Commentary on Matthew 18:21-35

What might the practice of limitless forgiveness look like in a modern capitalist economy? Is it even possible?

The economy of forgiveness Jesus announces is congruent neither with the values and assumptions that govern human economies nor the relentless pursuit of power and privilege that drives our daily social relationships. The pursuit of unlimited forgiveness (Matthew 18:21-22) requires a definitive break from the tacit arrangements that govern everyday life, whether ancient or modern.

When Peter asks Jesus how many times he has to forgive a brother who sins repeatedly against him — as many as seven times? — Jesus explodes Peter’s magnanimous offer: not seven times, but seventy-seven times. Jesus’ number is not drawn from the air. It mirrors the boast of Cain’s descendant, Lamech, in Genesis 4:23-24, who brags that the mortal vengeance he has extracted against a young man who hurt him far exceeds God’s promise of seven-fold punishment against anyone who might kill Cain. Jesus is calling his community of disciples to participate in undoing the curse of Cain and Lamech that has kept their offspring trapped in spasms of envy, hatred, violence, and retribution across the generations to this day.

The parable of the unforgiving servant serves as a sobering counterpoint — a sharp warning — to those who might think forgiveness is possible on limited terms. The parable illustrates with painful clarity the difficulty of practicing forgiveness in a social system built for different purposes. It may also illustration the power of “binding and loosing” (Matthew 18:18): even heaven has a hard time undoing the damage wrought by human choices and the intractable systems we build to sustain our places in the world of Cain and Lamech.

Despite the suggestion at the end of the parable that God will act as the king in the parable does (Matthew 18:35), we should resist the inclination to read the parable as a simple allegory, in which the power figure, in this case a king, represents God, and the servant who is forgiven much but refuses to forgive another stands for Israel or some other too easily vilified social group. Parables work best when they are read primarily as simple, integral stories, rather than as ciphers to be decoded in terms favorable to Christians. In any case, parables do not usually convey a simple moral point so much as they are meant to induce critical reflection and to pull the blinders from our eyes.

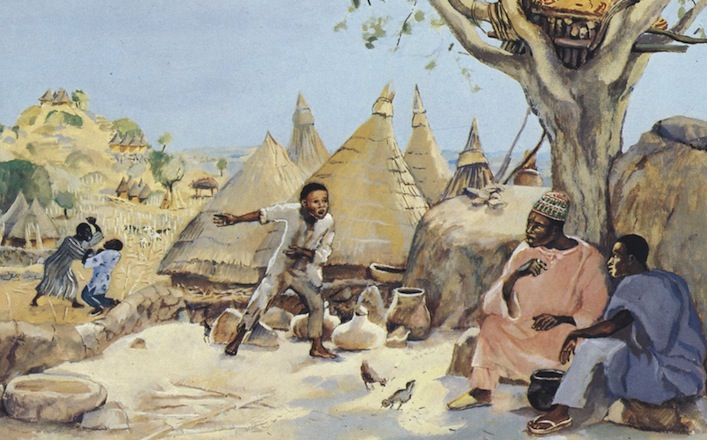

Although the figures in this parable are exaggerated, as so often in parables, the king and his slave represent and follow scripts that would have been familiar to ancient Mediterranean audiences. Kings used agents like the “unmerciful servant” to organize lower levels of agents, from tax-farmers to torturers (Matthew 18:34), who together made up a system that ensured the continuous flow of wealth, power, and honor to the top of the pyramid.

The unforgiving servant is apparently a manager of the highest level, effectively a CFO, with control over the movement of vast wealth. The astronomical “debt” or “loan” he owes may represent the income he is responsible for producing from those lower on the pyramid of patronage. In the Mediterranean economy, the goal was to pass a steady, acceptable flow of wealth further up the pyramid, while retaining as much as one could get away with for oneself, to be used to grease one’s own way further up the pyramid.

This slave, who works near or at the very top of the pyramid, may have taken too large a share for himself. The reckoning described early in the parable is meant to correct any wrongdoing on the part of the slave, but also to send a message to the whole system to limit such “honest graft.” In such a case, the only recourse on the servant’s part would be to beg for mercy, as this one does to good effect. Disciplining and then restoring such a slave might be a better move on the king’s part than finding a replacement. Although the king forgives the slave’s enormous “loan,” the slave’s obligation to the king is actually intensified. He is likely to be more loyal going forward than less.

The king’s stupendous act of mercy is, however, neither a private matter nor an act with consequences for this slave alone. Wiping this debt off the books has implications for everyone down the pyramid, a fact certainly noted by all the clients of this servant. The king effectively inaugurates a regime of financial amnesty, a jubilee, not only for one slave, but for everyone in his debt.

The economic revolution, however, makes it not much further than the door. The slave’s immediate encounter with one of his client-slaves, someone with a much smaller obligation, demonstrates that the forgiven slave intends to revert to business as usual. He gives no heed to the second slave’s appeal, although it is nearly identical to the one he had just given the king. His failure to carry on the forgiveness the king granted him not only halts the spread of financial amnesty in its tracks, it also mocks and dishonors the king himself. The king cannot ignore such an affront. The unforgiving slave binds himself not to the king’s mercy, but to the old system of wealth extraction and violence. He thus binds the king in turn to deal with him once again within the confines of this system.

Matthew’s Jesus seems to tell us that God’s forgiveness has necessary limits, but perhaps these are the limits we set. The unforgiving slave brings judgment on himself by treating his own forgiveness as a license to execute judgment on others. He thus transforms a merciful king into a vengeful judge. The problem lies not with the king, or even by analogy with God, but with the world the slave insists on constructing for himself, under which terms his fate is now set. With whom, and to what systems, do we bind ourselves each day?

September 17, 2017