Commentary on Psalm 22

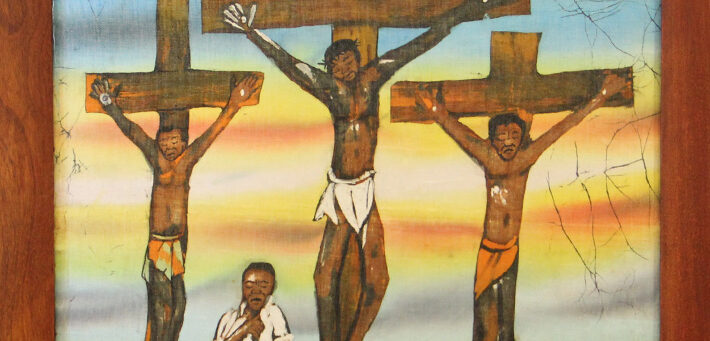

This is one of the Bible’s saddest texts, appropriately read by Christians on Good Friday, the saddest day of the church year. I find myself emotionally drawn into the agony of the speaker, and I also experience the speaker’s joy as he celebrates his rescue and prospect for the future.

But Psalm 22 raises a thorny question for me: Who is the speaker — a Davidic king under attack, Jesus on the cross, or both? As a preacher, I have to choose my stance on that question before I do anything else.

If I opt for the Davidic king, I face a further challenge — how to relate the text to the events of Good Friday. But if I opt for Jesus, then I have to decide how Psalm 22, written centuries before him, relates to Jesus.

Some possible interpretive stances include:

- Psalm 22 as prophetic. It predicts what will happen (and does happen) to Jesus, and he fulfills it.

- Psalm 22 as typological. It reports a pattern of God’s historical dealings that recurs at the crucifixion.

- Psalm 22 as allegorical. Beneath its historical, surface meaning lies its true spiritual meaning (i.e., the besieged king is really Jesus on Golgotha).

I opt for a typological reading. My sermon would somehow review the four obvious literary parallels that Psalm 22 and the crucifixion narratives share. This table summarizes them:

Table of Parallel Motifs

| Motif | Psalm 22 | Crucifixion Narratives |

|---|---|---|

| Main character: a king | Implied in verses 12, 16, 22 | Matthew 27:11, 29, 37; Mark 15:2, 9, 12, 18, 26, 32; Luke 23:3, 37, 38; John 19:3, 19, 21 |

| Cry: “My God, my God …” | verse 1 | Matthew 27:46; Mark 15:34 |

| Public mocking and ridicule | verses 7-8 | Matthew 27:28-31, 39-44; Mark 15:29-32; Luke 23:35-40 |

| Gambling for his clothes | verse 18 | Mark 15:24; Luke 23:34; John 19:23-24 |

In addition to these literary motifs, we also observe that both human figures are servants of God on uniquely intimate terms with their Master. Both figures play a unique role in God’s work in the world. And, both figures achieve great victories despite great hardship. To use a modern analogy to explain how Psalm 22 and the crucifixion narratives relate, my family once took our kids to see the Disney movie “Aladdin.” We loved it, but our older son, a real movie buff, laughed and hooted far more than I did. Later he explained why: he noticed how the movie weaved in motifs from other classic movies of the past.

Likewise, Psalm 22 offers an old classic movie, the crucifixion narratives a more recent one. People familiar with both easily sense the parallels between the two dramas since both portray analogous situations.

That’s why (and how) we can preach from Psalm 22 about Good Friday.

Digging Deeper

As I read and pondered, the psalm’s words and contents gripped me. I began to feel the speaker’s emotional crisis.

Phrases such as “abandoned,” “far from,” and “you do not answer,” (verses 1-2) voice the speaker’s incredible, excruciating relational alienation.

References to “womb,” “mother’s breast,” and “birth” (verses 9-10) attest to the tenderness of the relationship (which is now estranged), its life-long length, and how painful the breach feels.

Passionate pleas for a renewal of closeness (“Don’t keep your distance!” [verse 19]) and for rescue (verses 20-21) echo the agony of alienation.

Reference to the ancestors’ trust and experience (verses 4-5) bespeak the shock he’s suffering. Life with God isn’t supposed to be this way!

The mocking ridicule (verses 7-8), sarcasm (verse 8), and encircling enemies (verses 16-18) mean the speaker has no supportive human community.

Physiological symptoms (verses 14-15, 16b) mirror the crisis’ physical toll on him. He is totally exhausted.

The psalm’s first words, “My god, my god, why have you forsaken me?” (verse 1), are Jesus’ final words (in Matthew and Mark). They mark the climax of those Gospel reports.

The bottom line: this person is totally alone. His usual communities — with God and with humans — are gone. The former is totally silent and keeps his distance; the latter surround him with threats and taunts.

Based on these observations, three possible themes to develop or include in a sermon emerge. I hear their echoes throughout the psalm. Homiletically, I might call them “faint, familiar echoes worth remembering.” Or, put differently: if the crucifixion narratives are a DVD, Psalm 22 provides the director’s commentary.

First, there is the total bill due for our sins. We experience alienation from God and from each other, desperate loneliness, and physical despair.

Second, there is the total bill paid for our sins. Into this category goes our incredible suffering and our undeserved public humiliation. I might term it a “living death,” even a “living Hell.”

Third is the unbelievable depth of love for the world shown by the Father and the Son.

Lastly, there is one large irony. Psalm 22 ends with rescue and victory (verses 22-30) and the crucifixion narratives report that same theme three days later. God snatches victory from the jaws of defeat and effects salvation for humanity. Now, the mocking and ridicule sound foolish. The life surrendered becomes the life renewed. The true king still reigns, and the way is open for humans to conquer both sin and death.

April 2, 2010