Commentary on 1 Kings 3:4-9 [10-15] 16-28

The passage begins with Solomon’s sacrifice to the LORD at the sanctuary at Gibeon and Solomon’s testimony to the LORD’s steadfast love (ḥesed) to his father King David. The reference to a “son to sit on his [David’s] throne” ties this passage to the covenant in 2 Samuel 7 in which God promises to “raise up” David’s “offspring” and “establish the throne of his kingdom forever” (verses 12-13). The history of succession, including the violent deaths of Solomon’s older brothers Amnon and Absalom, and the intercession of Solomon’s mother Bathsheba in securing Solomon’s appointment as successor ahead of his older brother Adonijah (1 Kings 1), are not referenced.

Solomon prays for “an understanding mind to govern your people, able to discern between good and evil” (3:9). The narrative of the two women seems designed to demonstrate Solomon’s “understanding mind” and “[ability] to discern between good and evil” (verse 9), underscoring the royal credentials of Solomon and the divine favor that accompanies him in carrying out his duties.

The fuller biblical account of Solomon’s reign hails his wisdom and devotion, while also laying bare the ways his consumption and empire building advanced his interests over those of the nation (1 Kings 4:22-23, 26-28; 5:13-16; 10:14-22), and that his divine loyalty was not singular (1 Kings 11:1-8). Solomon experienced divine favor and divine judgment (1 Kings 11:9-13). Solomon provides a lens into the faithfulness of God that is not simply contingent upon human “righteousness,” and “uprightness of heart” (verse 3:6). 1 Kings 3 is structured to communicate divine involvement in Solomonic rule with the goal of justice for “All Israel” (3:28).

This could be a good place to pause and reflect on the hopes and expectations for leadership prompted by Solomon’s prayer for “an understanding mind to govern your people” (3:9). What kind of leadership do God’s people deserve? Who and what needs attention? What leadership expectations are addressed and what are not addressed in 1 Kings 3? What are our contemporary hopes and expectations for civic leaders and civic life?

In the Bible, one measure of justice in the land is how the most vulnerable in society are treated, typically “the alien, the orphan, and the widow” (for example, Deuteronomy 24:17-22), following the example of God “mighty and awesome … who executes justice for the orphan and the widow, and who loves the strangers” (Deuteronomy 10:17-18). The 1 Kings 3 narrative introduces “two women who were prostitutes” (3:16), both new mothers, residing together in the same house. The women are clearly on their own, fending for themselves economically, each with a new human being to care for.

In Joshua 2, the prostitute Rahab provided shelter for the Israelite spies. Rahab is identified as “a woman, a prostitute” (2:1). In 1 Kings 3, the women do not have names, but they are similarly identified as “two women, prostitutes.” The text invites the reader to identify them by their humanity (as women) ahead of their circumstances (as prostitutes). This may be challenging because of the moral judgment and dismissal that are often triggered by the term “prostitute” and the use of such language in the prophetic condemnations addressed to Israel before its fall to the Assyrians (for example, Hosea 4:12) and to Judah before its fall to the Babylonians (Jeremiah 2:20). In 1 Kings 3, “prostitute” appears to be descriptive of their circumstances, not a moral judgment against the women. Moreover, the focus is on the king’s responsibility for delivering justice to these women.

If one measure of justice in society is the well-being of the most vulnerable, this might be a point to pause and ponder cracks and blind spots in civic policy and practice. What are the circumstances of their lives? Do these women point to other marginalized and vulnerable individuals and groups? The biblical prophets denounce rulers and citizens alike for ignoring those in need and tolerating social and economic inequities (for example, Isaiah 1:21-23; Jeremiah 5:23-31). If these two women are one illustration of the need for “an understanding mind to govern [God’s] people” (3:9), what are other conditions needing understanding for there to be just governance for “all Israel”?

In contrast to Rahab, whose household included “her father and mother and brothers” (Joshua 6:23), an infant is the only family each woman appears to have. The two women, with sons born three days apart, are the only people in the house (the absence of other persons is underscored several times in 3:18). Each infant sleeps alongside their mother at night. This intimacy of motherly care and the parallels between the two women are disrupted by the death of one of the infants.

The details of what happened—or might have happened—emerge in the appeal of “one woman” directly to Solomon, and the denial raised by the “other woman.” In her appeal, the “one woman” refers to the “other woman” as “this woman.” The “one woman” asserts that “this woman”

- lay on her own infant son during the night and he died

- placed her dead son at the breast of the “one woman”

- and took the “one woman’s” living son.

The “one woman” said she realized when she woke in the morning that the dead child at her breast was not her own child. The “other woman” (“this woman”) asserts “the living son is mine” (3:22). To which the “first” replies, “No the dead son is yours, and the living son is mine.”

The dialogue makes it difficult to distinguish “one woman” from the “other woman.” Perhaps by this readers are prodded to continue considering their shared humanity—neither woman wanting to face the loss of her child. The two women are divided over who is the mother of the living child, but both must be experiencing grief and anxiety, with no one standing alongside in compassion and with counsel befitting their particular situation.

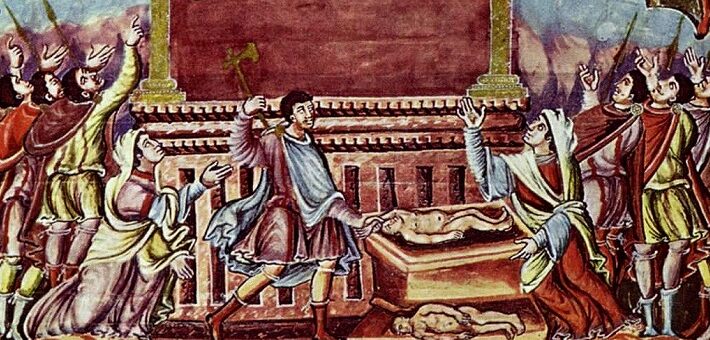

Solomon pits the two women against each other in their grief and anxiety in his command to “divide the living boy in two” (3:26). Solomon’s command triggers a gut-wrenching emotional eruption in one of the women. The narrator identifies her to readers as “the woman whose son was alive.” Which of the women arguing before Solomon she is, is not clear. This woman instructs Solomon to “give [the other woman] the living boy,” and “certainly do not kill him!” (3:26). Solomon’s “judgment” is in response to this woman’s petition (3:27).

Which woman is the mother of the living son? Is she the “one woman” who opened her petition to the king with the words “Please, my lord” (3:17); or the “other woman” who cries out “Not so!” (3:22)? Readers and commentators throughout the centuries have made arguments for each, as well as for the impossibility of deciding. (In the NRSV translation, Solomon instructs the living child to be given to “the first woman” (3:28), but the Hebrew says “give her the living child … She is his mother.”1) Only the characters present in the text to witness who speaks know which mother is which.

It is tempting to contrast and pass judgment on the mothers: viewing one as caring and the other as careless. Both infants were sleeping alongside their mothers. One son may have died because “this woman….lay on him” (3:19).

The women disappear from the narrative just as Solomon’s success in judging the case is heralded. Judgment has been rendered, but is that sufficient to claim that justice has been done? What lies before each of these women as they leave their audience with the king? How might divine wisdom and justice lead beyond judgment? How might each of these women find emotional healing? How might leaders and the wider community advance social and economic equity that transforms the futures of these women and the surviving child? How might this text point readers to seek wisdom and pursue justice in the contemporary context?

Notes

- The mother is identified as the “first woman” in multiple English translations. See Ellen Van Wolde, “Who Guides Whom? Embeddedness and Perspective in Biblical Hebrew and in 1 Kings 3:16-28,” JBL 114.4 (1995): 638, n. 30, and Gary A. Rendsburg, “The Guilty Party in 1 Kings III 16-28,” Vetus Testamentum 48 (1998): 539.

PRAYER OF THE DAY

Generous God, you gave your servant Solomon wisdom so that he might govern your people well. Grant us your wisdom, so that we might perform our life’s duties with gratitude and wisdom. We pray these things in the name of Jesus Christ, our Savior and Lord. Amen.

HYMNS

God whose almighty word ELW 673

If you but trust in God to guide you ELW 769

Forgive our sins as we forgive ELW 605

CHORAL

Pater Noster, Igor Stravinsky

Our Father, Harry T. Burleigh

October 30, 2022