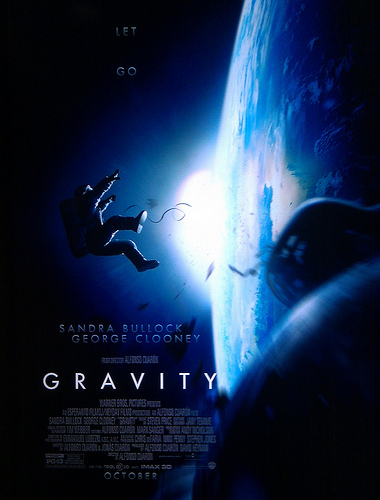

If you haven’t had a chance to see Alfonso Cuarón’s new sci-fi thriller, Gravity, then you need to move it up on your action-item list. The film is as mesmerizing as it is harrowing. In fact, the film is so good that I am wary about sharing this synopsis with the readership of Working Preacher; however, my worries about spoiling the plot are outweighed by my desire to draw your attention to the theological significance of the movie.

So, unless you are up against a tight deadline (Sunday is ever upon us!), I’d suggest that you stop reading now, go watch the movie, and then return to these thoughts after you’ve experienced the film for yourself.

In brief, the film depicts Dr. Ryan Stone (Sandra Bullock), a medical engineer, who is putting her expertise to use to enhance the Hubble Telescope on her first space mission. Stone is accompanied by veteran astronaut Commander Matt Kowalsky (George Clooney), who is enjoying his last trip to space. The work seems routine as Stone tinkers with the telescope and Kowalsky runs laps through space, immensely enjoying his final romp through space. Suddenly, the placid scene turns disastrous when debris from a destroyed Russian satellite collides with the crew’s shuttle, killing everyone but Stone and Kowalsky.

The bulk of the story documents Stone and Kowalsky’s efforts to survive amidst the radically inhospitable environment of space. The pair manages to tether themselves together and make use of Kowalsky’s last bits of fuel on his jetpack to traverse the void in route to a nearby (100 kilometers!) space station.

With her oxygen supply rapidly dwindling, Kowalsky separates himself from Stone to give her a chance at survival. Through creative thinking, coolness under pressure, and a dogged determination to live even when all hope seems lost, Stone manages to navigate a rescue pod back to earth. The film ends with Stone’s awkward first steps on an isolated beach — she is readjusting to gravity and, it seems, to an entirely new approach to living.

The film is rich with symbolic significance, and preachers will enjoy teasing out deeper meanings layered within the plot. Consider, for instance, the significance — the gravity — of prayer and its power to engender hope and perseverance. But even greater than these other theologically and philosophically rich textures within the film, I was struck by the relationship between the lead characters. It helped me see Christian discipleship with fresh eyes.

In Gravity we find a poignant portrayal of what Christian discipleship might look like. As it is in life, many instances of discipleship arise from circumstantial factors. Folks happen to go to the same church or work at the same office…or board the same spaceship.

The first thing we see portrayed in the film in this regard is that of modeling. Kowalsky is a larger-than-life kind of character. His playful banter, old-school country music that he blasts in his spacesuit, and the wild yarns he spins about his exploits on and off the planet are in sharp contrast with Stone’s cold, meticulous, and uneventful existence. She acts and lives in accordance with her surname.

Second, when all hell breaks loose Kowalsky takes the lead. He is firm and directive about the precise steps they need to take if they are going to have a shot at survival. In no way is he vague or wishy-washy about his instructions, and it is this readiness to take lead that calms Stone down enough to take the necessary steps that will end up saving her life. How often are we explicit about what it means to follow God in the way of Jesus Christ?

Third, Kowalsky is firm but he is also encouraging. Like all good mentors he tempers his instruction with words of praise, and he finds ways to instill his indefatigable hope in his disciple, Stone. This encouragement and support from her mentor gives Stone the confidence to stay cool under pressure.

Fourth, and this point is incredibly blatant, discipleship necessitates that the teacher cut loose from the disciple when the time is right. When he realizes that he is only impeding Stone’s progress, he literally severs the ties between them. The pain of this separation is palpable for the viewer, and it mirrors the pain of the mentor/disciple relationship. There is a natural desire to remain forever tethered in this relationship, but without being willing to cut loose, the disciple can never grow into his or her potential.

Lastly, it is important that the mentor linger. Separation need not be total; the mentor can return to offer words of instruction or encouragement as the need arises. In the film this happens in several moments of dramatic intensity, but I see it most clearly when Kowalsky’s empowering presence is not so obvious. It is seen in Stone’s timid smile and floundering first steps on that deserted beach. It tells me that Kowalsky will never really leave Stone; he has changed her life forever.