Commentary on Joshua 5:9-12

The first five chapters of Joshua describe the preparation for Israel’s attack on Jericho in Joshua 6-8.

Chapter 1 reports Yahweh’s commissioning of Joshua, and Joshua 2 tells of Joshua’s sending spies to Jericho and their meeting with Rahab the prostitute. In chapter 3 Israel crosses the Jordan, and in chapter 4 they set up twelve stones, perhaps in the Jordan and on its west bank, in order to stimulate a question by children in the future: “What do these stones mean?” At that time, parents were to tell their children about how Yahweh brought Israel safely across the Jordan.

I have always loved the third verse of the hymn “Guide Me Ever, Great Redeemer”1 it describes our own future passage through death to the life everlasting with an allusion to Joshua 4: “When I tread the verge of Jordan, bid my anxious fears subside; death of death and hell’s destruction, land me save on Canaan’s side. Songs and praises, songs and praises I will raise evermore.”

After two verses describing how all the surrounding nations were struck were terror by Israel’s passage through the Jordan, chapter 5 continues with an unusual account of a circumcision ceremony. Since the first generation that came out of Egypt had died off, and no one had been circumcised who had been born during the forty years in the wilderness, Joshua circumcised all these (600,000?) males at a spot called “Hill of the Foreskins” (Joshua 5:4). Imagine 600,000 foreskins piled high! After a few days of rest and healing (5:8), the Israelites were ready for their next steps, namely, the Old Testament lesson assigned for this day describing the first Passover in the land. According to Pentateuchal law, every male who participated in Passover had to be circumcised (Exodus 12:48).

The safe arrival in the land meant that the disgrace associated with Israel’s slavery in Egypt had been undone. This is stated in a metaphorical way: “I have rolled away” (gallothi) “the disgrace of Egypt” (Joshua 5:9). Therefore the first town they occupied in Palestine was called ever after “Gilgal,” interpreted here as a pun on the words “I have rolled away.” This place, much like the stones in and alongside the Jordan, would be a perpetual reminder of the liberating character of our God. Here is the place where our deliverance from the slavery was so real you could almost taste it.

Passover had first been celebrated on the night of the Exodus itself, with blood on the doorposts and the lintel of their houses, as a sign of their faith and their identity, leading Yahweh to pass over without allowing the Destroyer to enter their houses and strike them down. The repeated observance of this Passover festival would again cause children to ask what this observance was all about and give parents a chance to tell The Story one more time (Exodus 12:23-27). But there had been no intervening celebrations of Passover until Joshua 5. Conveniently enough, the year in Joshua 5 had advanced to the fourteenth day of the first month, the normal time for Passover.

Life returned to normal in one more way. On the first day after this Passover, they ate the produce of the land. The yeast used in Old Testament times was a type of sourdough and since there had not been opportunity to prepare such “natural” yeast; they ate unleavened cakes and parched grain. And then the Manna stopped. Ever since Exodus 16, when Yahweh in response to Israel’s complaint had given them Manna and quails to spare, that Manna had seen them through. Manna had taught them not to hoard their food because Manna that was carried over to the next day bred worms and became foul (16:20).

They had also deposited a jar of Manna in their sanctuary so that future generations would recognize that their ancestors had survived in the wilderness only because of Yahweh’s providential hand (16:32-34). Not that the Israelites had always been happy campers. In Numbers 11:5-6 they had griped about the monotony of their diet. “We remember the fish we used to eat in Egypt for nothing, the cucumbers, the melons, the leeks, the onions, and the garlic.” Did they also remember their slaving on government building projects or their perpetually bad breath?

God’s promises had come true. The Manna was always only a stopgap measure, designed to come to an end after forty years (Exodus 16:35). From now on the Israelites would raise wheat and barley and forget what a miracle daily bread is. Would they forget that first meal in the land? Would they forget their joy at the return to normalcy? Would they long for the good old days of Manna?

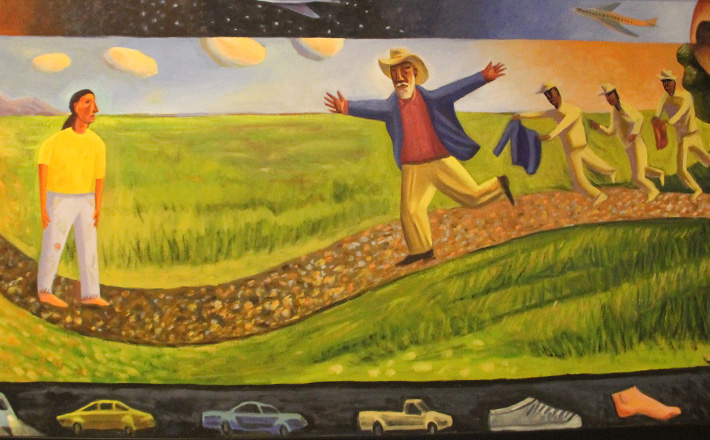

The relevance of this wonderful story for the Fourth Sunday in Lent is not immediately obvious, but there are possibilities. The Gospel for the day is the parable of the Prodigal Son and his elder jealous brother, who was bent out of shape because the father had killed a fatted calf to welcome the prodigal brother home. This link to the Parable might remind us that our daily supply of food is not to be taken for granted and minimalized as if receiving it meant nothing. Of course the father threw a big banquet over his son whom he thought to be dead but who was now alive. But every other day he kept the elder son alive with plenty of food. Every Sunday God offers up a Eucharistic banquet for a bunch of ever-returning sinners, as if it was the first real meal after a barren week. Is not our deliverance at the table so real that we can taste it?

1ELW 618. Once known as “Guide me O Thou Great Jehovah.”

March 10, 2013