Commentary on Exodus 12:1-4 [5-10] 11-14

In the story of the Exodus out of Egypt, this lesson is key.

It marks the place in the story where God begins to act decisively. Even though God has already brought nine plagues upon Egypt, nothing has changed for the Israelites to this point: they are still in Egypt, in bondage. According to the immediately preceding chapter 11, God directed Moses to tell the Israelites to get ready. The next visitation upon Egypt, God said, will be different from all the previous plagues, because this time the result will be freedom from Pharaoh and departure from Egypt.

The importance of this turning point is underscored by a detail in the lesson we usually skip over: God says that this month in which the Passover deliverance event takes place, from now on, is to be the beginning of the calendar year for the Israelites.

In the Abrahamic faiths, chronological reckoning begins from what is considered the decisive point in history after which nothing remains the same. In Christendom, calendar-reckoning begins with the birth of Christ; in the Islamic world it begins with the Hijra, Muhammed’s flight from Mecca to Medina; in Judaism it begins here, at the deliverance out of Egypt. In all three cases, chronological reckoning began at that point where God was perceived to begin creating a community of redemption.

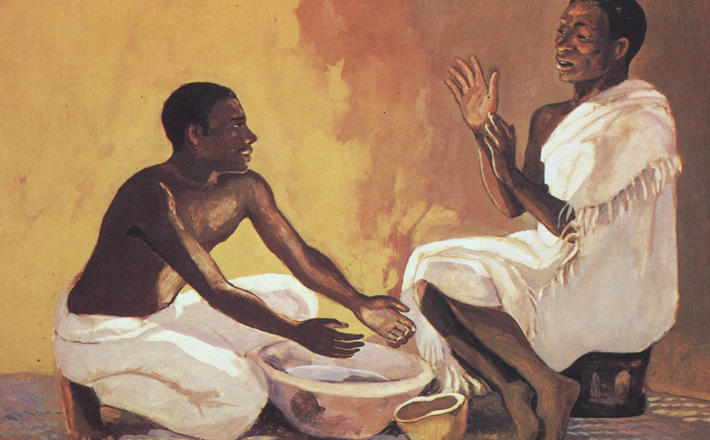

In the case of Moses and the Israelites, our lesson spotlights that moment when God began to shape the Israelites into a community by an act of redemption. In the preceding chapters God had spoken through Moses against the enslavement of the Israelites under the political regime of Egypt.

Now, this decisive act of deliverance will testify to the God of Israel as the supreme divine power active in this world, because this is the only God who acts on behalf of the enslaved and the oppressed. None of the gods of Egypt can prevent this from happening (“on all the gods of Egypt I will execute judgments”). They were divine sponsors of the oppression, yet they are powerless before the true God.

Note: according to our lesson, it is not merely God’s action against the Egyptian system of oppression that forms the community of Israel. In addition to experiencing God’s redemption, Israel becomes the people of God also by remembering it, by memorializing it.

God tells Moses here to instruct the Israelites to mark the beginning of their history as the people of God by coming together in communion over a memorial meal (verse 14 — “it is a zikkaron,” memorial). Why a zikkaron “throughout your generations”? It is not as though the Israelites who themselves experienced this deliverance would have any trouble remembering it.

Rather, a memorial ritual is for the sake of later generations who were not there to personally experience the transformation from slavery to freedom, from death to life. Hundreds, even thousands of years later, the ritual actions and the recited words bring the ritual celebrants back to that moment of deliverance. That moment long ago when we were slaves in the land of Egypt, and the Lord delivered us with a mighty hand. In that ritual remembrance, time and space dissolve just for a moment. All God’s people are united in the memory of what God did on behalf of everyone against the gods of slavery and oppression.

The Gospel record conspicuously associates the death of Jesus with this Passover memorial. In the New Covenant way of memorializing, the death of Jesus is woven into the memory of divine action bringing deliverance. And, like in Egypt, we exist in this world as the people of God not solely by virtue of the death of Jesus, but also in our remembering of it.

Like the Jewish Passover, the ritual words and actions of Christian Eucharist bring celebrants, even thousands of years later, back through space and time to that moment where God acted on behalf of our redemption from death. That’s why, in reporting what Jesus told his disciples, “Do this in remembrance of me” (Luke 22:19), the Gospel record uses a Greek word in the same semantic field as the Septuagint translation of Exodus 12.

Thanks to the power of that zikkaron, the atoning death of Jesus is for us no mere doctrine. Face-to-face with his tortured body and his shed blood, the reality of our own personal mortality is united with his, and we can be set free from our enslavement to the fear of death. But this deliverance remains real to us only as we are faithful to remember it together, as our lesson instructs.

March 24, 2016