Commentary on Lamentations 3:22-33

At first blush, it appears that the assigned text is a bold declaration of faith and hope in the midst of an unrelenting lamentation over the horrific events surrounding the siege and destruction of Jerusalem.

Indeed, that these verses serve as the only beacon of hope in the entire book is the judgment of a majority of commentators. S. Paul Re’mi’s remark on this passage is typical: “One individual, and only one, it seems, arises with a call of hope, of hope in the mercies of God. Thus, he appeals to his brethren to examine their ways and return to the Lord with all their heart.”1

If, however, these verses serve as the lighthouse of hope in Lamentations, it’s light burns neither bright nor long. As Iain Provan noted some years ago:

“The reader who reads the chapter to the end does not receive an impression of great hopefulness. Nor is the reader who reads the book to the end left with this impression of the book as a whole. Lamentations does not, after all, end with 3:21-27.”2

Resisting the trend to force the chapter (and the book) into an articulation of hope, Provan views chapter 3 as a poem that “is in reality a mixture of hope and despair, and it ends in a plea to God which leaves us balanced on a knife-edge between these two.”3

To the contrary, evidence within the text indicates that the impulse driving Lamentations 3:22-33 (and on to verse 39) is neither autobiographical nor pedagogical but is, instead, rhetorical. The expressions of hope and other pious sentiments that appear in verses 22 to 39 represents the poet’s desperate rhetorical strategy to coerce a response from Yahweh. These verses invoke a series of orthodox confessions and standard wisdom-like teachings that aim to leave the LORD without excuse and with no other option save to resolve the pain of the poet and Jerusalem.4

Ancient Israel’s faith life included a rich tradition whereby the integrity and character of God were held up as reasons for God to act on behalf of the petitioner. One thinks, for example, of Abraham’s intercession on behalf of the citizens of Sodom: “Shall not the Judge of all the earth do what is just?”[5] By acknowledging Yahweh’s sovereignty as Judge, Abraham circumscribes the range of Yahweh’s activities. Whatever else the Judge might do, he must act justly.

Psalm 89 provides another excellent example of orthodox praise employed as a vehicle for compelling the LORD to act. The praise of the LORD’s work in creation (verses 2 to 3) and of the Lord’s promises to David (verses 4 to 5) are expanded in verses 6 to 19 and 20 to 38, respectively. But the balance of the psalm consists of an unrelenting lament about the defeat of the Davidide. The psalmists’ questions to Yahweh are particularly poignant following the extended sections of praise. Considering Yahweh’s sovereignty over the cosmos and in light of Yahweh’s promises to David, what could Yahweh say to the questioning pleas of verses 47 to 49? What excuse could Yahweh offer to the accusation latent in verse 50?

Lord, where is your steadfast love of old,

which by your faithfulness you swore to David?

An identical rhetorical strategy appears in Lamentations 3. The poet’s lament in the first twenty verses pauses in verse 21 where he is resolved to “hope,” better translated as “cause myself to adopt an expectant attitude.”6

While he waits, however, the poet marshals a series of well-placed adjectives calculated to impel the LORD to act on his behalf. By characterizing the LORD as merciful and possessing steadfast love (verse 22) as well as faithful (verse 23), the poet evokes a “credo of adjectives”7 that intends to remind the LORD of God’s own identity and character. That is, this is a God who by God’s own nature has demonstrated these characteristics and who ought now, in the poet’s distress, act as his redeemer rather than as his enemy (see 3:1-19).

Verses 25 to 39 articulate traditional attitudes about suffering (and how one might cope with it) such as are found in Israel’s wisdom writings. Like the “comforters” of Job, this portion of the poem exhorts the sufferer to recognize that the LORD’s intentions are benevolent and that, in times of distress, the best course consists of waiting quietly for God’s salvation to arrive (vv. 25-30). It is not Yahweh’s will to reject or afflict (vv. 31-33) and God remains aware of suffering (vv. 34-36). Indeed, avers the poet, the Most High ordains all that happens, both good and bad (vv. 37-38). Therefore, one should not complain of suffering, as it surely must be a consequence of sin (v. 39).

These wisdom teachings articulate the conditions that, from the poet’s perspective, should exist but do not. The world should be one in which God “does not willingly afflict or grieve anyone” (verse 33), but it is not.

Once again, albeit launched from a different starting point in the theological tradition, the “stylized rhetoric of the God of fidelity”8 characteristic of verses 22 to 24 is evoked in verses 25 to 39 as well, albeit in the latter verses the rhetoric focuses on the faith claims articulated most often by Israel’s wisdom traditions. Both professions intend to motivate God to move and to save, the former on grounds of God’s own faithful character and the latter based on wisdom’s general confidence in God’s beneficent management of the world.

That God is not so moved to act remains a problem for the poet and the preacher. The brave words of faith soon dissolve into lament. The poem and the book end with divine silence.

The poet is left without answers, without a divine response — as often are we. This is why the preacher may do well to consider a sermon on the silence of God. What do we do, and how do we carry on in faith when platitudes ring hollow or when they taste like ashes in our mouths when we utter them? How different, after all, is the assertion of some divine albeit unknowable plan in the face of tragedy than the claims of verses 32 to 33? How do we persist in faith when pain continues unabated, when God does not answer, and we are left alone?

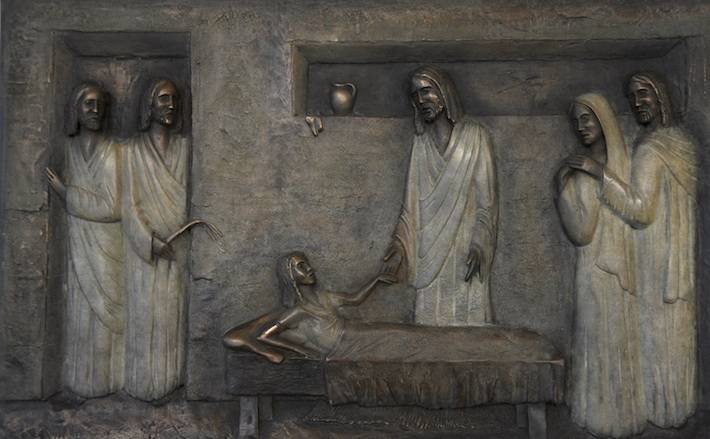

In the fullness of the Scripture, of course, we proclaim a God who knows the anguish that inspires lamentation. This God has suffered and taken death God into God’s own life. Moreover, we know through the resurrection of Christ that life, not lament, is God’s answer to our disappointment, pain, and despair.

But that is not yet. We do not yet experience the joy of resurrection; we have only its promise. We have faith, not certitude. The preacher should tell the truth about that. Tell that truth and the verity of this poet’s lamentation. His lament proceeds as lamentation does for all of us: a cry in the enveloping darkness, at the beginning of the watches (2:19) and continuing until we are met, at long last, with the joy of Easter dawn.

Notes:

1 S. Paul Re’mi, “The Theology of Hope: A Commentary on the Book of Lamentations,” in God’s People in Crisis (ed. Robert Martin-Achard and S. Paul Re’mi: ITC: Edinburgh: Handsel; Grand Rapids: Wm. B. Eerdmans, 1984), 76.

2 Iain W. Provan, Lamentations (NCB: Grand Rapids: Wm. B. Eerdmans, 1991), 22.

3 Provan, Lamentations, 22. Provan is followed by more recent commentators such as Adele Berlin, Lamentations: A Commentary (Louisville: Westminster John Knox, 2002), 86; F.W. Dobbs-Allsopp, “Tragedy, Tradition, and Theology in the Book of Lamentations,” JSOT 74 (1997), 48–50; and Kathleen M. O’Connor, The Book of Lamentations (NIB, 6:ed. Leander E. Keck: Nashville: Abingdon, 2001), 1051, 1057.

4 For a fuller treatment of this thesis, see Walter C. Bouzard, “Boxed by the Orthodox: The Function of Lamentations 3:22-39 in the Message of the Book.” In Why?… How Long? Studies on Voice(s) of Lamentation Rooted in Biblical Hebrew Poetry, edited by LeAnn Snow Flesher, Mark J. Boda, and Carol J. Dempsey (New York: T & T Clark, 2013), pp. 68-82.

5 Gen 18:25 (NRSV).

6 So C. Barth, TDOT 6, 55.

7 Walter Brueggemann, Theology of the Old Testament: Testimony, Dispute, Advocacy (Minneapolis: Augsburg Fortress, 1997), 213–28.

8 Brueggemann, Theology, 221.

June 28, 2015