Commentary on Lamentations 3:22-33

Lamentations is rarely read or sung in any American churches, but when it is, it’s the passage in today’s lectionary reading. Beautiful hymns such as “Great Is Thy Faithfulness” have helped the church for hundreds of years to find hope and solace in the beautiful cadences of Lamentations 3. Yet when we focus only on these verses of hope in the midst of a book entitled “Lamentations,” we risk missing their point—and indeed, the point of the entire book in which they are found.

The book of Lamentations was written by and for people who had survived an unimaginable trauma with personal, political, social, and theological dimensions. What if everything you relied upon for your security, comfort, identity, sense of God’s presence, and hope in the future simply vanished overnight? For the residents of Jerusalem in 587 BCE, who watched the Babylonians smash the walls of Jerusalem, burn down the temple, knock down the houses in the city, and execute the Davidic royal family, the world seemed to lose all sense of order and coherence. Life suddenly felt chaotic, brutal, meaningless, and hopeless. These emotions and the questions that arose from the traumatic destruction of Jerusalem are reflected in the book of Lamentations.

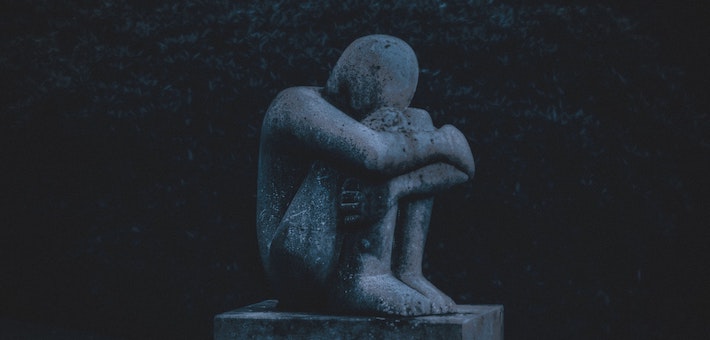

As Kathleen O’Connor interprets the text, the book of Lamentations as a whole offers a theology of witnessing to suffering.1 In contemporary American culture, at least, the expression of pain and suffering is often seen as embarrassing, weak, and even tacky. If something is wrong, then many of us want to know how to fix it and then forget about it. Asking someone else to hear about our pain in detail is considered selfish and cringe-worthy. We should grin and bear the pain instead—especially in Christian communities, where the triumph of Christ’s resurrection often serves as a trump card to force people to rejoice, or the call of Christ to carry our crosses serves to halt any conversation about the pain of our suffering. But Lamentations asks us to sit with grief, either ours or someone else’s, and give ourselves time to feel its texture, weight, and shape.

This can be seen clearly in Lamentations 1, where Daughter Zion—a personified Jerusalem ravaged by the Babylonian destruction—and the narrator repeatedly ask God and the passers-by to “look” at Daughter Zion’s pain (Lamentation 1:9, 11, 12), suggesting that God and neighbor have not paid attention to the tragedy. The only people who do notice are the mockers who heap shame onto Daughter Zion, compounding her suffering (Lamentations 1:5, 7, 8, 21). The narrator and Daughter Zion repeat another refrain throughout the chapter: she has “no one to comfort her” (Lamentations 1:2, 7, 17, 21). YHWH has not consoled her, and neither have any neighbors. If either had paid attention, maybe they would offer both comfort and support.

So, why does the poet go to such lengths to describe in intricate detail the suffering of Daughter Zion (Lamentations 1:1-2, 12, 16, 20)? Perhaps because the poet is asking us to be the one who will pay attention to the suffering, that someone might finally notice. In Lamentations 2:13, the poet struggles to imagine how anyone could adequately bear witness to the immensity of Daughter Zion’s pain; but this struggle to enunciate the truth of another’s suffering is the point of the book of Lamentations, and it is entrusted to us, its readers, as our sacred task.2

Lamentations 3 introduces another character: the geber, or “strongman,” who is expected to defend the city from its attackers (verse 1). He has not only failed in his duty—his own suffering has left him without peace, happiness, energy, or hope (verses 17-18). The geber places the blame squarely on YHWH, who has mercilessly mauled Jerusalem like a bear hunting its prey (verses 10-11). After the text in today’s lectionary, the geber subtly accuses YHWH of failing to hear and save the people who so desperately need divine help (verses 42-65; note verse 42: “you have not forgiven”).

In the midst of those accusations, we find the famous text that tells us: “But this I call to mind, and therefore I have hope: YHWH’s fierce covenant loyalty (ḥesed) never ceases” (verses 21-22; most scholars and translations choose to read with Syriac and Targum here instead of the Masoretic Text). The geber remembers the cornerstone of his faith: unflagging hope in YHWH’s continually renewing loyalty, grace, and mercy (verses 23-24). This declaration of faith sounds very similar to an often-repeated refrain that likely served as a backbone of ancient Israelite faith in YHWH (see also Exodus 34:6-7; Numbers 14:18; Nehemiah 9:17; Psalm 103:8; Joel 2:13; Jonah 4:2; etc).

In the past, this knowledge gave the geber quiet confidence that YHWH would eventually save him from any and all troubles (verses 25-26). The geber even claims that suffering and adversity can be constructive and upbuilding especially for the young, as it builds spiritual grit (verses 27-30). According to these teachings, God will eventually bring salvation, and those who had hope will be rewarded—and presumably will increase their faith. God does none of this out of anger or rage, says the geber; it’s all for our benefit (verses 32-33).

It is important to note that this is not the last word in the book of Lamentations. Some scholars have argued that the seemingly central position of these words within the book centers their theological claim and minimizes the descriptions of suffering that predominate in the rest of the book. Yet Lamentations 4 and 5 break with the tight acrostic patterns of Lamentations 1-2, and thus the book is unbalanced overall—and what seems like a central position given to Lamentations 3:22-33 is a mirage.

Thematically, Lamentations 4 and 5 return to remembering the trauma in excruciating detail, which suggests that Lamentations 3 did not solve the problem or remove the need to voice grief or re-tell the traumatic narrative. Most strikingly, the book of Lamentations closes with a startling series of questions: “Why have you forgotten completely? Why have you forsaken us these many days?” (Lamentations 5:20) The poet asks God for restoration, but ends with a sobering thought: perhaps God has utterly rejected the people, and there is no more hope (Lamentations 5:21-22). The book thus begins with a question (“How?”; Lamentations 1:1) and ends with an implied question (Will you ever take us back?; Lamentations 5:22).

Thus the robust and heroic faith of Lamentations 3:22-33 is part of a larger conversation about traumatized individuals and communities struggling through their own sorrow and grasping for any remnant of a relationship with God. It is a part of faith, but not the final word, and should be carefully used to open avenues of conversation, dialogue, and honest sharing rather than shut them down. Perhaps, within the overall structure of the book, the poet puts these words in the mouth of the geber to remind YHWH of the people’s formerly vigorous confidence in YHWH: “Be the God you long ago promised to be!”

In the lectionary, this text is paired with the famous “Markan sandwich” of two miracles: Jairus’ daughter and the woman with the flow of blood (Mark 5:21-43). Both of these miracles showcase the extreme faith of unexpected individuals who have faced tremendous adversity. Perhaps the voice of Lamentations’ geber can help us think about the suffering felt by both of these recipients of God’s miraculous healing power without reducing them to one-dimensional object lessons that lead us to ignore our pain—and that of others.

Notes

- Kathleen O’Connor, Lamentations and the Tears of the World (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis, 2002), 3.

- O’Connor, Lamentations, 39-43.

June 27, 2021