Commentary on John 20:1-18

John’s “first installation” of the resurrection appearances includes the following journeys to and from the tomb:

- Mary Magdalene goes to the tomb and back to Simon Peter and the Beloved Disciple (1-2);

- Simon Peter and the Beloved Disciple go to the tomb and then back to their homes (3-10);

- Mary, just outside the tomb, meets the risen Christ and is commissioned by him to bear witness to the resurrection, thus leaving the tomb behind (11-18).

A quick look at how the narrator develops these three “journeys to and from the tomb” suggests a dramatic climax with Mary’s commission and testimony in verses 17-18. Mary’s departure and testimony “unseals” the meaning of the empty tomb, which is otherwise unexplained.

Early in the morning, before light, Mary goes to the tomb. She sees that it is open — she sees that the stone is rolled away, but she does not go inside. She sees, she runs, and she reports what she understands from what she has seen: “They have taken the Lord out of the tomb, and we do not know where they have laid him” (verse 2).

Mary does not “recognize” Jesus as Lord, at least not yet. Other powers — a “they” — have taken a body from the tomb. For her, the memory of Jesus’ death, his internment, had solidified into a reality. This report instigates the journey of the two disciples, Simon Peter and the Beloved Disciple, which extends the question of Jesus’ whereabouts but, most importantly, Jesus’ resurrection identity, and the nature of faith itself, namely believing with and without seeing.

The Beloved Disciple runs faster — is this a comment on his particular relationship to Jesus? — than Simon Peter, but when he arrives at the empty tomb, he stops. The narrator states unambiguously that he did not go in. Why? Was he afraid of what he might see? Or what he might not see? Does he remain outside the tomb for similar or different reasons from Mary?

Simon Peter, who had been following the Beloved Disciple, comes from behind and goes inside the tomb. The Beloved Disciple is still standing outside the tomb. Simon Peter sees the linen wrappings “lying there, and the cloth that had been on Jesus’ head, not lying with the linen wrappings but rolled up in a place by itself” (verse 7).

With the evidence in front of them, their eyes see, but only the Beloved Disciple is said to believe: “[he] also went in, and he saw, and believed” (verse 8b).

What is the relationship between what the Beloved Disciple saw and his response? Not much, according to Gail R. O’Day: “… the beloved disciple believed because he already believed.”1

Maybe believing the promise “finished the race”, while Simon Peter’s curiosity led him into the tomb but no further. In any case, the narrator does not say whether Simon Peter responded to what he saw with belief or unbelief. The result of this “sighting” leads both disciples to return to their homes (verse 10).

What do we make of the differing conclusions of the disciples or the absence of a conclusion from Simon Peter? Perhaps it is simply that the writers of the gospel are not primarily interested in apologetics, or in explaining how the resurrection happened, or whether evidence for it was compelling. They are mostly concerned to show the reader that it happened.

If anything, the gospel writers present the reading community with narratives designed to provoke the reader’s response. The resurrection of Jesus might be condensed to a few spare details (as in Mark’s account) or may include extended narratives like John’s or Luke’s. Either way, the texts pose a similar set of questions for the reader: How do we respond to the empty tomb? Have we skipped merrily from Palm Sunday to Easter Sunday, with barely a regret to darken our way? Or could we be instructed by the honesty of Mary who went to the tomb expecting to find a corpse? She is the one who invites the disciples, and perhaps us as well, to the empty tomb.

Simone Weil, the French philosopher and mystic, sounds as if she might be a friend of Mary’s tears:

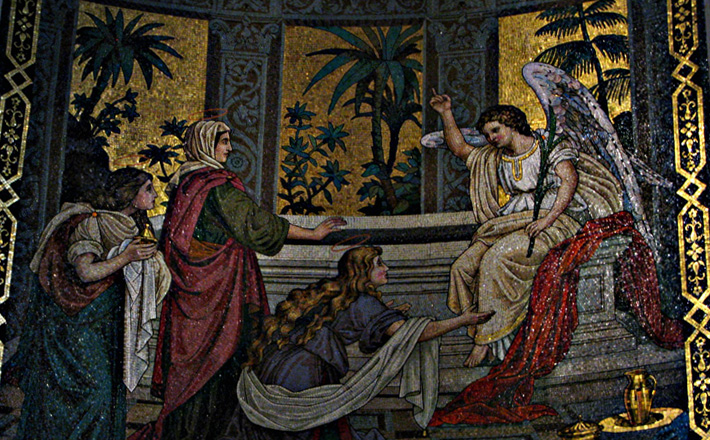

Affliction contains the truth about our condition. They alone will see God who prefer to recognize truth and die, instead of living a long and happy existence in a state of illusion. One must want to go towards reality; then, when one thinks one has found a corpse, one meets an angel who says, ‘He is risen.’2

Perhaps Mary represents one who goes to just this reality. She expects a corpse … nevertheless, she persists.

John’s first installment of the resurrection has not reached its completion. The narrator uses a by now familiar formula for the journey of faith. Consider the call of the first disciples in 1:39-42 or the woman at the well, who “left her water jar at the well and went back to the city. She said to the people, “Come and see a man who told me everything I have ever done! He cannot be the Messiah, can he?’” (John 4:28-29).

The last example foreshadows this text, which reserves the Easter testimony to Mary Magdalene. The Beloved Disciple went home, as did Simon Peter. But Mary remained at the opening of the tomb.

Mary wept. Are we to recall Jesus weeping outside the tomb of Lazarus? It seems all too easy, on our side of the resurrection story (and on Easter Sunday!) to make light of Mary’s bewilderment. Jesus wept, too. Perhaps because of this, Jesus will be revealed to her before anyone else. The disciples, including the Beloved Disciple, went to their homes. Other disciples will be found in another house, one locked with fear. Mary’s eyes were locked in the darkness of grief.

But like the Samaritan woman Jesus meets at the well, Mary Magdalene will eventually leave her grief at the tomb. Where she has known tears, she will be given shouts of joy. Jesus commissions the woman who weeps as the woman who proclaims: “‘I have seen the Lord’” (verse 18b).

Raymond Brown wonders if, when she tried to “hold onto” Jesus, she was trying to return to the way things were before Jesus’ death.3 If she had clung to the Jesus she once knew, could she ever proclaim the Jesus she suddenly recognized as her Lord and God? What are we holding on to in this post-resurrection world? Our grief? Nostalgia for the past?

Jesus appears next in a house filled with fear — but he will not be conformed to fear.

Notes:

1 Gail R. O’Day, “The Gospel of John” in New Interpreter’s Bible, volume 9 (Nashville: Abingdon Press, 1995), 873.

2 Simone Weil, “The Love of God and Affliction” in George A. Panichas, ed., The Simone Weil Reader (New York: David McKay Company, Inc., 1977), 463.

3 Raymond Brown, “John: 23-21” in The Anchor Bible (Garden City: Doubleday & Company, 1970), 1014.

April 16, 2017