Commentary on Isaiah 11:1-10

Last Sunday, the passage from Isaiah portrayed the unlikely image of hope: soldiers melting down their weapons and reshaping them into agricultural tools to feed a starving nation. Those images arose from the military realities that the small nation of Judah suffered in the years during and after the Assyrian invasion that occurred during Isaiah’s lifetime.

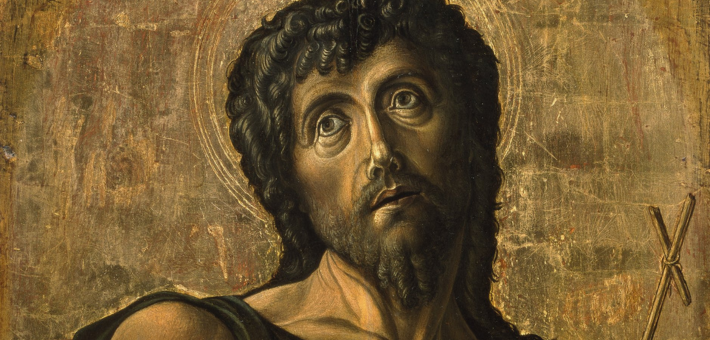

This Sunday, we get another stunning verbal painting stemming from the everyday lives of the ancient Judean communities. This time, instead of focusing on economic injustice, this vision imagines a world with a truly righteous ruler. In addition to plant imagery, the living creatures that surrounded them—both helpful and harmful—are added to the metaphor.

Isaiah 11:1–10 paints a picture of bounty and universal peace set against a background filled with smoke, fires, and blood. Whether this was a poem performed by the historical prophet, or a later reflection on this dark historical moment, the juxtaposition of dreams and nightmares results in the contrasting images of the text.

The poem begins with images of the budding plant life of spring. This metaphor elicits hope with its promise of a new beginning. The historical setting of the poem is far removed from such emotions, however. Isaiah prophesied during the period when the Assyrians destroyed the northern tribes of Israel. Israel was an agricultural and political area far more fertile and therefore fortified than the southern tribe of Judah. After the destruction of these northern tribes, the Assyrians marched south and besieged Jerusalem, the capital and sacred center of the southern kingdom.

The audience of Isaiah 11 is supposed to imagine the poem as recited, or perhaps even sung, to those inside a walled city, surrounded by a large army ready to invade, kill, and enslave Isaiah’s audience.

Perhaps the most graphic images are those of various animals, from predators to prey, in verses 6–8. The human audience looks on from afar at wolves and lambs, bears and cows, but the final pair hits home: babies and poisonous snakes living in close contact. Snakes, whether outside the city in the wilderness or inside one’s home, threatened the lives of the smallest and weakest humans. The pairing starts with a weaned child—in other words, one about four or five years old, who knows better than to play outside the city walls. This child’s activities are completely natural and innocent: playing, unaware of the threat that looms nearby. The second half intensifies the contrast, with the agentless baby or toddler sticking their hand into a random hole.

These images engage the readers’ emotions, since childbirth was so precarious in ancient Israel. Between the trifecta of infant death, childhood disease, and maternal death, the ability to raise the next generation was always tenuous in this ancient culture. Threats came not just from invading armies, but also from predators in everyday life that fed off the livestock and their human caregivers, even in the best of times. The emotions engaged here are not the anger felt toward human enemies, but a mixture of futility, failure, and hopelessness by Judeans just trying to live their difficult lives. Asking them to imagine a world where lions lie down with baby calves is simply ridiculous.

But this ridiculousness asks us to reread the beginning of the poem: the idea of a political leader whose very being evokes justice, wisdom, and care for the weakest in the community. The imagined world is one where absolute power does not corrupt absolutely. The repetition of the word “spirit” depicts this ruler as innately wise and appropriately subordinate to God.

The English translation of verse 3a does not adequately capture the emotion of the verse. The word translated “delight” can also mean “relish” or “joyfully value.” The phrase “fear of the LORD” expresses the proper attitude toward a deity that is ineffable. The wisdom of this ideal ruler results in their treasuring God as something Other and Holy. How unlike many of the depictions of Judah’s kings in other parts of the Bible!

This piety is also not self-serving. Verses 3b–5 focus on the king’s primary duty: to ensure justice throughout their kingdom. In the laws of ancient Israel, only landowners had full access to the justice system, leaving the poor, disenfranchised, and non-Israelites—especially women in these categories—without legal protections. While Isaiah 2 focused on people’s need for sustenance, here the passage focuses on what have become basic human rights.

While any king would protect the rights of other elites, an ideal king extends that attitude toward everyone in the community. Those who oppose such equity and inclusion are here deemed “wicked.” The fact that this righteous rule results in a ridiculously altered natural world reflects a common trope in Near Eastern royal poetry.

It is difficult for Christians to hear this poem, especially during the season of Advent, and not think it celebrates the birth of Jesus. But it is important to remember that this yearning for a perfect world pre-dates and exists independently of the Christmas story. I think if people around the world were asked to draw a picture of a perfect world leader, that ruler would have many of these same attributes.

We all know that one’s town or home can either be a place of refuge or an inescapable torment, depending on how that city or household is run. This Advent, we are asked once again to imagine. Can we dare to imagine a rule so ideal that even the hierarchical paradigms within the natural world transform into a landscape where the most natural enemies in our cosmos delight in just being together? No wonder this poem came to represent our deepest Christmas wish.

December 7, 2025