Commentary on Hebrews 2:10-18

Much of our reflection about Christmas focuses on the who and the what. We ponder the roles of Mary and Joseph. We revisit Luke’s story of the shepherds at the manger in the city of David. We tell Matthew’s account of the magi before Herod in Jerusalem one more time.

But this season also leads us beyond the who and the what to contemplate why Christmas matters. This epistle reading for the first Sunday of Christmas offers preachers the opportunity to reflect on the purpose of the Incarnation, as the author of Hebrews sketches several reasons why Jesus came. After a prologue that sets out the superiority of God’s speech through the Son (1:1-4), Hebrews compares the Son and the angels (1:5-14) to stress the importance of what God has spoken in these last days (1:1; 2:1-4).

To support that claim, the author quotes and then interprets the Greek translation of Psalm 8:4-6. The Psalmist reflects on God’s mindfulness and care for human beings who live their mortal lives below the level of angels (2:7). But the author of Hebrews reads the psalm on two levels. Greek readers can interpret the phrases in 2:6 (literally “a human being” and “son of a human being”) either as an individual or as a group. Although English does not allow translators a straightforward way to preserve the richness of the Greek text, seeing these two levels of reading is key to understanding the author’s message. We consider each of these levels in turn.

The first level focuses on an individual “son of a human being.” The author of Hebrews initially reads the phrase “son of a human being” (New Revised Standard Version’s “mortals” in 2:6) in the singular, as a reference to the human Jesus. In the Synoptic Gospels, the title “Son of Man” was Jesus’ preferred way of referring to himself (Mark 2:10, 28; 8:31, 38). Focusing on the singular “Son of Man,” the author of Hebrews stresses that Jesus, once lower than the angels, is now “crowned with honor and glory” because of his suffering (2:9). This present vision of Jesus promises a future reign not yet seen.

But the author of Hebrews then shifts to a second level of interpretation, reading “son of a human being” as a collective term for all people. The New Revised Standard Version places this collective reading in the foreground in its translation, to stress that all human beings are the object of God’s mindfulness and care (2:8).

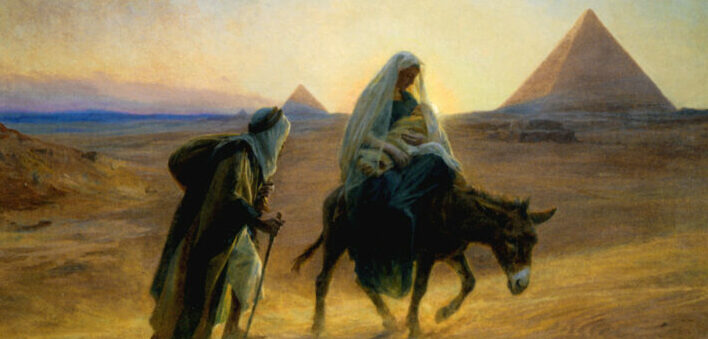

Both levels of interpretation become the focus of today’s text. The writer joins the destiny of Jesus, “the Son of Man,” to the destiny of all human beings (“mortals”). In that way, the goal of Jesus’ journey does not remain a solitary pilgrimage but becomes a path for the entire human family. Through this shared journey, God binds Jesus to his sisters and brothers, joining the one who makes people holy with those who are made holy (2:11). Just as human beings share in flesh and blood, in human frailty and mortality, so too does Jesus (2:14).

Here the author underscores one crucial grace of incarnation—that Jesus is with us as one of us, made human like us “in every respect” (2:17). He knows our lot from the inside, as one who becomes hungry and thirsty and tired. He knows joy and sorrow, delight and pain.

But the good news of incarnation is not simply that Jesus is with us as truly human. It is also that Jesus is for us. He has not come to help angels, but his fellow human beings, “the children of Abraham” (2:16).

For the author of Hebrews, that help comes in several forms. First, Jesus helps us in his role as the “pioneer of salvation” (2:10). This image is a rich one, depicting Jesus as our leader or captain or guide. He is the scout or trailblazer whose journey through life creates a path for his sisters and brothers to follow. To understand our human experience and the goal of our lives, we look to the humanity of Jesus. We follow where he leads. As our pioneer, Jesus experiences suffering, an especially important note for those who are facing testing. Because Jesus’ own path includes testing, he draws on his own experience to support others (2:10, 18).

Second, Jesus helps us because he frees us from slavery to the fear of death (2:15). He liberates us because he “destroyed the one who has the power of death, that is, the devil” (2:14). Ironically, that defeat comes through Jesus’ own death. Identifying fully with humanity in his own death, Jesus breaks the hold of death and the fear of death over humanity.

Third, Jesus helps us because he makes our communion with God possible. Here the author introduces the image that will dominate the rest of his sermon: Jesus as the “merciful and faithful high priest” (2:17). Through the “sacrifice of atonement,” Jesus opens up an access to God that had been closed off because of human sinfulness. Jesus restores our relationship with God, equipping us to draw near to God in worship. The “new and living way that he has opened for us” (10:20) gives us confidence to enter God’s sanctuary with confidence and assurance.

The author’s wide range of images here reminds us of the scope of the work of salvation that incarnation makes possible. In his mercy and in his faithfulness, Jesus becomes like us in every way and so provides help in times of testing. He claims us as his sisters and brothers, fellow pilgrims whom he frees from the power of death. As our high priest, he opens anew our access to fellowship with God. This range of imagery underscores that Jesus is both with us and for us. It provides a starting framework for our answer to the meaning of Christmas, leading us to the heart of this season’s celebration.

January 1, 2023