Commentary on Matthew 18:21-35

Ask a child to apologize, to admit his or her wrong-doing, and you will discover the early limits of our empathy.

Being corrected is painful, for it brings to mind how we have failed, especially how we have let down those we love. Asking for forgiveness is an act of humility. And yet perhaps as challenging as asking for forgiveness is the granting of forgiveness. After all, forgiveness heals relationships by requiring us to let go, to turn the page, to refuse the right to hold on to bitterness and anger. Forgiveness, in short, sets things right again. Forgiveness is a powerfully healing force but also an incredibly difficult thing to receive or share.

Peter here asks about the limits of the granting of forgiveness even as Jesus brings our attention back to the grace under which God has healed us. Peter wonders aloud how far our forgiveness should expand. Jesus turns Peter’s question around to the deep grace God has shared.

The immediate, narrative context of Peter’s question is last week’s discussion around confronting disagreements in community and the (hopefully) rare necessity of excluding members of the community who pose a danger to the community’s integrity. We noted last week how easy it is for this process to become the focus of our attention rather than the values of love underwriting it. Additionally, we observed how easy it might be to manipulate Jesus’ teachings here, to turn them to my advantage instead of the needs of the community.

Peter thus asks how wide our forgiveness should be, how many times must I be slighted before I say enough, how long, O Lord, before our reservoir of grace can be exhausted. This is a natural question, of course. We know too well both the small and large ways that others can tread upon us. We know too well that others can take advantage of our generosity. We know too well the sting of consistent affront. At what point do we say, “Enough?”

Peter begins by establishing what he and we might consider a rather high bar of forgiveness, a significant concession to those who might hurt us. Should I forgive someone as many as seven times? That seems generous if not munificent. After all, aren’t second (let alone seventh!) chances exceedingly rare in our lives?

But Jesus, as he often does, poses a radical suggestion: not seven but 77 times are we to forgive. Of course, what Jesus is suggesting is not a larger ledger upon which we can keep track of offenses. He’s not merely requiring an additional number of gracious acts. Instead, he is suggesting there is no need for a ledger whatsoever. Forgiveness is a deep reservoir of grace that ought never to run dry. Why not?

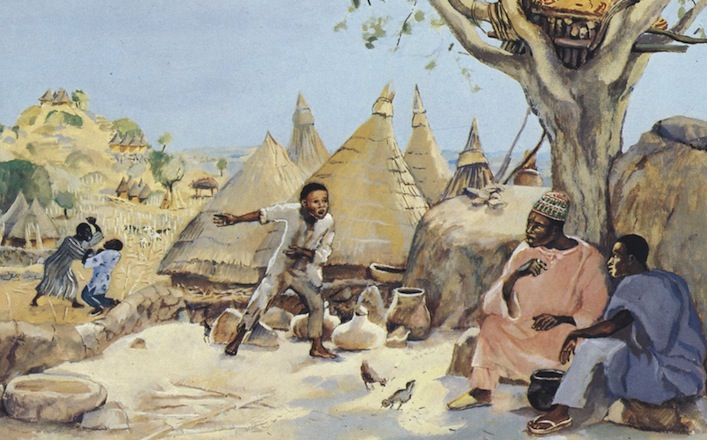

As we answer this question, we should note Jesus’ parabolic response. Jesus seems to treasure teaching in parables. He is a vivid storyteller. He casts simple but memorable stories that communicate profound and life-altering truths. This might explain the continued ubiquity in our culture of the images Jesus cast and the perpetuity of his teachings.

In this particular parable, Jesus tells of a king settling debts with his servants. It may be that the servants are in the state they are in precisely because of the burden of their debts. That is, they may be slaves as a way to compensate their aggrieved creditors. One of these servants carries a massive financial obligation to his king, a debt too great ever to be repaid. And so the king decrees that the nameless debtor and his family ought to be sold in order to pay the debt. If he will not receive the amount due, at least the king can receive some compensation in exchange for the slave’s labors.

Knowing his whole life was about to be crushed, the debtor begs for more time, more patience but receives something unexpected instead: a wholesale remission of his debts.

The motives of the king are simple: pity. Perhaps he is moved by the man’s plight and their common humanity. Perhaps he is touched by the desperate situation in which this slave finds himself. Perhaps he sees the crippling intergenerational chains of debt that might bind this slave’s children and grandchildren. Perhaps he is a compassionate person. Though perhaps he may only see an economic opportunity; it may be worth more to see this servant free, to exchange an unpayable financial debt for a more useful personal obligation to the king.

We never learn of the source of the king’s pity. His motives could be pure or muddled. This insight is an excellent reminder that Jesus’ parables are rarely simply allegories, wherein characters can be easily attached to God or us in the drama of salvation. Not all kings are stand-ins for God in the parables; instead, we may find God in the interstices of this stories as much as in their explicit characters.

The now liberated servant leaves with a whole new life available to him. However, in short order, he shifts from servant to lord, debtor to creditor. Encountering one of his fellow slaves, he demands that a relatively smaller debt be fulfilled immediately. Unable to pay, the slave is thrown in jail. Once the king hears of his erstwhile slave’s callous reaction, the king demands that the (former) slave be tortured “until he would pay his entire debt” (verse 34). The implication of this conviction is gruesome though left largely to the imagination.

Jesus concludes by noting the seriousness of our forgiveness of others. Just as the faithful hold the ability to bind and loose, our unwillingness to forgive will redound on us. Forgiveness is neither optional nor contingent. Why? Because God’s forgiveness knows no end and so also should our relationships be governed by a grace that knows no bounds.

Like last week’s invocation to confront a disruptive person in the community, Jesus’ teachings on forgiveness could well be abused. Forgiveness does not mean the embrace of violence perpetrated against us. It does not mean giving free reign to those who would do us harm. It does not mean a ready acquiescence to those who are stronger than us. The context of these teachings is key. Forgiveness is a gift of grace, a reflection of God’s love, not the curse of abuse or a reflection of our worst tendencies as humans.

In this context, the exhortation to unending forgiveness is a counter-balance to the confrontations dictated in the previous verses. Confrontation without forgiveness does not reflect the good news, and neither can forgiveness that eschews the confrontations that made forgiveness necessary in the first place speak truthfully about reconciliation and healing.

September 14, 2014