Commentary on Ezekiel 37:1-14

Ezekiel 37 is probably the most well-known passage from this prophetic book. Inevitably, when I tell people of faith that I am writing about Ezekiel, they mention the valley of dry bones. So, the imagery may be familiar to many congregants—perhaps because of songs like “Dem bones, dem bones, dem dry bones”—but the historical context for this vision may be lacking.

Prioritize situating this vision within its historical context before moving to our Lenten context.

My personal connection to this passage goes back to college, when, as a naïve but earnest ministerial student, I preached my first sermon ever in a rural Alabama church on Ezekiel 37. I don’t have a copy of that sermon, and I don’t remember many details. But I remember doing my exegetical homework on the biblical passage at my college’s library and preaching about exile and national restoration. I didn’t connect the passage to individual resurrection or to Jesus, leading to an evaluative remark from one congregant afterward. He said, “I’ve never heard that story preached that way before.” I wasn’t sure if it was a compliment! But I did learn at an early age that these churchgoers were reading the Bible differently than my commentary writers.

It may be that people in the pews also think in terms of individual resurrection when hearing this passage; it is a prevalent reading based, of course, on the Christian and Jewish traditions, which have frequently understood the issue present to be one of literal resurrection. So the preacher needs to lean into a communal understanding. Verse 11 in this passage clarifies that the bones are “the whole house of Israel.” Consider whether resurrection—in the sense of individuals rising from the dead—is the appropriate word for a Lenten sermon and this passage.

During the season of Lent, we will profit by grounding this prophetic visionary experience in Israel’s exilic moment. God’s people have lost their most cherished theological realities: the land, the temple, and the monarchy. They find themselves amid a theological crisis. The anchors for their relationship with God have been upended. Their traditional theologies—based on God’s covenants with Moses and David—are failing. Zion is no longer the home for God and God’s people. This new experience of exile calls forth a new reconceptualization of God and God’s dealings with the people.

How could God allow such a disaster to occur? Where is God during this devastation and loss?

The first half of the book of Ezekiel contains one answer to these questions. The prophetic oracles and visions and sign-acts explain that the people are rebellious and at fault. Their disobedience has led to this unfortunate moment.

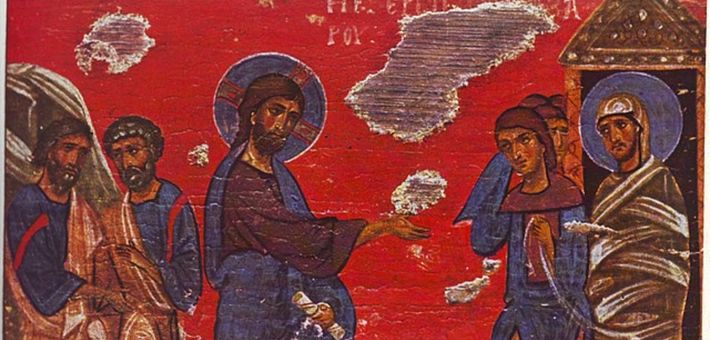

Yet, in the book’s second half, the prophet turns to consolation and oracles of promise. Ezekiel’s vision of a valley of dry bones is one of these places of promise within the book. The prophet is brought to a valley, a low place filled with bones. In this vision, these dry bones represent the people in exile (verse 11). They feel like dry, hopeless, weary people in a foreign land. But God does not leave them as dry bones!

God breathes into these bones, covers them with skin, and places flesh on them. God revives them, and they become alive again.

The vision serves as a promise to God’s people that they will be restored. God will take the dry bones and create a new future—a future with God’s spirit within, a future in the land of Israel (verse 14).

At this point, the preacher can pivot to our contemporary Lenten season. The themes of loss and renewal are fruitful areas to explore. We have all experienced life as a valley, a hopeless and destitute reality. Hardship and trouble are not unknown concepts to God’s faithful people. Our Lenten emphases concerning repentance, sin, and the cross may be mentioned to create a fuller picture.

The faithful life is not without its serious challenges.

For those of us with privilege, we do not want to overestimate our sorrow either. As a White Christian American, I am not persecuted by my government or society. We must be careful that we don’t always see ourselves in the role of exile, especially when we may need to look at ourselves as the oppressor who contributes to others’ exile.

The prophetic vision intervenes in this depressing situation with good news: God brings life from death. God restores the broken!

God does not leave us where we are.

God is present with us in the struggle. The Psalmist reminds us: “Even though I walk through the darkest valley, I fear no evil, for you are with me” (Psalm 23:4).

Ezekiel’s vivid vision of transformation provides hope in the middle of a complex and painful calamity. Dry bones are not the last word.

March 26, 2023