Many sermons begin with a funny story or captivating movie image told right after the reading of Scripture.

This is the hook — in homiletic technical speech — a way to capture the attention of listeners who have gathered from various quadrants of the community with a multiplicity of concerns ranging from loss of faith to loss of employment.

Our knowledge of the latest breaking news, international and local political unrest, and impending weather seem to provide the best commentary for acknowledging the shared existence of the community of faith.

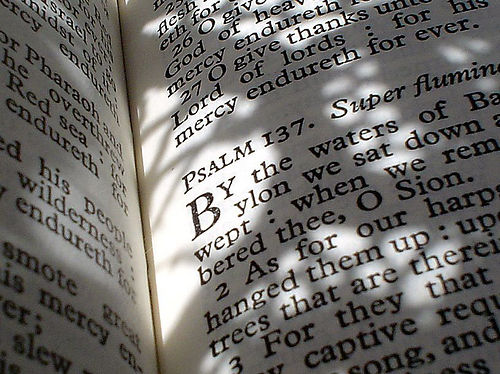

We know that there is a lack of religious literacy even among those who regularly hear sermons. From mainline denominations to independent communities, Christians today lack the capacity to express the biblical revelation of God’s activity in human history as demonstrated in the life of Jesus Christ. The sermon’s task is to counteract the amnesia that has undermined so much of Christian expression.

A few years ago, one of my students prepared a sermon on Psalm 34 as capturing the fear and turmoil of David hiding from Saul in 1 Samuel. The sermon captivated us as we listened because we were invited by description to actually fear for our very lives. After the sermon, the other students asked how the preacher had imagined so clearly the anxiety. The student acknowledged that he described for us his own feelings experienced in a near-death incident in his own life.

What made his message so captivating was that during the sermon, he never injected his life experience directly. While he had used a real-life incident, he didn’t deviate from the biblical narrative by inserting a personal illustration. Instead, he described distress, despair, and disorientation, leaving the story of David central in our imaginations against these feelings of anxiety. This seamless narration proved more memorable than raising our sympathy toward the speaker as he recounted his own story. I marveled at the impact of this telling of the biblical story as it must have been originally passed down through the generations of ancient Israel. Since then, I have encouraged preachers to pause in writing their sermons to craft a biblical narrative rather than merely a biblical idea.

When one thinks of an illustration to insert or an idea to insert, consider if it truly belongs in the scene from Scripture one is rehearsing. If so, can the point be made directly in the biblical episode?

An example is to describe John’s care for Mary, the mother of Jesus, after the crucifixion, as ministry to a middle-aged Palestinian woman who has just attended her son’s public execution. In our current political reality, these words carry the weight of both the death of Jesus and the massacre of young men today in ethnic wars. Who cares for their mothers?

Or maybe one could describe Eve’s parsel-tongue encounter as leading to the first residential foreclosure. While beckoning images of our movie-going imaginations, the context remains a narrative of detrimental consequences resultant of a verbal exchange with a serpent. Suddenly J. K. Rowling is not so original and the biblical narrative is recovered as humanity’s foundational story. One-liners and intentional turns of phrases register the force of the biblical image against the realities our listeners experience today. God’s people then, and now, can trust the comforting intrusion of the Holy Spirit.

What do your listeners do with the sermons you preach?

Are their lives a continuation of the drama of God or do they leave the Sunday service as consumers and commentators imitating and supplementing the world as presented by the networks? Just how do we captivate the imaginations of a high-tech audience with instant global news, and portable movie theaters on handheld devices?

Timeline, Redefined

Here we are, thousands of years later, reading an ancient equivalent to Facebook. Everything from the transcripts of the spoken messages of Jeremiah to the Letter to the Hebrews are ancient blog posts sent out through the progressive technological advancement in communication known then as writing.

As the media continues to exploit negative images of religious practice, people of faith must negotiate the question of how to speak of spiritual disciplines in a secular society. A final example might be how to speak of sharing meals. From Adam and Eve’s sin-filled snack in Genesis and the wilderness-wandering worship community’s servings of fast food to Jesus’ stories of banquets and practice of smoked-fish fellowships, gathering at the table to feast serves as a constant metaphor for community formation. Describing the multiethnic, intergenerational, bilingual fellowships in the Epistles with attention to the gatherings for refreshment rather than merely a weekly ritual, may invite Christian dining with neighbors rather than religious spates over Eucharist.

Such fluency with the language we call Christian requires a grasp of the entire biblical narrative; an imagination informed of God’s purpose and the speech to convey it in a world that can’t conceive the divine intention to restore the goodness of creation. This requires conveying Scripture in order to expose the reality it is narrating.

What we craft as a Christian sermon should expose our listeners to the drama suggested in the storied testimony to God’s justice, in such a way as to make discernible its demonstration in the life of Jesus. Such a message will recover the witness to the God of Jesus Christ as the shared knowledge of the community of faith called Christian.

I believe the most effective proclamation of the word of God … the most effective way to tell this story … is to tell it in such a way that the drama it tells happens all over again — first among the listeners who call themselves followers of Jesus.