Commentary on Isaiah 52:13—53:12

On Good Friday, the most somber day of the year, why should we preach on the Old Testament text instead of the Gospel lesson?

We don’t spend enough time in the church reflecting on the crucifixion anyway. Why shortchange the one day when everyone expects us to talk explicitly about the crucifixion?

Despite the strength of the argument that we need to spend more time, not less, on the crucifixion itself, we should not neglect this rich, powerful, profound text. Focusing on the Old Testament reading can make our preaching theo-centric instead of christo-centric, but we affirm the consistency of God in proclaiming this text on Good Friday.

Even though our passage has many seeming parallels to Jesus’ experience, we should not see this passage as a “prediction” of Jesus’ passion. The prophet wrote to the people of his own time, presenting the “suffering servant” as a means of redemption for the experience of the exile. The early church looked to this passage to help them interpret the person and work of Jesus the Christ. We can look at it to interpret Christ and the ways of God.

The song begins in a way that might surprise us, with the affirmation of the exaltation of the servant. The servant shall “prosper,” be “exalted,” and “lifted up” (Isaiah 52:13). We are not quite sure what the prophet has in mind for this exaltation and success.

The root meaning of the first term, “prosper,” comes from the word for prudence and connotes things like military success (see 1 Samuel 18:15). The word for “exalted” is used in Isaiah 5:15-16 to contrast God with the humility of the people. We do not know exactly how the prophet thought this prosperity and exaltation would be worked out, but clearly the servant’s oppression and degradation would be vindicated.

Part of that vindication will be the recognition by political leaders of the integrity of the servant. Such leaders (in whose presence one did not speak until spoken to) would shut their mouths in the presence of the vindicated servant.

Christians look back at this passage through the lens of the New Testament and affirm that our suffering and obedience will be vindicated by God in the resurrection, even though that is not what the prophet was proclaiming. When we focus on the Old Testament reading, we can proclaim the ways God vindicates obedience now, as well as in the resurrection.

By beginning with the affirmation of God’s vindication, the prophet makes the theological point that God is acting within the suffering that subsequent verses describe. We may begin with the “happy ending” so we know on the front end that the suffering is not without purpose or meaning. But, this affirmation does not mean that God causes all suffering. Rather, God is working in all suffering.

The poem continues with a thorough description of the rejection, shame, isolation, and pain the servant endures. It includes two important theological points. First, the suffering is God’s act; it is a “perversion of justice” (53:8).And second, the servant suffers vicariously for the sins of the people.

Although some scholars claim that the suffering servant should be considered the whole people of Israel, the poet wants the readers to look on in awe and gratitude for what someone else has done on their behalf. This is not a poem that congratulates Israel on what it has accomplished. It is a poem that calls the readers to humble contrition, recognizing that someone else has done what they should have done.

This idea of vicarious suffering is complex and should not be oversimplified in our sermons. We often hear, for example, that Jesus died to satisfy God’s demand. This poem, the gospels and Paul are all clear that we did not offer up Jesus to placate an angry God. In a mysterious way that we cannot fully grasp, God worked through the servant, and through Jesus, for the redemption of humanity and all creation.

As 53:10 affirms, the experience of the servant was “the will of the Lord.” The servant modeled obedience where Israel failed. He bore the sins of the people. His obedience became a moral force. He made others righteous (53:11). He demonstrated that God rewards obedience, redeems suffering and vindicates those who endure.

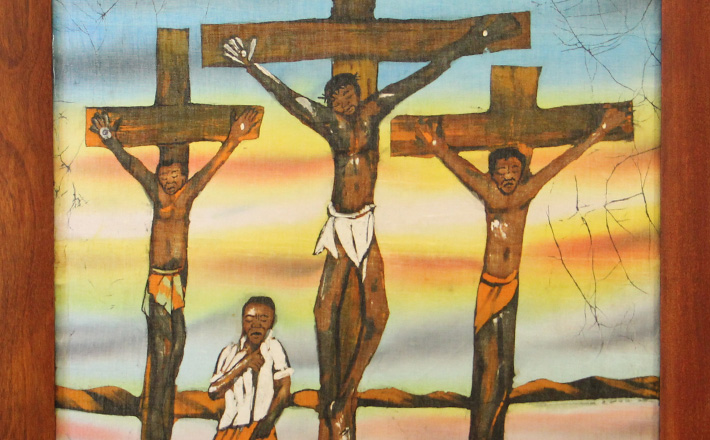

The value of proclaiming this passage on Good Friday is that it shows the consistency of God. The crucifixion of Jesus, though unique, was part of a pattern of redemptive suffering. The crucifixion is part of God’s way in the creation. God confronts evil with the obedient one, and through the obedience of the servant restores corrupt Israel to its rightful place.

One way to preach this passage is to affirm that God has acted over and over through those who obediently choose vicarious suffering, not as devaluation, but as courage in the face of the world’s evil.

The suffering servant chose obedience to redeem the people of Judah. Christ chose obedience to break the powers and principalities. Contemporary servants such as Oscar Romero and Martin Luther King, Jr. faced persecution and death but refused to back down. They unleashed a moral force into the world.

Our proper response is gratitude for the courage of those who have obeyed. We benefit from their courage. Their experiences teach us about the depth of evil in the world, but also about the lengths to which God will go to redeem the corrupt creation.

Let us trust God’s vindication.

April 10, 2009