Commentary on Revelation 7:9-17

John’s apocalyptic visions in Revelation 7:9-17 present challenges in two different ways.1

The first challenge has to do with inclusivity/exclusivity. The second has to do with the social setting of the Apocalypse and how that translates to today.

144,000 or an Uncountable Multitude?

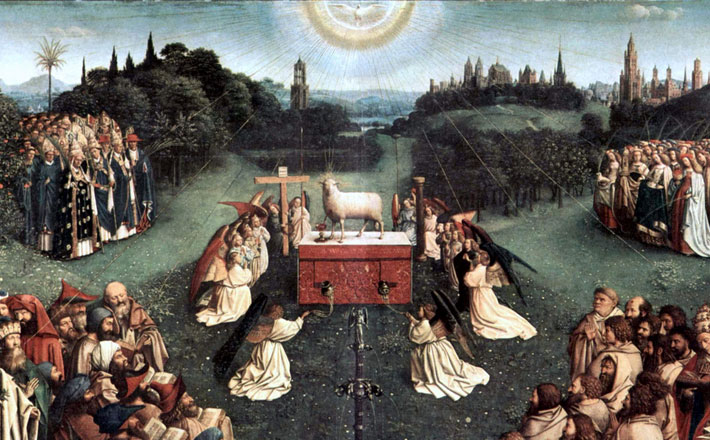

The first half of this text, verses 9-12, depicts an innumerable mass of people from every corner of the earth worshipping God. This opening vision evokes numerous biblical passages from both the Old Testament and New Testament. In a way similar to the story of Pentecost in the Acts of the Apostles, the multitude counterbalances the Tower of Babel story from Genesis 11.

The inclusion of all peoples (the Gentiles) in a vision of the eschaton (the end) was not uniformly accepted in all segments of Judaism. Some texts from Israel’s scriptures did, however, anticipate such a vision and understanding of the future (Isaiah 9:1-7; 60:1-7; Tobit 13:11-17). This diversity of perspectives within Judaism meant that such an inclusive vision of the eschaton constituted a challenge within early Christianity as well (cf. Luke 4:16-30; Paul’s opponents in Galatia). When discussing the issue of Jews and Gentiles in God’s plan of salvation, the Apostle Paul is forced, ultimately, to leave the details up to an inscrutable God (Romans 11:33).

The pressing interpretive problem with the eschatological vision in Revelation 7:9-13 arises when one notices the tension with the verses immediately preceding, which indicate that the number of people with the seal of the living God is limited to 144,000. When commentators approach this problem, they tend to resolve it by either positing that the 144,000 are simply a part of the greater multitude introduced in verse 9, or that there is a temporal distinction, i.e., that the 144,000 come prior to the fully eschatological vision of the end and the multitude in verse 9.

A second potential discrepancy between these two adjacent texts is that one seems a predominantly Jewish image, while the other is intentionally universal. Brian Blount, in a 2009 commentary, attempts to bridge this divide by making a argument that the image of the 144,000 is actually one of “eschatological imagining the universal church.”2 While there is some evidence to support such a conclusion, the imagery and language of 7:1-8 is decidedly more “Jewish” than what follows. It may be, however, that this juxtaposition might actually be the point the author intends.

Elsewhere in early Christianity, seemingly contradictory images or stories exist side by side, and only by their combination does one understand the point of the author. For example, the Gospel of Mark has two feeding stories. In one, 5,000 people are fed and 12 baskets are left over. In the other, 4,000 are fed and 7 baskets are left over. Mark used both of these stories symbolically to describe the inclusion of the Gentiles into the plan of God.

John may have the same intention for his apocalypse here. The juxtaposition of the exclusive report of the sealing of the 144,000 against the inclusive vision of a vast multitude from all corners of the earth is quite striking. John is interested in continuity with the past (he labels his work as “prophecy” and infuses much of what he does with imagery from Israel’s scriptures). At the same time, a definitive revelation has been given, providing a glimpse of the future that is built upon the past, but one that carves new channels for God’s activity and interaction with humanity.

Suffering then and now

The second half of this text, verses 13-17 also poses a challenge. As one of the elders answers his own question, we find out that the vast multitude in John’s vision are those who have come out of the “great ordeal; they have washed their robes and made them white in the blood of the Lamb.” In the future they will no longer hunger, thirst, or be afflicted; their every tear will be wiped away. On the face of it, this sounds quite nice. It is a place where one could easily read him or herself into the story — a vision of the future, perhaps conflated with heaven, in which every manner of thing will be well.

The problem is that the references to the white robes and washing in the blood are ciphers throughout the Apocalypse for the socio-historical setting of John’s community. The great ordeal (verse 14) clearly presupposes earlier portions of the Apocalypse (e.g., 6:1-8). Some of this trouble is also incipient in the letters to the churches (e.g., 2:2-7; 2:9-11; esp. 2:13). The Apocalypse was clearly written in a situation of oppression and suffering. The phenomenon of the emperor cult seems to have posed a significant challenge for those in John’s community, to the point that some have given their lives (2:13).

This poses a significant point of dissimilarity between the ancient and modern contexts (which is always the case when reading scripture). While there are Christians in parts of the world today that are facing serious persecution, I suspect neither they nor their pastors have time to peruse WorkingPreacher.org. How one translates the ancient context of persecution into the generally comfortable lives of many modern day Christians comprises the great challenge of preaching from the Apocalypse, (or many other parts of the New Testament).

One major observation may be helpful in this dilemma: Nowhere does John advocate that one seek out suffering. He never suggests that suffering is a necessary prerequisite of joining the multitude. What this text does testify to, however, is God’s response to the human predicament. Humans are not abandoned. The multitude worships God because they “came out” of the great ordeal. God will shelter them and wipe away every tear. The situation that John describes, and the one underlying his imagery — the suffering of his community — depends upon God’s response.

1 This commentary was first published on the site on Nov. 1, 2011.

2 Brian K. Blount, Revelation: A Commentary (The New Testament Library; Louisville: Westminster/John Knox press, 2009), 147.

November 5, 2017