Commentary on Isaiah 25:1-9

This chapter juts out of the bleak landscape of judgment and destruction depicted in the previous twelve chapters (Isaiah 13-24). It returns the reader to the theme and object of worship that opened up the section on the nations (Isaiah 12). In chapter 25, the narrative departs from a temporal perspective, with its sequencing of events, and turns toward a heavenly perspective.

Medieval exegetes would have identified chapter 25 with anagogic interpretation because the reader is carried or led (agōgē) above (ana). Eschatology offers a different angle on history. Texts that speak of the end lift us up to look down upon the moments of our lives and see them as part of a more expansive and interconnected landscape.

These verses burst upon the night sky of humanity’s exilic existence by reminding the reader of the God who delivers and what that deliverance will mean. Like all texts that bring to bear a vision of the end upon the present, it marks a call to hope against hope because “the Lord God will wipe away the tears from all faces” (Isaiah 25:8).

God of wonder

The chapter opens with a call to exalt and praise the name of God. While YHWH is the name of God, Isaiah’s favorite elaboration of this name is “Holy One of Israel” (see for example, Isaiah 1:4; 5:19, 24; 10:20; 12:6). To invoke the name is to call to mind the vision of God as the thrice-holy one whose holiness breaks forth in justice and righteousness. For Isaiah, justice and righteousness are a manifestation of God’s holiness, which is refracted through the glory of creation.

God’s name does not point to something abstract. God reveals God’s name in the concreteness of history through acts of deliverance. God is praised “for wonderful things” (Isaiah 25:1). The term translated “wonderful” refers to a wonder. It has in view the miraculous deeds of God. The term stems from the Song of Moses after God has destroyed Pharaoh’s army (Exodus 15). Moses sings out, “Who is like you, majestic in holiness, awesome in splendor, doing wonders?” (Exodus 15:11; see also Psalm 77:15). The holiness and splendor of Yahweh comes through the wonders He performs in the midst of delivering the people of God.

This God of wonder evokes wonder in his people. Like the Psalmist declares after the return from exile, “When the Lord restored the fortunes of Zion, we were like those who dream” (Psalm 126:1). The wonder of things alters our vision, which, in turn, changes our affections and emotions. As we are caught up in the wonder of God, we find ourselves changed.

God of peace

The second part of the passage recounts a kind of reversal of fortune. The mighty are brought low while the poor and downtrodden are raised up. At first glance, this seems like a violent overthrow of the perpetrators of violence as the earthly city is brought into ruin in preparation for the establishment of the city of God (Isaiah 25:2). Yet, even the strong come to glorify God (Isaiah 25:3). The point is that the rage and ruin perpetrated by the earthly city does not mean God will abandon the nations. Instead, God strips the strong. God destroys the false idols that give rise to a false identity.

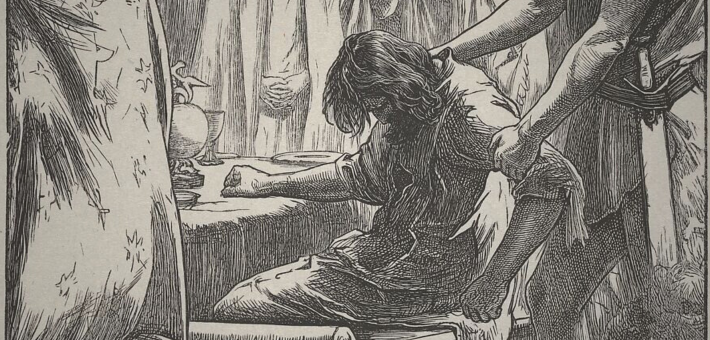

The image of God as a refuge and shade evokes an image of peace. In this passage, the shelter does not remove the violence of the nations but preserves and protects in and through the violence. Israel does not escape the violence, she endures and overcomes in the midst of the violence. To be a refuge and a shade means that God himself is absorbing the violence of the earthly city. These images point back toward the “prince of peace” upon whom the Spirit of the Lord will rest (Isaiah 9:6; 11:1-2) and who will cause the lion to lie down with the lamb. They also point forward to the suffering servant whose chastisement brought about this peace (Isaiah 53:5).

God of all

The first five verses of Isaiah 25 build to a crescendo when YHWH becomes the God of all (Isaiah 25:6). The text makes it plain that God will invite all to the rich feast He prepares on his mountain. The text layers adjectives to evoke a lavish banquet filled with food and drink. One finds an echo of Jesus’ invitation to come and feast with him at the marriage supper of the Lamb (Matthew 22:1-14; Revelation 19:6-8). The Eucharist is but a foretaste of this final feast for the nations. God invites all to come and dine.

The image of eating is not exhausted by the feast. Humanity feasts at the table of the Lord because the Lord has swallowed up death itself (Isaiah 25:8). In the final analysis, it is not Israel or even the nations that are the enemy. It is death that must be defeated. To swallow death is to invoke the idea of God absorbing the blows of death. We return full circle to the idea at the beginning of the passage. Israel’s view of God does not come from abstraction but from God’s concrete actions of deliverance. God becomes the God of all because God enters into death and absorbs it. God is a death eater.

Isaiah 25 compels the reader to view life from a different perspective. Its view from the end lifts up the reader so that the moments of history can be seen in light of a divine plan to wipe away all tears. The faithfulness of God with which the text begins unfolds in the concrete actions of deliverance in which God brings peace by swallowing death and so demonstrating that He is the God of all. As the creator of all things, God will not see his handiwork destroyed. He will redeem the creation by absorbing the violence and bringing to ruin the very mechanisms individuals utilize to perpetrate that violence.

October 15, 2023