Commentary on Genesis 27:1-4, 15-23; 28:10-17

Is there a theological benefit for a community to traffic in trickster tales?

Biblical authors intended their audience to identify with the people of Israel, and here, in Genesis, Israel is one person. That person starts out with the name Jacob (Genesis 32:28), and Jacob is the quintessential trickster. Why would they want to remember themselves—or why might we want to think of ourselves—as (spiritual) descendants of the trickster?

There are several possibilities. Here are three.

1. Humor can challenge us without making the audience too defensive.

If a reader is willing to entertain a humorous reading, our lectionary reading starts with a funny story. Isaac plans to bless his eldest son, Esau. At first, it might sound touching that Isaac wants to share one “last supper” of his favorite food with his son before a blessing and death (Genesis 27:1–4). But one might also see this as silly. Isaac is at least 20 years from death (31:38; 35:29); he is not going to die any day now, as he conjectures (27:2). Moreover, we have learned that Isaac’s favor for Esau over his twin, Jacob, is because he is a fan of the meat Esau hunts (25:28). Is Isaac being dramatic because he craves some tasty venison?

The ancient Israelites practiced primogeniture, the bestowing of certain privileges on the eldest son, like a double portion of the inheritance and a special blessing. Thus (other than the fact that firstborn arguments sound ridiculous coming from twins), Isaac does not need an excuse for the favor he feels toward Esau. However, Genesis is a book where primogeniture is constantly unsettled; almost every family has a younger son gain God’s or their father’s favor over the eldest son. In this case, it is comical.

With incredible ploys, Rebekah helps her favorite son, Jacob, trick Isaac into thinking Jacob is Esau. Knowing that Isaac will be relying on other senses than his failing vision (27:1), she prepares a tasty meal from a young goat to replace the game Isaac is expecting Esau to bring. While the tastes might be similar, it is hard to believe that Isaac cannot recognize the difference between his favorite meals. Even more unbelievable is Rebekah’s plan for Jacob to use goat hair to imitate Esau’s hairiness (27:9–16). But it works! Even though Isaac voices suspicions that “Esau” has returned too quickly, and “Esau” is speaking with Jacob’s voice, the goat hair convinces him that “the hands are the hands of Esau,” and that is enough to trump Isaac’s doubts (27:20–23).

Presenting this as an amusing account can impact the mood of listeners. Because of the humor, an audience dwelling on this text might be more receptive than defensive when the preacher/teacher transitions to questioning our society’s established norms or challenging listeners based on their similarities to Rebekah, Jacob, Isaac, or Esau.

2. The deception of Rebekah and Jacob undercuts simplistic presumptions about humans, God, and blessings.

The lighthearted reading above is more acceptable when we (following the lectionary) do not think about the family’s reactions: Isaac’s violent trembling, Esau’s bitter cry and weeping, Esau’s homicidal desire, and Rebekah’s fear (Genesis 27:33–45). Although trickster stories can be humorous or fun, a compassionate approach with questions about morality can complicate ideas about God’s blessings.

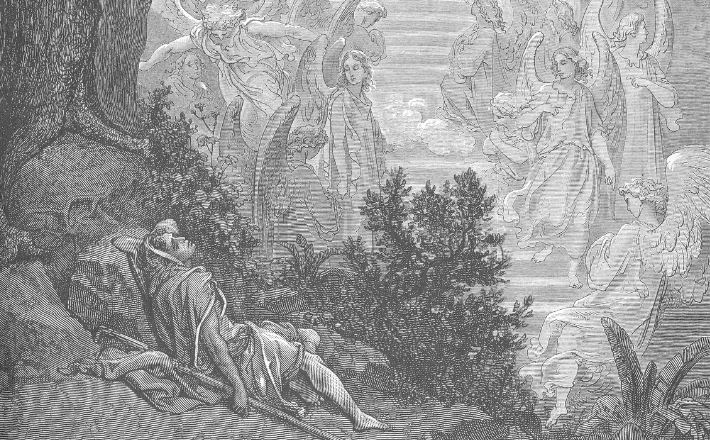

For example, one cannot maintain a facile binary of God aligning with good behavior against bad behavior when we see that Jacob, the deceiver (27:15–23) is the same one who later experiences a dream-vision of God’s magnificent promises passed on to him (28:10–17). This is a story of election, God favoring a person or a people over others, and (as other commentators have highlighted) it is a theological issue Christians and Jews must wrestle with in compassionate and responsible ways.

Election of Jacob starts in utero, but not in the way interpreters—or even Bible translations—usually think. When Rebekah is pregnant with twins, she inquires of God and receives an oracle: “Two nations are in your womb, and two peoples born of you shall be divided; the elder shall serve the younger” (25:23).

Jacob is the younger twin. Therefore, readers usually think of Rebekah and Jacob as fulfilling God’s will through trickery. But the Hebrew of the oracle is surprisingly ambiguous about who serves whom. It could be translated “the elder shall serve the younger” (New Revised Standard Version Updated Edition) or the opposite, “the elder, the younger shall serve.”1

This means that our lectionary is a story of Rebekah initiating a deception while taking a huge risk—“Let your curse be on me, my son” (27:13)—because she is following her own interpretation of God’s will. When she acts boldly, she is not following God’s unambiguous will; it is her interpretation of God’s word.

Do we ever really know God’s will? If we have the humility to respond, “Not for certain,” are we willing to take ownership of the role that we, as interpreters, play in making meaning of God’s word—in applying God’s word through action? Can we imagine good things in our lives—what we see as blessings from God—as simultaneously problematic? This trickster story in our Scripture prompts these types of questions.

3. Identifying with the trickster is a strategy for survival.

During World War II, Zora Neale Hurston wrote an article advocating the value of the trickster found in folklore passed down from African American enslaved people. She referred to him as High John de Conquer but added that he came in songs and stories in several forms, including as Old John or Brer Rabbit. In thorny situations, he usually won the day by making a way out of no way. But even when he did not, it was important that he brought laughter and hope.

Hurston writes that he “was really winning in a permanent way, for he was winning with the soul of the black man whole and free. So he could use it afterwards. For what shall it profit a man if he gain the whole world and lose his soul? You would have nothing but a cruel, vengeful, grasping monster come to power.”2

In other words, Hurston writes that a people without the power to prevent their suffering crafted stories and songs that, through laughter and hope, helped them hold onto their humanity.

In times like these, I think about the value of Jacob’s stories for communities who are suffering. I wonder if a good laugh and a glimmer of hope from stories of Jacob’s trickery, combined with God’s solidarity, can—like Hurston says about John de Conquer—help us survive in such a way that we will not lose our soul.

Notes

- Richard Elliot Friedman and Shawna Dolansky, The Bible Now (New York: Oxford University Press, 2011), 86–87.

- Zora Neale Hurston, You Don’t Know Us Negroes and Other Essays, ed. Henry Louis Gates Jr. and Genevieve West (London: HQ, 2022), 30. Originally published as “High John de Conquer.” The American Mercury, October 1943, 450–58.

PRAYER OF THE DAY

Loving God,

Like Jacob, who dreamed of your promises, you have filled us with dreams, too. Show us your promises in our dreams, and give us ability to follow our dreams. Amen.

HYMNS

Blessing and Honor ELW 854

Spirit of God, descend upon my heart ELW 800, UMH 500, NCH 290

CHORAL

Spirit of God, Robert Chilcott

September 21, 2025