Commentary on Hebrews 10:16-25

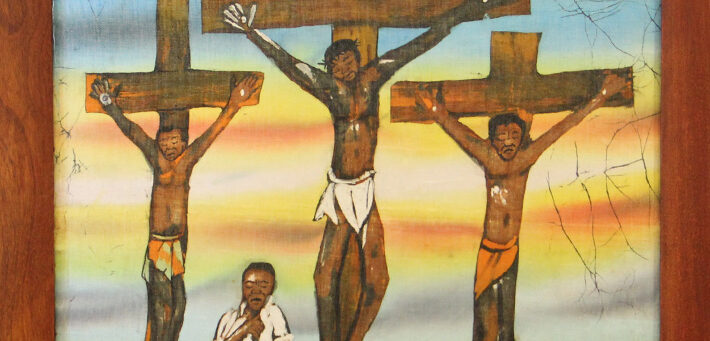

For modern-day Christians, the cross has become purely a religious symbol.

It adorns the walls of our homes and our places of worship, its presence marks our altars as holy places, and we wear it as jewelry. In short, it rarely touches the ground! With its exalted status as the focal point of our faith, the cross has lost its power to scandalize. We bracket the religious meaning from any memory we might carry that in Jesus’ time the cross was an instrument of execution used by the Romans, and reserved for slaves or those charged with treason against the Empire.

Early Christians could not avoid that connection. Crosses were all too common sights at the edges of the cities and along the Roman highways. For these ancestors in the faith, the challenge was to find ways to articulate the religious meaning of the cross in imagery and language powerful enough to transform the immediate horror it represented. Today’s reading from Hebrews is one expression of that quest.

The opening parameter of the reading is a bit puzzling. Verses 16 and 17 seem to bring to a close the previous section, echoing 8:8-12 as they recall Jeremiah 31:31-34 and the “new covenant” that God will write on the people’s hearts. That task that initially belonged to God is attributed to the Holy Spirit, affirming God’s continuing presence and activity on behalf of God’s people. What is remembered is also still an apt expression of how God acts among us in this time after Christ’s crucifixion and resurrection.

Now, though, the writer’s emphasis is on the meaning of the crucifixion for us, and its implications in our lives. The paragraph that encompasses verses 19-25 is the first part of a three-part exhortation that follows on the identification of Christ’s high priestly ministry. This first part is an admonition, and it is followed by a warning (10:26-31) and a paragraph of encouragement (10:32-39).

The admonition that appears in English as a paragraph consisting of several sentences, in Greek is a long, complex sentence of closely linked participial clauses. It consists of two parts–the two-fold Christological basis (verses 19-21) and the three-fold admonition proper (verses 22-25)–introduced by the conjunction “therefore,” emphasizing its dependence on what has preceded it. The author’s theological depth and rhetorical skill is evident in that tight structure as well as in the substance of these verses.

The author begins by establishing common ground with those being addressed by calling them αδελφoι, literally “brothers.” The masculine plural form, however, would be used to encompass an audience including both genders, and that is certainly the case here. The NRSV’s use of “friends” to convey that inclusiveness is certainly appropriate, as long as it is understood to convey familial intimacy and interdependence.

The first of the Christological bases draws on the imagery of the Holy of Holies in the Jerusalem temple. Only the High Priest could enter this dwelling place of God to intercede on behalf of the people, who would wait anxiously outside until the priest had completed his task. Our posture now is different, says the author of our text. We now can approach with “boldness” or “confidence,” on the strength of Jesus’ life offered in sacrifice for us. Unlike the temple curtain, which kept the people separated from God’s presence, Jesus’ death–the offering of his very life–opened a “living way” to God (verse 20).

The second of the Christological bases for the admonition also draws on temple imagery, but in a way that does not fit smoothly with the first. In the theology of Hebrews, Jesus is at once the perfect sacrifice that opens the path to God, and also a “great priest” who can be our human advocate before God (verse 22). Clearly the intent is not literal description, but rather a parabolic approach that draws us in and invites us to contemplate the ineffable truth that is the way of Christ.

The consequences of these Christological truths are expressed in three exhortations. They are conveyed grammatically by the hortatory mood (“let us”), and they elaborate, in turn, on the faith, hope, and love that are the mark of the Christian (see also 1 Corinthians 13).

- The first exhortation concerns our approach to worship, in which we are called to embody confidence and integrity, marked liturgically by “washing” (literally cleansing oneself) and “sprinkling,” an apparent reference to baptism (verse 22) as an initial step into the Christian community.

- The second (verse 23) urges tenacity in maintaining hope, which by definition pulls us forward beyond what we presently see or experience. That tenacity is possible, not through our own strength, but through the faithfulness of the One who stands behind the promises that ground us.

- Finally, we are exhorted to “provoke one another to love and good deeds” (verse 24), in an echo of Paul’s determination that faith not be an abstraction, but come to ethical expression and have consequences for the life of the community as we wait for the Day of Christ’s return.

Like the epistle appointed for Passion Sunday in the Revised Common Lectionary (Philippians 2:5-11), this one too draws us beyond this day and the events that mark it in the gospel narratives, into our own lives as Christians. They push us to reflect on the meaning of the crucifixion for our own lives, and to continue the quest for adequate human language to express the ways of God.

April 2, 2010