Commentary on Exodus 32:1-14

The broader context of Exodus:

The famous, indeed infamous, episode of the Israelites’ most profound moment of disobedience must be understood in the context of the book of Exodus as a whole. As Dennis Olson has observed, Exodus moves from liberation of God’s people out of bondage, to the formation of the people in the wilderness and at Sinai, to the restoration of the people following the dramatic disobedience in the golden calf episode.[1]

Further, Ellen Davis has observed that the book of Exodus is bookended with building projects that are diametrically opposed to one another: at the beginning the people build structures for Pharaoh, to whom they are in a posture of servitude, and at the end of the book the people have built a structure—the tabernacle—for God, who has liberated them for joyful service (as in English, the Hebrew root is the same for both words).[2] The contrast is absolute because in Exodus God seeks the flourishing of the people in two ways:

1) through the covenant that binds them in life-giving relationship to God, and to which the people assent at Sinai; and

2) God seeks to dwell among the liberated people as they journey. That is the point of building the tabernacle: with God present among them, the community will flourish.

The people’s disobedience

In the midst of this story from liberation to formation to restoration comes the people’s dramatic disobedience. Note that from a narrative point of view, the people’s disobedience (32:1) follows immediately upon their assent to be God’s covenant partner (24:3, 7), insofar as chapters 25–31 are a separate block of instructions for building the tabernacle.

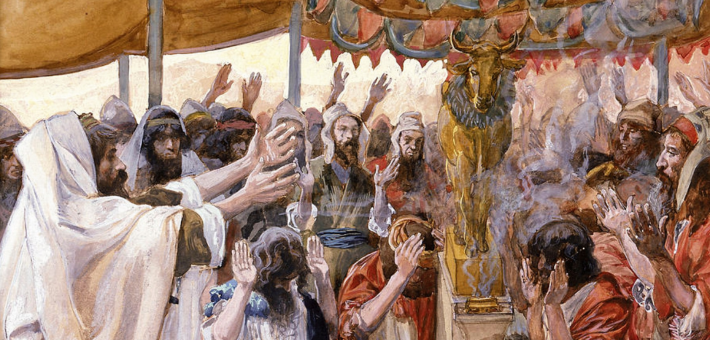

The people, tired of waiting for Moses to return from the mountain, ask Aaron to “make gods” to accompany them on their journey, and Aaron decides a young bull would be just the thing. Young bulls were symbols throughout the ancient Near East of strength, fertility, and divinity, and their images were frequently found in cultic contexts, including in Israel (King Jeroboam I is excoriated by the Deuteronomistic Historian for erecting statues of bulls at Dan and Bethel in the northern kingdom of Israel—see 1 Kings 12:25–30).

The people do not seem to be worshiping a different god, in that they assign the saving power of YHWH to the image (“These are your gods … who brought you up from the land of Egypt” [32:4]). Their disobedience is in violating the commandment against images (20:2), which was part of the covenant they had just affirmed (24:3, 7). Their raucous “festival” (there are sexual overtones in verse 6) is in stark contrast to the solemn meal celebrated when the covenant was appropriately ratified (24:11).

God’s response

God’s anger is arguably worse here than at any other moment recounted in Scripture, in that God is of a mind to end the covenant (just begun!) and destroy the people. Instead of continuing with this rebellious people, God will make of Moses “a great nation” (32:10), an echo of promises made to both Abraham and Hagar in Genesis.

Moses’ response

Moses implores God not to destroy the people, making two arguments:

1) God’s reputation will suffer in that liberating this people from slavery in order to immediately destroy them makes God look confused at best and incompetent at worst; and

2) Moses reminds God that God made promises to the ancestors, and to break those promises would violate God’s own character.

Moses is persuasive (32:14), with the result that the covenant will continue and, as the rest of Israel’s long history with God unfolds in Scripture, will never be broken by God despite the repeated ruptures of the covenant promises on the part of the people.

Final thoughts

The relationship between God and God’s people is at its lowest point in the whole Bible in this passage. The human propensity to renege on promises just made is evidenced throughout history—the Christian tradition acknowledges this in the emphasis on sin as a key aspect of the human condition. In the context of the 21st century, it is worth reflecting on the ways in which Christians are tempted to fall away from the hard work of waiting on God—the challenging, complex work of being faithful to God—when we are tired and feel we have been waiting too long.

Instead we are often eager to embrace the worship of something other than God under the name of the living God. Worshiping other gods under the name of the one true God is easy, offers immediate gratification, and feels superficially good (that festival was a heckuva party). This passage feels especially germane in these days when Christian nationalism is on the rise, and raises important and challenging questions for all of us about what faithfulness entails.

Notes

- Dennis T. Olson, “Exodus,” in Theological Biblical Commentary, ed. Gail R. O’Day and David R. Petersen (Louisville: Westminster John Knox, 2009).

- Ellen F. Davis, Opening Israel’s Scriptures (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019), 50–61.

PRAYER OF THE DAY

Faithful God of an unfaithful people,

The people of Israel doubted your power and turned to other gods to fulfill their needs. We too, turn to other gods, seeking acceptance, power, and independence. Show us how to live humbly in you, and walk in your ways, in the name of the one who offered true power to all humanity, Jesus Christ our Savior and Lord. Amen.

HYMNS

Lord of all nations, grant me grace ELW 716

Lord of all being, throned afar H82 419

My song is love unknown ELW 343, H82 458, NCH 222

CHORAL

Go down, Moses, David Cherwien (Sacred Music Press)

October 6, 2024