Commentary on John 20:19-23

Two very different but influential figures in 20th century Christianity, Karl Barth and Billy Graham, both stated that the 20th century should be the century during which “the Holy Spirit is brought to prominence.”

The 20th century brought the advent of the Pentecostal movement, with its emphasis on the baptism of the Holy Spirit and on speaking in tongues. Despite the fact that this movement experienced notable growth, the Holy Spirit — the third person of the Trinity — continued to be neglected in 20th century Christianity.

This neglect in church history is demonstrated by the diminutive space that our historical creeds apportion for the Holy Spirit. The Belgian theologian, José Comblin, suggests that a possible reason for this invisibility is that the Spirit empowers individuals by creating egalitarian conditions often beneficial to marginalized communities (i.e., women, the poor, those living in fear, the illiterate), which is usually an undesirable prospect for the hierarchical structures of institutions such as the church itself. According to Comblin, the Holy Spirit can pose a threat to societal and ecclesial powers. It certainly challenges exalted traditions, such as apostolic succession, and its pseudo-doctrines within protestant traditions. The Spirit really shakes things up.1

When the structures are used for the inclusion of some and exclusion of others, the Spirit is able to make possible the inclusion of the formally excluded. The Spirit, for example, might facilitate calling many into ministries who had not received ministerial validation through the route of apostolic succession. Jesus told the Samaritan Woman in John 4:23: “But the hour is coming, and is now here, when the true worshipers will worship the Father in spirit and truth, for the Father seeks such as these to worship him.”

Jesus continues in John 4:24: “God is Spirit, and those who worship him must worship in spirit and truth.”

The traditional theological and cultural beliefs of orthodox Jewish teaching about Samaritans, and, we can deduce, the physical and geographical locations, institutions, theology and doctrine, will no longer have a hold on God. The ways of the past have been replaced by the Spirit, which is not and cannot be controlled or limited by human systems. In fact, the Spirit enabled Jesus to theologize with a “common” woman, and to experience a fruitful ecumenical moment as a result of that encounter. The Spirit moved Jesus and the Samaritan woman from patriarchal, ethnocentric and theological restrictions.

How did this affect the Jewish teachers of the time and the power they held as the gatekeepers of orthodoxy? What implications does this hold for us today?

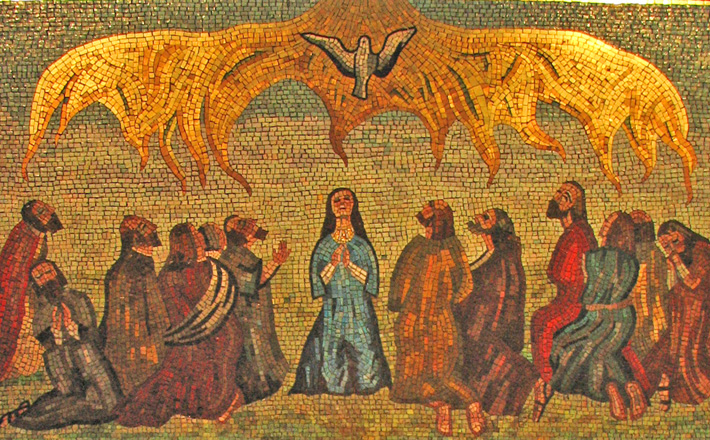

John makes it clear that after the crucifixion of Jesus, the disciples were overcome by fear and despair. This sentiment was to be expected from a group of individuals who had followed a charismatic leader — Jesus, whose ministry threatened the Roman Empire and the Jewish religious leadership. Consequently, those same disciples found themselves alone to cope with the religious-political consequences of Jesus’ three years of ministry and all of its challenges. They went from believing in the historical project of Jesus establishing the Kingdom on earth, to fearing a complete and utter failure of that trajectory.

Not surprisingly, Jesus came to visit his disciples, knowing that they would feel defeated and understanding the support they would need in order to move forward. He bestowed peace upon them, and they were overjoyed when he showed them his wounds. They, like Thomas, apparently needed physical proof of the resurrection.

Jesus’ return to visit with his disciples appears to have had a clear mission of fortifying them to continue his work. First of all, they would need peace to counter the turbulence of his death, and secondly, they needed evidence of his resurrection to restore their faith. Jesus dealt with these two pressing issues immediately. He did not simply return to celebrate his resurrection, but to prepare them as he sent them forth to continue the work he had begun.

However, how can people who witnessed total defeat and who were consequently living in fear, regain their faith with just a few words? Can one sermon, no matter how persuasive, change the minds, values and beliefs of a group of people? Can words create courage and faith where there is none? Before he left his disciples, Jesus bestowed upon them the Spirit. It seems that without the Spirit’s involvement in the lives of the disciples, there would be no peace, faith, or courage. This passage reminds me of Luther’s notion of the crucial role that the Spirit plays in breaking the barriers of sin and its bondage of the human will.

For Luther, human beings are, in and of themselves, incapable of living up to what God desires. The Holy Spirit makes it possible for the disciples, and for all of us, to be who Jesus wants us to be. The church needs to re-emphasize pneumatology, as declared by Barth and Graham. The role of the Holy Spirit as empowerment for ministry must be explored.

The Spirit is needed to help the church break through the barriers of ethnicity, sex, gender, race, class, ability, etc., and must be sought. We are living through a time in which there are so many challenges in our world, a time in which the fearless prophetic voice of the church is desperately needed. This prophetic voice can only be propelled by the empowerment of the Holy Spirit.

Notes:

1. Comblin, José. The Holy Spirit and Liberation. Theology and Liberation Series. Maryknoll, N.Y.: Orbis Books, 1989.

June 4, 2017