Commentary on Matthew 21:1-17

After ministry in Galilee (4:17—20:34), Matthew’s Jesus enters Jerusalem.

He has announced multiple times that he will go to Jerusalem, the center of provincial Judean power (16:21; 17:22-23; 20:17-19). There the Rome-sanctioned and allied provincial leadership, led by the Roman governor, crucify him as an unsanctioned king of the Jews.

The conflict is not with all Jews. Jesus is a Jew and has Jewish followers. He conflicts with the Jerusalem elite. The conflict runs along lines of power and powerlessness, and societal differences between elites and a Galilean non-elite.

In entering Jerusalem, Matthew’s Jesus ramps up the conflict:

- He exercises kingly authority in procuring property (Matthew 21:1-7).

- He executes an entry ritual usually reserved for elite ruling figures (21:8-11).

- He attacks the Rome-sanctioned, temple-based rulers (21:12-17).

These imperially-imitative actions present Matthew’s Jesus imitating and asserting the ruling power and authority of Rome’s sanctioned elite agents.

Jesus initiates the first action from Mount Zion (Matthew 21:1). This location evokes expectations from Zechariah 9-14 of a battle in which God, the divine warrior and king, conquers all the nations hostile to Israel. Post-70, evoking Zechariah 9-14 envisions divine retribution on Rome for destroying Jerusalem and the temple in 70 CE.

Jesus sends two followers to claim a donkey and colt (Matthew 21:2-7). This action displays Jesus’ kingly authority:

- He orders two subordinates to procure the donkey and colt (Matthew 21:2).

- He foresees and addresses a possible objection (21:3).

- He exercises authority over people and animals (21:1-3).

- His disciples obey (21:6).

- The situation unfolds as he anticipated it (21:6-7).

This action enacts the imperial practice of angareia. Roman imperial officials such as governors and military figures requisitioned labor, transport (animals, ships, carts), supplies, and lodging from subject people. Subjugated peoples deeply resented the seizing of property and labor, and the arrogance of power that it expressed.

Jesus employs the practice. The animals’ owner is invisible. Jesus does not return the donkey to the owner.

Twice the Gospel refers to this exploitative and oppressive practice of forced labor, carrying a soldier’s pack (Matthew 5:41) and carrying the cross of a convicted criminal (27:32).

Verse 5 pauses the narrative to identify Jesus’ entry with that of a king exercising eschatological authority on behalf of God. It cites Zechariah 9:9 which celebrates God’s defeat of the nations who are Israel’s enemies, and the subsequent establishment of God’s reign .

In the context of the post-70 CE Roman-dominated world, evoking Zechariah anticipates the future divine victory over Rome. In the Gospel’s perspective, Rome’s power is not absolute nor final. God’s victory is under way, portended, but not yet accomplished, in Jesus’ activity.

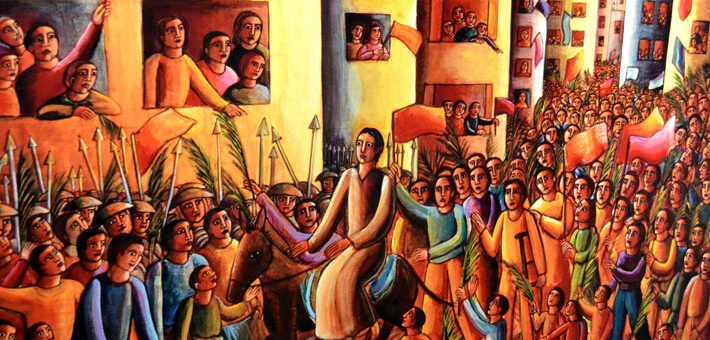

Verses 8-11 narrate Jesus’ second authoritative action, his entry to Jerusalem.

Ancient literature narrates numerous scenes whereby ruling elite figures—emperors, governors, kings, military generals—ceremonially enter a city. This entry ritual comprised:

- a previous military victory

- honoring an elevated figure

- crowds who welcome and acclaim the figure’s greatness

- a religious ceremony

- a speech of welcome.

This ritual displayed central Roman values: imperial greatness; supremacy over enemies; military domination and conquest; “power over” as the basis of societal interactions; courage in battle; violence, submission, enslavement, and subjugation of the enemy.

This spectacle or theater functioned to intimidate subordinates and exhibit the sanction of their gods for a world of hierarchy and domination.

Jesus’ entry imitates this elite practice. A crowd hails him as king. They spread cloaks on the ground and wave branches. They chant Psalm 118:25 which praises God for victory over the nations. He goes to the temple (Matthew 21:8-11).

Yet there are significant differences. Jesus rides not a war horse but an everyday beast of burden. Crowds of common folks welcome him. There are no speeches of welcome from elite leaders. He is not an elite figure. He is not authorized by the dominant ruling power. He represents God’s purposes, not Rome’s.

However, imitation coexists with resistance. Jesus anticipates future greatness in signifying God’s dominating, coming rule that will end Rome’s empire. The divine purposes are imperial.

Jesus’ third action is to go to the temple (Matthew 21:12-17). Since the Gospel is written post 70 CE, the scene explains the Roman destruction of Jerusalem and the temple as divine punishment on the unfaithful temple-based leadership.

Jesus’ first act drives out those who were selling and buying (Matthew 21:12). People bought sacrifices, while the temple treasury oversaw a massive temple economy involving various supplies for the temple’s functioning. They also collected the temple tax and functioned as a bank. Under Roman supervision, allied elite agents profited from this activity.

Jesus’ second act overturns the tables of the money changers and sellers of doves/pigeons (Matthew 21:12b). The act is symbolic, not a lasting reform. It highlights and protests the temple economy as sustaining the temple leadership’s vast socio-political reach that maintains an elite-benefitting society.

Jesus’ third act interprets these prior actions. He cites two intertexts. The texts offer contrasting visions of the temple and the societal structures and practices in which it participates.

The first evokes Isaiah 56’s vision of an inclusive society which includes even the eunuch and foreigner. The temple fails to function as a house of prayer for all people.

The second text evokes Jeremiah’s temple sermon that attacks social injustices and oppression while maintaining false confidence in the temple. Matthew’s Jesus accuses the temple leaders of making the temple a den or hideout for terrorists (Matthew 21:13b). The Greek term designates bandits or terrorists who destabilized imperial society by attacking elite personnel and property. The citation identifies the elite temple-based leaders as terrorists who cause societal damage by their practices. As in Babylon’s destruction of the Jerusalem temple in 587 BCE, the temple is said to be destroyed in 70 CE because of the leadership’s unjust societal vision and practices.

The scene closes with Jesus’ fourth temple action. He heals the blind and the lame as an act of repairing somatic damage caused by imperial practices. The children are delighted; the temple leaders are not (21:14-16).

PRAYER OF THE DAY

Righteous God, you brought your son Jesus into Jerusalem to show people the radical grace of your love. Show us this grace, and give us eyes to see your goodness. We pray these things in the name of Jesus Christ, our Savior and Lord. Amen.

HYMNS

All glory, laud, and honor ELW 344, H82 154, 155, UMH 280, NCH 216, 217

Prepare the royal highway ELW 264

Give me Jesus ELW 770

CHORAL

Hosanna to the Son of David, Dan Schutte

April 2, 2023