Commentary on Psalm 47

Psalm 47 is a hymn celebrating Yahweh’s dominion over the entire world.

It was probably a part of a yearly ritual of divine enthronement in which the community affirmed the kingship of Yahweh.

Historical and ritual background

Psalm 47 is one of several so-called enthronement psalms (Psalms 93, 94-99). Establishing the details of the ritual lying behind these psalms has been a source of intense debate and speculation. While we cannot be certain, the activities may have included a procession of the Ark of the Covenant up the temple mount and into the temple.

The ascent would have represented the re-affirmation of God’s powerful presence in the midst of the community. Such rituals provide encouragement to people struggling to understand their place within complex and rapidly changing geo-political events.

Literary structure

Psalm 47 is anchored by three statements in the imperative mood (vv. 1, 6, 7). The first of these is a command to “all you peoples” (v. 1). The “peoples” in this context include the foreign nations surrounding Israel, who in all likelihood would not have been present at such a festival. With this audacious summons to all people, present and absent, the psalm reveals the vast scope of Yahweh’s dominion at the very outset.

Most calls to praise in the Psalter are followed by a “motivation clause,” a statement describing why one should praise. In this case, the motivation in v. 2 is God’s awesome power and kingship over everything and everyone. The logic is simple. Since God is king of the earth, the entire earth should praise God.

The initial imperative statement in v. 1 is echoed in v. 6, with the quadruple imperative “sing praises” (Hebrew: zameru). It is remarkable to find the same Hebrew verb repeated four times in a single verse. One rarely sees such redundancy, so the message of this verse is utterly unmistakable. The psalm is calling the people to make some noise! These praises add volume to the sounds of clapping (v. 1), shouting (vv. 1, 5), and blasting of a trumpet (v. 5). And once again, the motivation for these peals of praise is God’s worldwide kingship (v. 7).

Verse 7 ends with yet another imperative: “sing praises (Heb: zameru) with a psalm.” The “psalm” is probably this very psalm. So Psalm 47 uniquely refers to itself as the proper musical accompaniment for God’s ascent.

The Logic of Exaltation

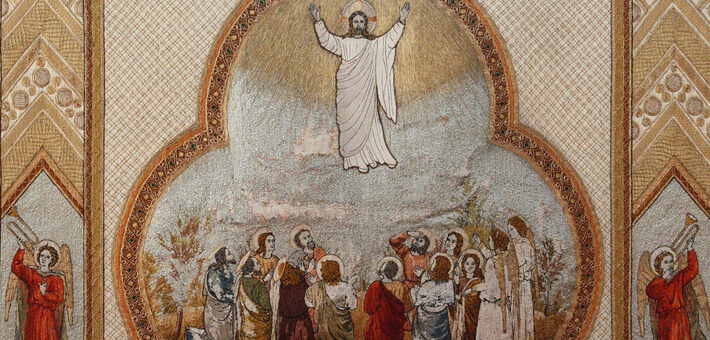

The hymn relies on the logic of exaltation whereby the highest things are the most important and powerful, while the lowest things have the least power. This sort of hierarchy was pervasive in the ancient Near East and was even reflected in the art of that period. Important people (especially kings) and gods often occupied the highest place within any given artistic scene. This artistic convention often meant that the god or king was pictured much larger than the other figures in the scene. As such, the figures of gods and kings were simultaneously “awesome” and “most high,” much like Yahweh is described in this psalm (v. 2). For pictorial examples of this logic of exaltation, see the images of the sun god Shamash on the famous Tablet of Shamash in the British Museum and Rameses II receiving suppliants from the Temple at Abu Simbel.

Consistent with these ancient modes of representation, in Psalm 47 Yahweh’s position shows Yahweh’s dominance and superiority. The psalmist uses the divine epithet, ‘elyon in v. 2, a word derived from the verbal root ‘alah, meaning “to go up.” The -on ending is a superlative, suggesting that Yahweh is the one who has gone up the highest. So ‘elyon is rightly translated, “Most High” (v. 2).

The psalmist uses the preposition ‘al “above/over,” which is also related to ‘alah, to describe Yahweh’s relative position to “the earth” (v. 2) and “the nations” (v. 8). Yahweh is above everything and everyone. Again and again, Yahweh’s dominance manifests itself in explicitly positional terms. The psalm, in fact, ends with this idea by way of climax: “God is highly exalted.” And here again the psalmist is using a form of the verb ‘alah, “to go up.”

Yahweh’s exaltation and Jesus’s ascension

Psalm 47 presents a picture of Yahweh as the exalted king who is most worthy of praise. His high position and supreme authority outstrip all others, especially any earthly leader who might contest God’s power. Any challenges to God’s power are in vain. The psalm ends with a description of the princes of the earth gathering around God’s holy throne in an expression of fealty and submission (v. 8-9).

Many ancient texts refer to the king as the “shield” of his people (see e.g., Psalm 84:9). That “the shields of the earth belong to God” thus suggests that either that Yahweh has conquered all the kingdoms of the earth or that kings of the earth reign at Yahweh’s pleasure alone, that they are Yahweh’s instruments. Both ideas are attested elsewhere in the Old Testament. In either case, Yahweh’s supreme position is without question.

On the Sunday of the Ascension of the Lord, the lectionary readings focus on what it means for Jesus to ascend into heaven (Luke 24:51) and be exalted and enthroned at the right hand of God the Father. There, Jesus is “far above all rule and authority and power and dominion, and above every name that is named, not only in this age but also in the age to come” (Ephesians 1:21). Moreover, following the logic of exaltation, God “has put all things under his feet and has made him the head over all things for the church” (Ephesians 1:22, NRSV).

Jesus’s ascension to the highest heaven is essentially an affirmation of his authority over everything. As the ancient community celebrated Yahweh’s kingship and authority over all earthy powers, so the Christian community celebrates Jesus’s authority.

Jesus’s ascent is all the more powerful because it follows on the heels of a remarkable descent. Jesus descended to earth in human form and died the lowly death of a criminal at the hand of the state. And, as the Apostolic creed affirms, he went all the way down, descending into hell itself.

After this descent, the ascension of our Lord confirms God’s ultimate power over the greatest powers of the earth: suffering, sin, and death. Because God is the king over all the earth, we must respond to the psalmist’s unrelenting command: “sing praises to God, sing praises; sing praises to our King, sing praises … Sing praises with a psalm!” (Psalm 47:6-7).

May 14, 2015