Commentary on Hebrews 4:14-16; 5:7-9

Hebrews has the most intricate Christology in the New Testament.

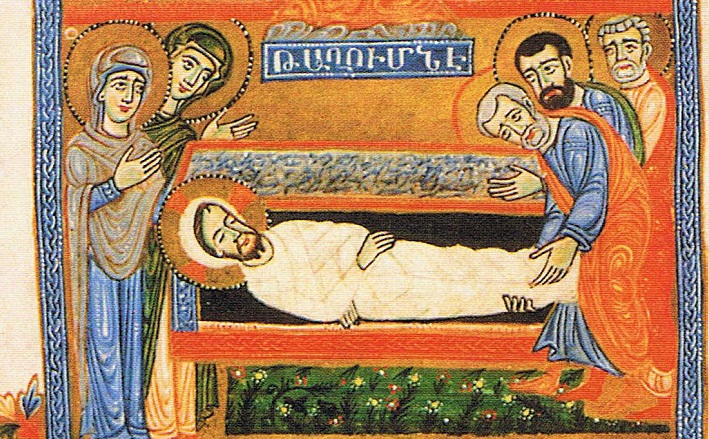

It presents a high Christology in which Christ is the agent of creation and the exalted Son of God and High Priest installed at God’s right hand (especially see the opening of 1:1-4). Yet at the same time, Hebrews stresses how the enfleshed Christ shares every aspect of our humanity with the exception of sin (2:17-18; 4:15). Both emphases also serve as motivational Christology in which the varied presentations of Christ stimulate our perseverance in faithfulness and obedience (12:1-4). All of these Christological elements come together in this Good Friday lectionary text.

Our text opens by presenting dual identities for Jesus as Son of God and High Priest (Hebrews 4:14). His identity as Son of God builds on the Old Testament concept that the Davidic king was regarded as son of God, i.e., God’s regent ruling on earth, especially as presented in Psalm 2 (quoted in Hebrews 1:2, 5; 5:5). In the Old Testament, however, the king and the high priest were completely separate offices as the former was a descendant of Judah and the latter a descendant of Levi. Jesus occupies both positions so that he not only rules the cosmos but also offers sacrificial intercession on our behalf. The image of Jesus passing through the heavens (4:14) builds on these dual identities. As Son, his passing through the heavens involved his fore-mentioned exaltation and installation (1:3-4; 2:9-10). As High Priest, he passes through the heavenly sanctuary and its curtain to perform his priestly duties (6:19-20; 8:1-3; 9:11-12,23-24; 10:19-22). The exhortation at the end of 4:14 (that we hold fast to our confession) is not simply a matter of our belief in Jesus. It also is an exhortation to live out this confession in our persistent, obedient, faithfulness.

Our High Priest’s solidarity with us and sympathy towards us include human weakness and testing which Jesus experienced. For the author of Hebrews, weakness on both our part and Jesus’ part is multifaceted including physical weakness whose end is death (2:9,14-15), social ostracism and abuse (10: 32-34; 12:3-4), and susceptibility to sin (2:17-18; 9:26-28). The only difference between Jesus and us is that Jesus was without sin which enables him to offer sacrifice on behalf of our sins as both the ultimate High Priest and the ultimate sacrifice (2:17; 7:27).

Again, this Christological presentation has a motivational intent. We are now exhorted to approach the divine throne with boldness because it is a throne of grace where we will find mercy, grace, and help throughout our perilous, earthly pilgrimage (Hebrews 4:16). This is a stark reversal of Old Testament sanctuary theology. Only the high priest was able to enter the Holy of Holies to offer sacrifice on the Day of Atonement. Now, however, we are invited to approach the divine throne with boldness to receive all the divine benefits which flow from our High Priest’s sacrifice.

Hebrews 5:7-9 expands on Jesus’ dual identities as Son of God and High Priest. Part of Jesus’ priestly service involved offering up prayers and supplications while identifying fully with humanity (5:7a; note how the technical term “offer up” was also used in 5:1,3 in connection to human priestly service). The exact content of Jesus’ prayers is not directly reported here. Some have sought to connect Jesus’ loud cries and tears in 5:7 with Jesus’ prayer in Gethsemane that the cup of death would be taken from him (Mark 14:36; Matthew 26:39; Luke 22:42). Such a struggle with his fateful death, however, does not fit the theological presentation of Jesus in Hebrews. The thrust here is the emotional depth of his prayers not for his deliverance but for our deliverance as part of his priestly service (2:9; 6:20; 7:25,27; 9:24; 10:12).

A related theological point entails the description of God as “the One who was able to save from death” (Hebrews 5:7). Again, Jesus is not praying that he would avoid death. Rather, he is praying to the One who will save him out of the reality of death through his resurrection and exaltation. Thus Jesus is modeling ultimate trust in and reverent submission to the One who has ultimate power over death as part of his priestly service. He rescues us from death through his own death (2:9,14-15; 9:16).

In Hebrews 5:8 the author is putting his own Christological spin on the link between suffering and learning in Greco-Roman morality. It was commonly understood that moral character was learned and formed through adversity. Here Jesus learns obedience through his experiencing of suffering even though he is God’s Son. His intimate and lofty relationship with God does not render him immune from either suffering or obedience. Instead, his mission as High Priest involves obedience to God’s designs by suffering onto death (Hebrews 13:12). Because this remains motivational Christology, Jesus stands as our paradigm so that we too learn obedience through our experiences of suffering even though we share relational intimacy as God’s children (2:10; 12:6-8).

The result of Jesus’ educational experiences is expressed in Hebrews 5:9 which is unfortunately obscured by English translations which present Jesus as “made perfect” (NRSV, NIV, RSV, KJB). The focus here (and throughout Hebrews) is not moral perfect but soteriological completeness. “Jesus is made complete by his death and exaltation to heavenly glory, so that he now serves as high priest forever at God’s right hand. Others are made complete when they go where Jesus has gone, following their forerunner into the presence of God.”1 Thus Jesus is both the source and the goal of eternal salvation.

Within the context of Good Friday, the centrality of Jesus’ solidarity with humanity and his sacrificial suffering on behalf of humanity stand as central components of this text. In going to his death, Jesus does not renounce his identity as God’s Son and High Priest. Rather, he demonstrates and enacts his identity so that we would experience the salvation he accomplishes for us. As our paradigm, we too embrace the way of the cross to enact our faith, obedience, and perseverance in the midst of weakness and suffering.

Notes:

1 Craig Koester, Hebrews, The Anchor Bible, Vol. 36 (New York: Doubleday, 2001), p. 123.

March 25, 2016