Commentary on Psalm 23

Well, here you are, wondering whether to take the leap of faith and make Psalm 23 the text for — or at least an important element of — proclamation for the 8th Sunday after Pentecost.

You may be aware of Walter Brueggemann’s verdict, namely, that commenting on this psalm is “almost pretentious.”1 If Brueggemann feels that way about commenting on it, where does that leave us with preaching it?

But before we sell ourselves short, I want to persuade you that there are ways to share this beloved poem with your congregation so that they discover new insights for themselves. A psalm as treasured as this one deserves a bold homiletical move, something that takes us and our hearers outside the “comfort zone” of a typical sermon. This might mean something more interactive, creating space within the message for meditation, conversation, song, or prayer. It might mean a different homiletical style from your “bread and butter” outlines and stories: perhaps an imaginative, perspectival testimony on the ways you, as their shepherd, have been one of the “sheep of God’s hand” (Psalm 95:7); or a dialogue/round table with two or three members of the congregation (some newer and some longer-term members) who each comment on an element of the psalm. If those ideas make you nervous, then at least craft your points, illustrations, and applications to get at something new for them, perhaps along the lines of, “What you didn’t know about Psalm 23 that will make you love it even more!” Regardless of the homiletical path you choose, I’m persuaded that your preaching and the congregation’s response will be enhanced by discovering amazing aspects of the psalm’s literary, historical, and theological dimensions.

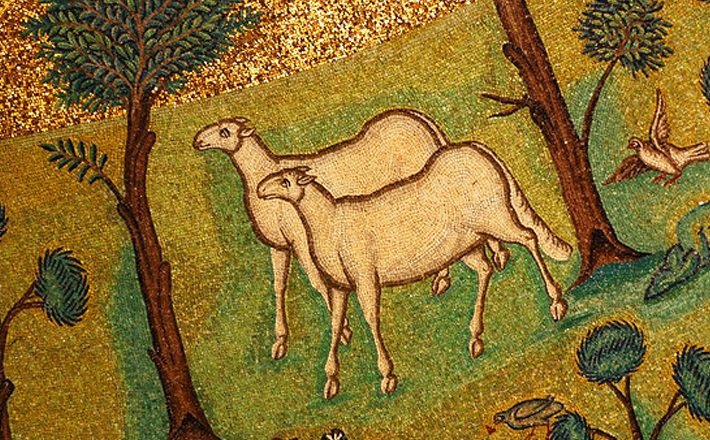

Literary artistry. The basic facts about the psalm preach an eloquent message by themselves. There are fifty-five Hebrew words in this psalm, and unlike many psalms there are almost no repetitions.2 Only the Hebrew words for “Lord” (verses 1, 6), “day” (verse 6, twice), and possibly “restore/return” (verses 3, 6, NRSV “dwell”)3 are repeated. It’s as if the poet were given a list of some fifty words and told to write the most memorable poem in human history. Moreover, a total of fifty-five words creates a precise center (the 28th word), namely, “you,” in reference to the Lord. Thus, the thought at the very center of the poem is the phrase, “you are with me” (verse 4).4 Combine that insight with the closure created by the use of “Lord” in the psalm’s opening and closing phrases, and we see the portrait of the divine shepherd who is there at the beginning, the middle, and the end of our journey. By virtue of its literary artistry alone, therefore, this psalm declares that God enfolds his people so that we all are part of the flock; and yet this shepherd intimately knows the sheep in all their distinction and difference. Each one of us is throughout his or her life a unique and precious possession of God.

Historical context. Scholars have done excellent work explaining the ancient Near Eastern context of the psalm. Still, this is not an idea that every commentary discusses, and it almost certainly is not on your parishioners’ radar. Nevertheless, it is important for grasping the psalm’s meaning in its original context to know that both Egyptian and Mesopotamian cultures used the shepherd image for their kings, their gods, or both. The epilogue to the famous Code of Hammurabi has that king state: “I made the people lie down in safe pastures, I did not allow anyone to frighten them.”5 Or in regard to the image of the banquet (vv 5-6), there is the goddess Anat who “arranges seats for the warriors, arranges tables for the soldiers.”6 The biblical psalmist, being well aware of this broad cultural background, is thus making an affirmation of faith: The Lord — not a foreign god or king — is the only true shepherd of each and every Israelite. We now hear this psalm not merely as a message of comfort on life’s journey but a theological creed spoken in the midst of our own culture with all of its earthly leaders and “gods” that can never be the Shepherd-King of Psalm 23.7

Biblical theology. Finally, while many parishioners will connect this poem with the shepherd images elsewhere in the Bible (e.g., Jeremiah 23, Ezekiel 34, John 10), few will identify the echoes of Israel’s national journey of deliverance, wilderness, and emergence in the land (see especially Psalm 78:52-55).8 This most precious of personal psalms is about both our individual journeys and the journey of the people of God. Finally, biblical theology finds echoes of prophetic themes — the NRSV accurately renders the KJV’s “paths of righteousness” as “right paths” (verse 3) — connecting this psalm to the covenantal standards of justice. And the poet’s sense of protection from the enemies (verse 5) moves toward a richer understanding of reconciliation through the good shepherd who tells us to love and forgive them (Matthew 5:44; Luke 22:34).9

In the end, whatever vehicle you choose to carry the message of Psalm 23, find ways to share insights that increase your flock’s appreciation of their favorite psalm. Far from domesticating it through a thousand and one analytical details, your careful preparation will open up new worlds of meaning for your congregation.

Notes:

1 Walter Brueggemann, The Message of the Psalms (Minneapolis: Augsburg, 1984), 154.

2 I am counting the actual lexical units in Hebrew, not separating out the so-called inseparable prepositions and conjunctions.

3 A. E. Arterbury and W. H. Bellinger, “‘Returning’ to the Hospitality of the Lord: A Reconsideration of Psalm 23,5-6,” Biblica 86 (2008): 387-395.

4 This is a key focus in Rolf Jacobson’s commentary on the passage: “Psalm 23: You are with Me,” in The Book of Psalms, NICOT (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2014), 238-246.

5 See the study by Beth Tanner, “King Yahweh as the Good Shepherd: Taking another look at the Image of God in Psalm 23,” in David and Zion: Biblical Studies in Honor of J.J.M. Roberts, eds. B Batto and K. Roberts (Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns, 2004), 273-274.

6 Ibid, 281.

7 Jacobson calls this a “powerfully subversive element” (245).

8 For a discussion see Richard J. Clifford, Psalms 1-72 (Nashville: Abingdon Press, 2002), 130.

9 See J. Clinton McCann, “The Book of Psalms,” in The New Interpreter’s Bible (Nashville: Abingdon Press, 1996), IV:770.

July 19, 2015