Commentary on Genesis 9:8-17

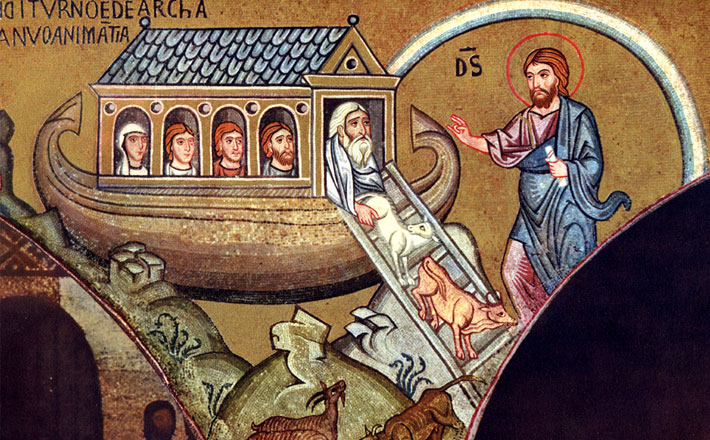

The Old Testament readings for the first three Sundays in Lent give us glimpses of three covenants: God’s covenant with Noah, God’s covenant with Abraham, and God’s covenant with Israel at Sinai.

While each covenant is distinct from the others, taken together they testify to God’s ongoing desire to be in relationship with humanity.

In the ancient Near East, covenants were legal documents, cementing a relationship of mutual obligation, usually between a greater power and a lesser power. For example, a conquering kingdom might covenant not to destroy a losing kingdom, as long as the losers promised to fight against the conqueror’s enemies and to support the conqueror with troops and supplies.1 The obligations are indeed reciprocal, but the power dynamics are not often equal. The Sinai covenant looks remarkably like one of these ancient legal treaties, and the Decalogue, which is read on the third Sunday in Lent, functions as some of the stipulations of that covenant. The Noachic and Abrahamic covenants, though, seem to be of a somewhat different stripe.2

The first thing to notice about God’s covenant with Noah is that it is not, in fact, with Noah alone, nor with only his family, but rather with “every living creature” (Genesis 9:10), “all flesh” (v. 16). God commits God’s self not just to humanity, but to all of creation. The second extraordinary detail about this covenant is that it does not involve the legal reciprocities of a treaty. Instead, all of the obligations rest with God. As Terence Fretheim points out, because this covenant comes without condition, we might think of it as a “promise” rather than a treaty. God reaches out to the world, and God does all the heavy lifting.

For additional exegetical detail I commend to you the two excellent commentaries archived on this site for this text. I also recommend as a resource www.floodofnoah.com, which was created as a space for biblical scholars to engage Darren Aronofsky’s 2014 film Noah. Here I will lift up a few possible directions for preaching this passage:

- God as a God who is moved: God is portrayed in this story, as well as through much of the Old Testament, with characteristics that chafe against all the “omni-” categories we traditionally assign to God: omniscient, omnipotent, omnipresent, or, in the words of the hymn, “Immortal, invisible, God only wise, in light inaccessible, hid from our eyes … ” These categories highlight the influence of Greek tradition on Christianity, which often characterizes God as Aristotle’s “Unmoved Mover.” Yet, in the flood story, God regrets (Genesis 6:6), God grieves (6:6), God remembers (8:1), and God sets God’s bow in the clouds so that God will remember (9:15). In the words of Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel, God is the “Most Moved Mover.”3 It can be disconcerting to think of God’s needing a reminder of God’s promises, as if the rainbow were a string tied around God’s finger, or an alert from God’s Google calendar. Even so, during the season of Lent, the flood story reminds us that God has an “incarnational” side in the Old Testament, too; that is, God has always desired relationship with, and has been moved by the suffering of, humanity.

- Covenant in our daily lives: In its most general meanings covenant is simply a sacred agreement. Particularly in church contexts, the word “covenant” can be used for almost any kind of relationship, from covenants governing behavior at church camps to celebrations of the covenant of marriage. But it is worthwhile to pause and consider the nuances of some of this language. The parallels between biblical covenants and ancient Near Eastern treaty forms emphasize the imbalance of power between the two signatories. Certainly this imbalance holds true whenever God is one of the parties of a biblical covenant, even if the other legal characteristics of covenant are absent (as in the covenants with Noah and Abraham). One hopes marriage, though, is not an unequal power relationship. The legal resonances of covenant also invite images of a quid pro quo connection; one’s own obligations are always dependent on the other’s fidelity to her or his obligations. Yet, in the Noachic covenant, promises are made freely by God and do not count on any reciprocity from creation. The promises made by a church community at a baptism, especially of an infant, are reminiscent of this unconditional covenant. The preacher might challenge the congregation: When do we make promises that we say are unconditional, and yet we end up expecting that we should receive equal “payment” for keeping up our end of the bargain?

- Care for creation: The ecological implications of the flood story are significant. We receive God’s promise that God will never again destroy the earth by flood, yet human sin seems bent on the ruin of creation. As climate change warms the earth and melts the ice caps, the prospect of a flooded earth looms larger every day. Genesis 9 reminds us that God is in relationship not just with humanity, but with “all flesh”; our living on the earth is bound up with the flourishing of all creation, and especially non-human animals. As the Lenten season calls us to repentance, a sermon on the flood could provide a call to repentance from our corporate sins of environmental degradation, as well as a call to action for ecological justice.

Notes:

1 See, for example, “Treaty between Mursilis and Duppi-Teshub,” in Readings from the Ancient Near East: Primary Sources for Old Testament Study (ed. B. Arnold and B. Beyer; Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2002), 98-100.

2 For more on biblical covenants, see Marvin A. Sweeney, “Covenant in the Hebrew Bible,” n.p. [cited 4 Feb 2015]. Online: http://www.bibleodyssey.org/passages/related-articles/covenant-in-the-hebrew-bible

3 Abraham Joshua Heschel, The Prophets (New York: Harper & Row, 1962).

February 22, 2015