Commentary on Isaiah 52:13—53:12

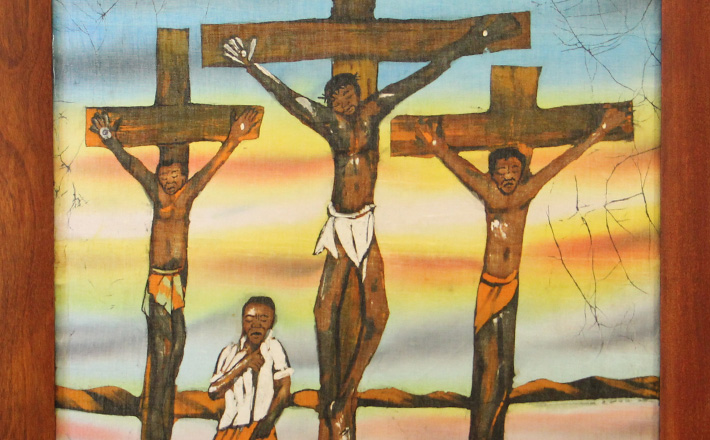

One of the most famous poems of Second Isaiah, Isaiah 52:13-53:12, depicts a human being, a servant of God, at what seems to be the very lowest point of his life.

Suffering horribly, he is isolated from the rest of the world, which views him with horror and keeps its distance. Everything is not as it seems, however. There is more going on here than meets the eye. Throughout the poem, the prophet invites the audience to view the suffering servant from various angles, creating a poem with a deep tension, a tension built on the contrast between the way things seem to be and the way they truly are.

When it was first written, this poem was most likely intended to inspire the people in exile to see their suffering as meaningful and to assure them that their vindication was near. Throughout the centuries, it has been a powerful word of comfort to many who have suffered in very different circumstances. The scholarship on Isaiah 53 is immense and reflects the powerful impression this poem has made on so many people and communities. For the purposes of this commentary, just two example of the ways in which the poem has inspired will have to suffice.

Scholars have noted that innocent suffering of the servant in Isaiah 40-55 appears to have been a part of the inspiration for the book of Job.1 Early Christians sought to understand and explain the suffering of Jesus through the lens of the suffering of the servant. Just these two examples of the afterlife of Isaiah 53 point to the fact that the words and themes of this poem are not easily forgotten or overlooked. They are haunting. Forceful.

The poem begins with a call to “See…” thus inviting readers to observe the drama as it unfolds. This first section of the poem is spoken by none other than God, who sets the stage for us, describing the upcoming exaltation of an individual called “my servant.” Isaiah uses the expression “my servant” to describe the people of Judah throughout Isaiah 40-55 (see last week’s Old Testament commentary for a more in-depth discussion of this designation for the people), and this phrase was a powerful reminder to the people in exile that, in spite of all appearances to the contrary, they belonged to God. They were servants of God, not Babylon. “My servant” connotes a divine purpose, points to a human being worthy of note, and God’s call in the opening verses of this poem to look at “my servant” leaves no room for readers to doubt the dignity and divine purpose of his life.

The appearance of the servant, however, plays with our expectations. While 52:13 suggests that we are about to witness the exaltation of a servant of God who has done well, verses 14-15 describe the physical appearance of the servant as almost sub-human, unworthy of note: “marred, beyond human semblance.” No one — not even the kings of the nations (52:15) — could have anticipated his exaltation, which leads us as readers to ask the same question with which the next part of the poem begins: “Who has believed what we have heard? And to whom has the arm of the Lord been revealed?” Already the audience is drawn in, compelled to look closer.

This part of the poem provides another perspective on the servant, the perspective of a first person plural: “we.” The identity of this group is unclear. Scholars have suggested the astonished nations and kings of 52:15 are speaking here, and this interpretation makes sense because the sentiments expressed in 53:1-3 are clearly connected with 52:15. It would be a mistake, however, to spend too much time on the issue of identity. The more interesting point is that the group speaking is a group of bystanders.

They are not, as far as they know, involved in the action. Watching from a safe distance, they marvel that God’s might is revealed in this inconsequential human being (verses 2-3). At this point in the poem, the servant stands alone, surrounded by these onlookers, but still isolated from them. The striking dichotomy between his appearance and his true identity is a source of wonder to them, but they are detached from him until the next movement of the poem delivers the most surprising insight into the servant so far.

Verse 4 begins: “Surely, he has borne our infirmities and carried our diseases…” and the relationship between the group of onlookers and the servant is utterly transformed. They entered the poem as a group of bystanders, but they are bystanders no more. They are bound up with the servant. Their fates depend upon his actions. Even as their description of his physical appearance grows more tortured — “wounded,” “crushed,” and covered in “bruises” (verse 5) — their awareness of his hidden strength and noble purpose grows. He has silently and willingly taken on all of this suffering on their behalf! Indeed, he is marred because he bears the very worst of them: their diseases, their sins! All that was unsightly about him belonged to them, and his disfigurement is part of a larger plan to make them whole. Now they can truly see him, and, in seeing him, they see themselves.

This is a powerful moment in the poem and, I would argue, it is a moment that is often misinterpreted when we try and place it within a theory of atonement. The poetry here is dense with allusion, sound play, and word play. It is richly suggestive and meaningful, but it is not interested in answering the hows and whys of vicarious suffering. It is interested in doing something to the reader. To the community in exile, it was attempting to transform their understanding of their calling in the world, to see their suffering as purposeful with the promise of survival and recognition at the end.

In the Christian tradition, we read this text on Good Friday, and I wonder what purpose it has there. What is this living word trying to do to us? I think it is very important when preaching this text to help our congregations see themselves as the bystanders of this poem, to find themselves struck by the awareness that all of this suffering is what “we” brought on another human being and to be amazed that Jesus willingly took on himself all of this suffering on our behalf.

The next step is to talk about the wide range of responses we might have to this moment of truth. We might be moved to gratitude for the sacrifice of Christ, which might be a good start, but it is only a start. Because to sit, transfixed, at the sight of someone suffering — whether on our behalf or not — is to remain bystanders. This poem demands that we do more than watch. If the servant of God is there in all of that suffering, then that is where we are supposed to be. Where anyone is suffering, that is where we are supposed to be.

1See, for example, Marvin H. Pope, Job, Anchor Bible Commentaries (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1965).

March 29, 2013