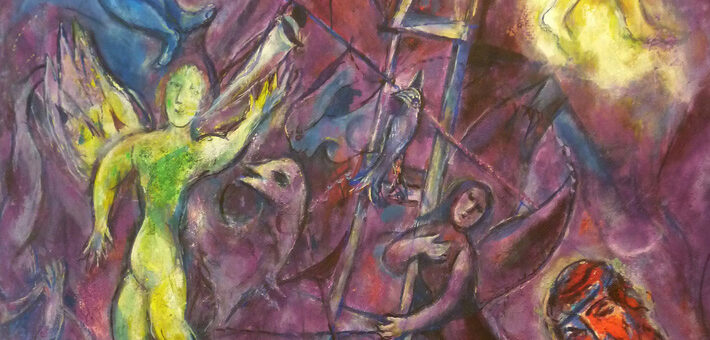

Commentary on Genesis 27:1-4, 15-23; 28:10-17

Does God pick favorites?

Most of us would like to say, “no.” Such an idea would seem to go against foundational democratic values like equality and fairness and we have come to associate these principles with right and wrong. Yet the Bible is full of examples where God seems to pick a favorite: Abel (not Cain), Sarah (not Hagar), Israel (instead of all the nations of the world).

Some Christian readers might like to think that this is an “Old Testament” or a “Jewish” problem, but such a claim is not only prejudicial; it is also grossly inaccurate. In Jesus’ parable of the prodigal son, for example, the younger sibling is given favorable treatment compared to the older. The apostle Paul explained that Israel remained God’s chosen people and that the gentile Christians were being grafted in (Romans 9-11). The author of 1 Peter goes even further, taking Old Testament monikers reserved for Israel and applying them instead to the church, “a chosen race, a royal priesthood, a holy nation, God’s own people” (1 Peter 2:9; see also Exodus 19:6).

The idea that God chooses some and not others (which theologians sometimes call “election”) is inescapable in scripture and elemental in both Jewish and Christian theology. Opinions about election vary and have been contested throughout history. There is no systematic presentation of election in the Bible. Even so, and regardless of whether we like it or accept it, election is an idea that working preachers must wrestle with and perhaps thereby find ways to engage it faithfully and compassionately.1

One place in scripture where we can do this is in God’s curious decision to choose Jacob. As other workingpreacher.org authors have recognized, Jacob is presented in Genesis as disreputable and manipulative. Indeed, very often in the Bible, God’s chosen ones do nothing to deserve this status. They are simply “loved” (Deuteronomy 7:7-8) or “favored” (Luke 1:28-30) for reasons that are never explained.

Such a policy can feel arbitrary, but if we are honest, it is also reflective of the world that we live in. The existence of a favored child is a painful reality in many families. Moreover, “privilege” can function as a kind of chosenness when it relates to matters of gender, race, class, and sexual identity. Many modern societies are slowly waking up to the fact that various benefits once thought of as deserved have in fact been the products of unearned privilege all along. In light of these realities, election in the Bible may be read not as a prescription for the way things ought to be, but as a description for the way things so often are. Schemers like Jacob really do get ahead sometimes.

Despite this, it is not so bad for Esau. Contrary to popular expectation, God rarely curses those that are not chosen.2 For example, God blesses Esau with wealth, children, and a long life (Genesis 36:1-14; see also Ishmael’s blessings in Genesis 25:12-18). This happens even though it is through Esau’s younger brother, Jacob, that God’s promise to Abraham continues.

More broadly, God’s command to Israel regarding the “non-elect” that live among them is unequivocal:

When an alien resides with you in your land, you shall not oppress the alien. The alien who resides with you shall be to you as the citizen among you; you shall love the alien as yourself, for you were aliens in the land of Egypt: I am the Lord your God (Leviticus 33:33-34).

Thus, to be non-elect is not the same as to be hated or despised. To the contrary, the non-elect often benefit from the specially ordained tasks that God gives to the elect. For instance, this seems to be part of the rationale behind God’s selection of Abraham (Genesis 12:2-3). This theological truth has weighty implications for mission and evangelism.

As anyone who has been the “golden child” of their family might attest, sometimes it is better not to be chosen in the first place. There are higher expectations (Deuteronomy 4:5–8) and more severe punishments (Isaiah 40:2). Often, there is pressure to be an example to others (Deuteronomy 4:58). One does not always ask to be chosen but, once established, it is not a relationship that can be rejected (Leviticus 20:26).

More tragically, the most consistent trait across all of the chosen ones in the Bible is suffering. Abel dies while Cain lives. Hannah is ridiculed for her barrenness and suffers bitterly for it (1 Samuel 1:15). As the prophet tells it, the suffering servant was chosen in order that God might “lay upon them the iniquity of us all” (Isaiah 53:6). Most spectacularly, Jesus, the “beloved son” in whom God is “well-pleased” (Mark 1:11) is crucified. According to John’s Gospel, to be chosen by Jesus is to be hated by the world (John 15:19). Such an idea is contrary to much popular Christian teaching but that is the cost of discipleship.

There are so many unanswered questions regarding God’s choice of Jacob. Did Jacob know what he was getting into when he stole his brother’s birthright and blessing? Did God choose Jacob because of or in spite of these deceits—or were they irrelevant? What is clear is that God’s promises to this trickster are exceedingly generous and unconditional (Genesis 28:13-15). No one could deserve such a gift, especially Jacob.

As children of God and followers of Jesus, we have been chosen as well, and not because we earned it. Not all of us are chosen for the same roles or at the same times. The body of Christ is blessed with a variety of gifts, after all, and no one of us has all of them (1 Corinthians 12:4). Yet whatever is our status, we can trust that God’s promises endure, whether it is our turn to be the blessed or the blessing.

Notes

- An exceptional book on this topic is Joel S. Kaminsky, Yet I Loved Jacob: Reclaiming the Biblical Concept of Election (Nashville: Abingdon, 2007).

- There are certain groups, whom Kaminsky calls the “anti-elect,” that are cursed, however. These include the Canaanites, the Amalekites and (in some texts) the Midianites. The history of the interpretation of these peoples in the Bible by Jews and Christians is complicated and often tragic, but we should also recognize that they are the exception and not the rule for God’s policies towards the “non-elect.” See Kaminsky, Yet I Loved Jacob, 111–19.

PRAYER OF THE DAY

Loving God,

Like Jacob, who dreamed of your promises, you have filled us with dreams, too. Show us your promises in our dreams, and give us ability to follow our dreams. Amen.

HYMNS

Blessing and Honor ELW 854

Spirit of God, descend upon my heart ELW 800, UMH 500, NCH 290

CHORAL

Spirit of God, Robert Chilcott

September 26, 2021