Commentary on Psalm 31:9-16

“Our senses attach all the scorn, all the revulsion, all the hatred that our reason attaches to crime, to affliction … (E)verybody despises the afflicted to some extent, although practically no one is conscious of it.”1

Simone Weil’s description of the social degradation of affliction reflects with devastating precision the experience of the speaker in Psalm 31:9-16. When we see someone who is afflicted, with physical or mental illness, homelessness, disability, we tend, out of fear of our own vulnerability, to recoil, and to regard that person with disdain. When we experience affliction, we see that disdain in the eyes of others, and we even come to believe ourselves to be worthless. Often, acute suffering is, in the eyes of human beings, criminal.

The portion of Psalm 31 appointed for today begins with lament and a plea for God’s graciousness. Prior to verse 9, the psalmist has prayed for God’s deliverance and protection, and proclaimed that God is the one who sees affliction and can provide refuge (verses 1-7). God is praised for not delivering the sufferer “into the hand of the enemy,” but has, in words that recall the covenantal promise of land in Genesis 26:22, set the psalmist’s “feet on a broad place” (verse 8). The opening verses of Psalm 31 acknowledge the psalmist’s suffering, but place emphasis on the speaker’s assurance of God’s deliverance.

But verse 9 begins a powerful lament, one that evokes the psalmist’s physical and psychological torment, and, most poignantly, the devastating effects of others’ scorn. The psalmist pleads for God’s graciousness, “for I am in distress” (verse 9a). The exact nature of this distress is not identified, but its dimensions are clear and familiar to all of us. Pain of some sort has engulfed the sufferer, some affliction that has filled the speaker’s life “with sorrow, and my years with sighing” (verse 10a). Images of physical and psychological pain intermingle, as is so often the case when we experience deep distress. The psalmist’s “eye” and “soul and body” waste away from grief (verse 9b); the speaker’s “strength fails” and “bones waste away” (verse 10b). Acute suffering can consume us utterly; whatever its cause, affliction is felt as deeply in our souls as in our bones.

It is the social degradation, the scorn and rejection of others, which inflicts the deepest wounds upon the afflicted. The psalmist’s tone is one of grief, but also of astonishment, that compassion is nowhere to be found. The speaker is scorned by “adversaries,” which, although troubling, is not particularly surprising. But rejection and revulsion are felt closer and closer to home; the psalmist is “a horror to my neighbors, an object of dread to my acquaintances” (verse 11). Even those on whom one can expect to depend in times of trouble have abandoned the afflicted person. Indeed, the psalmist is as good as dead to others: “I have passed out of mind like one who is dead” (verse 12a). No one gives any thought to one in such great distress. The psalmist feels useless, worthless, utterly unwanted, “like a broken vessel” (verse 12b). The psalmist’s life, indeed the psalmist’s very self, is in shards, and no one has any use for the broken pieces.

This sense of abandonment, however, is accompanied by a terrifying sense that the psalmist is surrounded by those intent on doing harm. The speaker hears “the whispering of many — terror all around!” as others “scheme together against me, as they plot to take my life” (verse 13). Deep in physical and emotional torment, the afflicted one experiences others’ rejection and fear as assault. The psalmist feels both utterly abandoned and utterly besieged, the isolation that affliction engenders feeling like a very threat to the sufferer’s life.

Yet the psalmist continues to proclaim trust in the Lord; indeed, the speaker clings to God as the only one on whom the afflicted one can depend. “But I trust in you, O Lord; I say, ‘You are my God’ ” (verse 14). The isolation and violence that affliction has wrought are contrasted by the “hands-on” imagery of God’s presence with the sufferer. “My times are in your hand; deliver me from the hand of my enemies and persecutors” (verse 15). The psalmist calls on God to let God’s “face shine upon your servant” (verse 16a). This verse recalls the familiar refrain of Numbers 6:25: “the Lord make his face to shine upon you, and be gracious to you.” This is not only a call for God to show God’s favor to the sufferer, it is also a cry for the very presence of God with the sufferer. This verse continues, “save me in your steadfast love” (verse 16b). The word translated as “steadfast love,” hesed, refers to God’s covenantal love for Israel, God’s promise to “be for” God’s people. It is from within that covenantal love that the psalmist calls for God’s salvation, with assurance that it will be received.

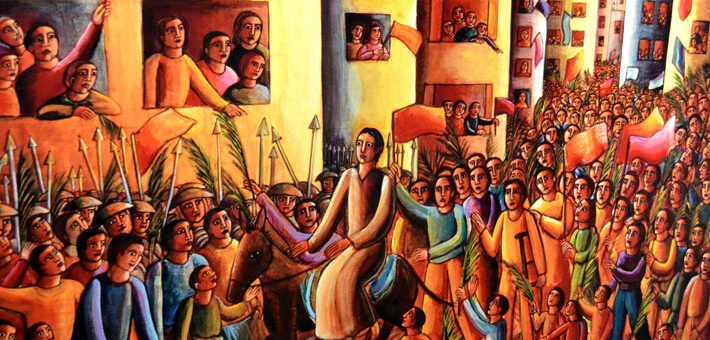

The appropriateness of this text for Passion Sunday is obvious: Jesus is the one afflicted and scorned. Indeed, in the Gospel of Luke (23:46), Jesus utters words from this Psalm on the cross: “Into your hands I commit my spirit” (verse 5). The social degradation and the continued trust in God of Psalm 31 resonate loudly with the Passion of Christ. But how does this text fit with an observance of Palm Sunday? This is the day of Jesus’s triumphal entry into Jerusalem. The crowds that gather do so not to revile him, but to revere him, laying down palm fronds and cloaks to pave his way into the city of God. How does this celebration square with the lament of an afflicted person, rejected and abandoned by others? That human tendency to hate the afflicted, which Simone Weil identifies so aptly, provides a clue. We can turn against each other on a dime. In a matter of days, the crowd that cries “Blessed is the one who comes in the name of the Lord!” (Mark 10:9b) could very well be the same crowd that cries, “Crucify him!” (Mark 15:13). The one who rides into Jerusalem on a carpet of cloaks is also the one who knows our deepest afflictions, and, through the inexhaustible compassion of God, takes them into Godself. We are far from abandoned in our affliction; we are enfolded in the love of God. Being so embraced, we are formed not to scorn, but to embrace afflicted persons whom we meet.

Notes:

1 Simone Weil, “The Love of God and Affliction,” Waiting for God, trans. Emma Craufurd (New York: Perennial Classics, 2001), 71.

March 29, 2015