Commentary on John 21:1-19

When I saw him, his jet-black hair coiffed, swooped up and slicked up, the dark glasses, white leather jacket with tassels and beads, largish belt buckle, turquoise, and all the rest, I just knew he had to be an Elvis impersonator.

So, naturally feeling as if I was in on the joke, I called out to him: “Hey Elvis! How’s it going with your hound dog?”

I thought he would laugh. Instead, he looked at me as if I were crazy.

My wife, who was with me at the time, hissed under her breath, “I don’t think he’s pretending to be Elvis!”

Maybe he really believed he was Elvis. Or perhaps that’s just the way he dressed, implausible as that may sound. My wife, of course, was right. I’ve seen him since, and he dresses that way all the time, almost as if in a permanent state of Elvis-hood. And still, even though I say nothing, every time I see him, part of me wants to say, “But you’re not Elvis, you understand that? You’re just not Elvis!”

That experience comes to mind as I read John 21:1-19, assigned for the Third Sunday of Easter (Year C). It purports to be John, but it’s not, not really. It has all the familiar swag, but it’s not quite the real thing. My instinct is to wrinkle my puritanical nose, as if I’ve found an unpleasant impostor, or a self-conscious poser.

According to Gerard S. Sloyan, the text is almost certainly a later addition, written in the Johannine tradition, but not in the hand of John.

Among other things, the last chapter of John seemed to be the last word. The Johannine ignition switched off . . . only to growl to life again with, “After these things Jesus showed himself again … ” (John 21:1a).

Some unfinished business, perhaps? Yes, according to Sloyan, some things needed tidying up. Sloyan wonders if the Johannine community was unsettled about how it had ended for Peter, the three denials still ringing loud in its collective memory. “What becomes of him? How is he restored into the community?”

Peter didn’t exactly make a very strong exit, did he? Maybe a little damage control is in order …

Perhaps another reason is to put down any docetic rumors regarding the resurrection: the Risen One shows the wounds on his body, roasts fish over a fire, eating with the disciples on the seashore.

Finally, maybe there were questions about the Beloved Disciple. There were rumors, apparently, that he might not die, but be taken straight up to heaven. And maybe there was a rivalry between the two, Peter and the Beloved Disciple: who was the greatest? We thought that question got settled before Jesus died, but perhaps it still had some traction in the community.1

Whoever penned this epilogue meant to address these concerns.

Enter the Johannine impersonator. Turns out, this impersonator is actually quite good, even convincing in his own way.

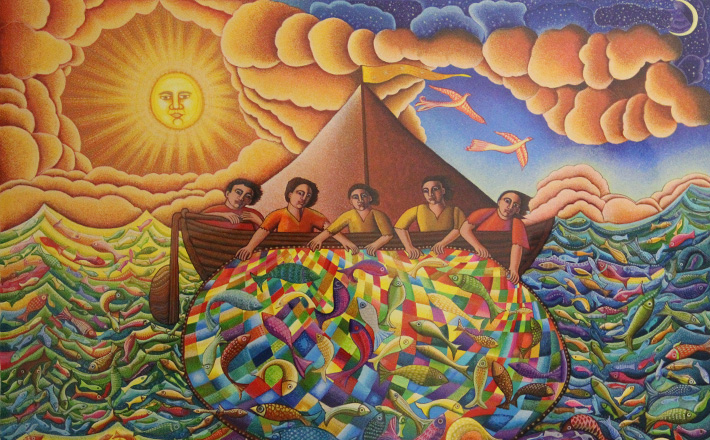

Simon Peter announces to the assembled disciples, “I’m going fishing.” Improbable as it may sound to our ears given all the goings on in this suddenly post-resurrection world, Simon Peter figured the fish would be biting and so, without a second thought, he collected his nets and gear. Out he went, and the others with him, to the Sea of Galilee. Seasoned with the sea, knowing the water and the currents like their own heart beat, they fished all night and still they caught nothing.

At dawn, they saw a stranger on the shoreline, but didn’t recognize him as Jesus, though Jesus knew them; this “stranger” called to them with a term of endearment, “children” (John 21:5b cf. 1 John), watching them as they plied their trade, one they had seemingly left behind. Then the stranger told them how to fish: “Throw your net out on the other side!”

They did so and they caught an enormous load of fish. Fish of all kinds. The symbolic significance of the number, one hundred fifty-three, is lost on modern readers, but the meaning of the story is not: the Jesus proclaimed by John draws (or drags) in an ecumenical collection, inclusive and diverse.

Moreover, it reprises two or three traditional stories of the disciples: the work of the disciples as fishermen; the more radical call to become fishers of people; and finally, the reminder of John’s Jesus that “apart from me you can do nothing” (John 21:15:5b); and it shares similarities with Luke’s account of the disciples “recognizing” the stranger/Resurrected One in their midst when he broke the bread.

In the final scene of this text, we hear the dramatic exchange between Jesus and Simon Peter. Three times Jesus asks Simon Peter, do you love me? The first time he asks, it’s a comparative, “do you love me more than these?” Most conclude that “these” refers to the other disciples, rather than the fishing gear or the fish. In any event, what is most important here is the way this text brims with symbols we have already seen: the charcoal fire burning in the background, its quiet red glow cast over the memory of Peter’s three-fold denial. Now it burns again, but this time what we hear is the confession, three times repeated, “Yes, Lord, you know that I love you.”

What sort of text is this? I’ve heard and, yes, probably given sermons on the significance assigned to the different words used for “love” in this text, but John may be using these terms interchangeably.2

Another possibility suggests itself when we think of this text as a “testing” narrative: Amid the memory of denial, Jesus “tests” the depth of Peter’s confession, almost as if he does not know Peter’s heart in the matter. This is baffling, hard to believe, even hurtful to Peter (John 21:17c), just as it would be to us: God knows all things, why should this be hidden from God?

Patrick D. Miller makes the intriguing argument from Psalm 139 that, indeed, God discerns who we are through just this kind of dialogue. Psalm 139 begins with the expansiveness of God’s knowledge: “You know my rising up and my lying down, before a word is on my tongue, you know it completely.” So we believe. But this truth exists in tension with the last verses of this beloved psalm: “Search me, O God, and know my heart; test me and know my thoughts” (Psalm 139:23). Miller points to the story of how the Lord tested Abraham and through that testing “knew” him: “ … for now I know that you fear God” (Genesis 22:12a).3

Impostor or the real thing? According to Sloyan, the center of gravity for this text appears in Jesus’ command, repeated twice: “Follow me” (John 21:19b, 22b).4

“The great matter,” according to Sloyan, “is to give the witness required: truthful, faithful witness. Not the lying witness of an inauthentic life but the Jesus-like testimony of a career . . . that is alethinos: genuine, real. True with the truth of God.”5

It is almost as if by deciding to follow Jesus, we return to our true selves, beloved of God. Our lives imitate Christ’s life, our joys Christ’s joy, our heartaches Christ’s heartache.

Feed my sheep.

Impostors? Posers?

Or authentically Jesus-like, “true with the truth of God,” always by the grace of God?

Notes:

1 Gerard S. Sloyan, “John” in Interpretation (Atlanta: John Knox Press, 1988), 227-230.

2 Sloyan, “John” in Interpretation, 230.

3 Patrick D. Miller, The Lord of the Psalms (Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press, 2013), 13-15.

4 Sloyan, “John” in Interpretation, 231.

5 Ibid., 232.

April 10, 2016