James addresses to wavering readers. Though v 11 might lead to some difficult questions after the service, I would firmly encourage including these verses for the opportunity to pair James’s stringent exhortation to costly discipleship with the reassurance that the God who will judge our half-heartedness will all the more demonstrate mercy to us.)

The very common impulse to show generous hospitality to those who need it least, and to withhold that generosity to those who need it most, exemplifies James’s central emphasis on integrity. There is no integrity, no integration to a faith that cozies up to privilege and turns its back on need. Faith that is not joined-up with consistent action, it is no faith at all. While James is often characterized as anti-Pauline, his emphasis on active faith coheres perfectly with Paul’s own insistence that those who have received the Holy Spirit in being baptized into Christ’s death in order to share his resurrection should jolly well manifest the Spirit’s guidance in the conduct by which their lives reflect the Spirit working through them.

The last paragraph of today’s reading thus sums up James’s point that faith involves more than affirming theological formulas, but a thorough reorientation of one’s life. Faith makes a difference in us. More importantly (in these verses), faith makes a difference in our relations with our sisters and brothers: just as God has chosen needy, broken, bereft brothers and sisters as the visible embodiment of Jesus’ good news among us, so faith reorders our own desires away from securing our well-being by our own efforts, from enhancing our image by associating with glittering celebrities, and summons us to make our friends among the shabby poor, and to trust the provision of God who gives freely to all.

September 6, 2015